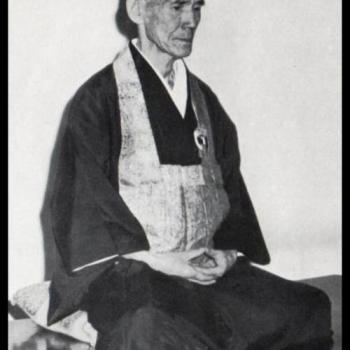

In my last post, Who Is This Hakuin Guy?, I gave some background for Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴, 1686 – 1768) and the record of his teachings, the recently published Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn: The Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku, translated by Norman Waddell. Like most radical reformulators of the buddhadharma (e.g., Nagarjuna, Bodhidharma, Huineng, Dōgen, etc.), Hakuin saw himself as holding true to the essence of the Zen way, rearticulating that essence, and innovating a method for its attainment. In this post, I want to give an overview of what Hakuin taught, especially about kenshō, hopefully holding it up as a mirror for our times.

By the way, kenshō (見性) means “seeing [true] nature or essence.”

Hakuin freely and refreshingly stresses the importance of kenshō. In his long verse, “78. Instructions to the Assembly at the Opening of a Lecture Meeting on the Lotus Sutra,” the primary source for this post, Hakuin begins with these two lines:

“Anyone who seeks to master the Buddha’s Way/Must begin by attaining a kenshō of total clarity.”

The importance of kenshō

James Myōun Ford Roshi puts it this way: “As I see it first and foremost Zen is about awakening.”

It’s fair to say that not all Zen folks agree about that primacy of kenshō. For example, in a recent exchange of views, another Zen priest and teacher from one of the large Sōtō centers described the attitude of his institution as “rabidly anti-kenshō.”

Now, synonyms for kenshō include awakening, enlightenment, and satori. And the “buddh” in Buddhism means “awake,” so we Buddhists might call ourselves “Awake-ists.” If only it rolled off the tongue….

In any case, and whatever it’s called, I find it really surprising that a Buddhist group would be rabidly anti it.

As is often the case, support for contemporary predilections of Sōtō practitioners is found in the words of the thirteenth century founder of the Sōtō lineage in Japan, Dōgen. Sure enough, he had an issue with the word “kenshō.” “Seeing into mind and seeing into essence,” he wrote in his “Mountain and Rivers Sutra,” “is the activity of people outside the way.”

What Dōgen seemed to be saying here is that if you think you have some experience that reveals “mind” or “essence” as a thing, you are off to see the wizard, skipping along the yellow brick road of delusion. Of course, our Zen way is about intimacy and identity action, or as he expressed it kōanically, “Green mountains are always walking.”

Fair enough.

Now, I’d like to note that when it comes to words, Dōgen was quite a nitpicker. He also didn’t like the word “Zen,” but we still use that word widely, so why not “kenshō?” I’m wondering if those that are rabidly anti-kenshō are against the word, as Dōgen was, or against what it represents – awakening – which Dōgen wasn’t.

For me, experiences of awakening have been central to my Zen process. And so I find Hakuin’s emphasis so clear, and, yes, supportive of my predilections. In my view, the word that we use to describe the experience is not so important. How about respectfully hearing Dōgen’s concern about the possible misuse of the word “kenshō” and then moving on?

Which is what I’d like to do in this post. Although, clearly, after forty years of Dōgen study, I’m finding that challenging! Still, I’ll keep working on it during this year of Wild Fox Zen blog Hakuin focus.

Back to Hakuin

His first line opening his lecture on the Lotus Sutra Hakuin says, “Anyone who seeks to master the Buddha’s Way,” has a couple significant points. First, this Way is wide open – “Anyone.” You don’t have to be a Zen marine, really smart, or really healthy in every way. The important first point is this: “Anyone.”

Second, Hakuin implicitly recognizes that there are a variety of motivations for practice, including health, well-being, favorable rebirth, and personal effectiveness. In other passages in the Complete Poison Blossoms, Hakuin affirms and works with these and many other motivations. But here Hakuin is talking to is those who want to master the Buddha Way, the process of awakening.

If you are so motivated to master the Buddha Way, then Hakuin argues that you “…must begin by attaining a kenshō of total clarity.” How could you be a master of awakening if you’ve not experienced an awakening? But it’s not just any awakening that Hakuin recommends but a “kenshō of total clarity.”

Kenshō experiences, abrupt embodiments of nonduality, come with a wide-variety of characteristics, including special effects that can confuse and distract us from the heart of the matter – the intimate knowledge of self-and-other – and obscure the clarity that we-and-the-world itself are at once lacking in any abiding substance, and we-and-the-world are one within the great play of interaction, interdependence, and interpenetration.

Finally, also implicit in this passage is Hakuin’s predilection that kenshō is the beginning of the Buddha Way, not the end. To “… think experiencing kenshō is enough,” he writes, is “… a great fraud.”

It’s also important to note that kenshō is a part of our human inheritance and is really quite common, therefore, it makes sense to position kenshō in the beginning of the life of practice. That said, however, not everyone who diligently practices experiences kenshō, at least not in the time frame that they prefer. This also is an important topic that I’m going to kick down the road to future posts.

In future posts, I’ll also address Hakuin’s view of how to realize kenshō. For now, I’ll just note that one of the great virtues of working with a kōan teacher, is that after kenshō, there is a brilliant system for culling, clarifying, and cultivating verification.

Post kenshō practice

Hakuin continues,

“When it is as clear as a fruit lying in your hand/Crack the secret ciphers of the Eastern Mountain”

So, “a fruit lying in your hand,” gives us a sense of how clear “clear” is. It’s really obvious. “How could I have missed that I have a mango in my hand? Amazing!”

Waddell notes that “Secret ciphers or ‘passwords’ (angō-rei) originally referred to secret passwords used by soldiers in wartime; here it means potent kōans, generally.”

And it’s quite nice that, in English, “cipher” also means “zero.” And so we have here a found kōan – “quickly, crack zero!”

“Eastern Mountain” is a specific reference that Hakuin seems to mean more generally, to paraphrase Waddell, as Zen utterances of marvellous efficacy. Hakuin lists eight kōans, secret ciphers, that are fitting for post-kenshō practice, including “Huang-lung planting vegetables by the zazen seat.” I’ll return to this kōan soon.

Then after you’ve passed through these post-kensho kōan, Hakuin encourages us to take up a couple sutras as secret ciphers, specifically the Lotus and Vimalakirti sutras. This is really creative! “I have always lamented Zen’s ignorance of the sutras,” writes Hakuin, “Monks plodding ahead aimlessly like blind donkeys.”

Hakuin continues, “Unless you grasp their meaning, even with kenshō/You will fall unawares into the abyss of emptiness.” And on the other hand, “And if you read the scriptures without having kenshō/You’re only a parrot imitating someone else’s speech.”

Again, realizing emptiness, another way of languaging kenshō, is just the first step. If we get stuck there, “squatting inside attainment,” we will be sick through and through. “Bodhisattvas of superior capacity,” Hakuin writes, “dwell in the dusty realm of differentiation, constantly carrying out their practice amid an infinite variety of distinctions.”

Vowing to share kenshō with others

And now we come to the heart of Hakuin’s contribution to our Zen way.

“I want you [people] to keep the ancients’ practice in mind,” says Hakuin in his Lotus Sutra introduction, “While spurring the vow-wheel on to save living beings.”

Hakuin came this realization at age forty-two while reading the Lotus Sutra’s chapter on “Skillful Means.” As Waddell notes it in Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, “In that chapter, the Buddha reveals to his disciple Shariputra the true nature of the Mahayana Bodhisattva, whose own enlightenment is but the first step in [their] career of assisting others to attain theirs.”

Cracking the secret ciphers of the ancients, and then repaying our great debt of gratitude by aiding others are equal, mutually reinforcing aspects of post-kenshō training. One of Hakuin’s outstanding contributions to our practice is the visceral way he connects the heart of the way, the altruistic vow to save all beings, beginning with our first steps on the path, resolving to realize kenshō, realizing kenshō, and then working through difficult-to-pass kōans in order to share awakening with others. Thus the Bodhisattva Vows, beginning with “Beings are numberless; I vow to free them,” are made incredibly concrete.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Tetsugan Sensei and Dōshō Rōshi.