In this final post of the series on the keyword method of Dàhuì, I begin with a connection to Shakyamuni, move to more detail on Dàhuì’s teaching, cite a parallel with Dōgen, include a modest proposal to modify the kōan curriculum to more directly address contemporary issues, and close with Old Man Bob. Here goes:

“Through the round of many births I roamed without reward, without rest, seeking the house-builder. Painful is birth again & again. House-builder, you’re seen! You will not build a house again. All your rafters broken, the ridge pole dismantled, immersed in dismantling, the mind has attained to the end of craving.” (1)

So the Buddha of the Pali Cannon described his definitive awakening and the great possibility for everyone for this very life. Devout, diligent practitioners for the last 2,600 years have aspired to taste the same mind as Buddha, breaking the ridge pole, the mind of dualism, of I-and-thou, of life-death. Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s translation has this nice post-awakening riff as well: “immersed in dismantling,” suggesting the ongoing cultivation of verification in our present Sōtō Zen lingo.

Since the Buddha immersed himself in dismantling, many innovative skillful means have been developed, responding to the time, place, people, and culture. Many of these skillful means have had this same end-point in mind – breaking the life-death mind. None of these skillful means have more influence on awakening practice today than the keyword method of Zen Master Dàhuì Pǔjué (1089–1163). In this post, I’ll unpack his admonition to break the rafters and dismantle the ridge pole.

First, though, I should say that this is the tenth of ten posts in this series, so I’ll now share the usual series introduction and disclaimer:

In the recent translation of The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pǔjué, translators Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe offer nine themes, motifs, that emerge in the letters about how to do keyword practice (話頭 huàtóu, Japanese, watō). I’ve been sharing them on the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training for students working with keywords (e.g., mu), and I’ll also be sharing them here for others who might be interested. Close study of an ancient text can help both students and teachers notice details of the method and refresh their practice spirit. If you are working with a keyword with another teacher, consult with them, of course, and rely on their guidance.

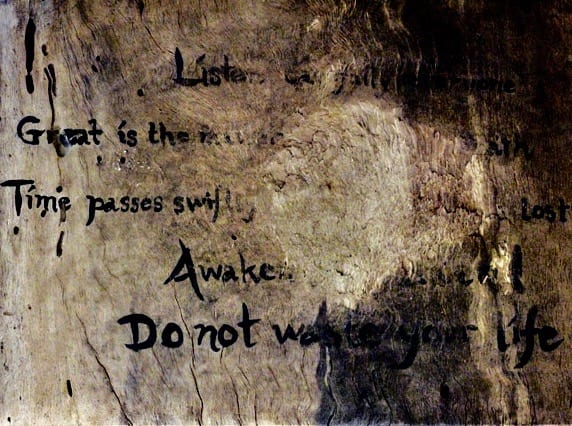

Theme 9: You must smash to smithereens the mind of life-death

Broughton and Watanabe: “The smashing of the mind of life-death (2) is the sine qua non of practice in Letters of Dàhuì. Sometimes Letters of Dàhuì phrases this theme as the smashing of uncertainty [aka, doubt] about the keyword:”

Letter #12.1: “If you want true stillness, what’s necessary is the smashing of the mind of life-death. Even without doing diligent practice—if the mind of life-death is smashed—stillness will come of its own accord. The stillness skillful means [i.e., the practice of sitting] spoken of by the earlier noble ones is solely for this. It’s just that, during this latter time, the party of mistaken teachers doesn’t understand the former noble ones’ [exhortations to sit] were skillful-means talk.” (3)

Comment

In the passage from “Letter 12,” quoted above, and throughout the Letters, Dàhuì embraces a modern educational strategy – focus on the outcome, test the processes of traditional pedagogical strategies that you believe will lead students to the desired outcome, and innovate as necessary. In such a view, even zazen is a skillful means, not the end itself. And despite the rhetoric of the Post-Meiji Sōtō Orthodoxy, there is considerable evidence that Dōgen also held the same view as Dàhuì, although you might be relieved to hear that is beyond the scope of this post. (4)

What is the desired outcome for those emulating the Buddha? The Buddha devoted himself to awakening, ongoing dismantling, and serving others in their awakening journey. What is awakening? For Dàhuì, breaking the mind of life-death. From shattering of the ridge pole and continuing through ongoing diligent practice, true stillness naturally flows. There is no inside/outside, and so the vast mind, verified by the ten thousand things, can rest in suchness. In this, Dàhuì has turned the buddhadharma upside-down. Instead of teaching that stillness leads to awakening, or that stillness is awakening, he taught that awakening leads to true stillness.

Dōgen also had something to say about emulating the Buddha and breaking the baskets and cages:

“The embodied buddha does not make a buddha; when ‘the baskets and cages’ are broken, a seated buddha does not interfere with making a buddha. At just such a time, from one thousand, from ten thousand ages past, we originally have the power ‘to enter into Buddha and enter into Måra.’ Stepping forward and back, its measure fully ‘fills the ditches and clogs the moats.'” (5)

“Enter into Buddha and enter into Måra,” expresses the heart of advanced Zen training – not only awakening, but (re)entering the wild world of death and desire (aka, Måra), to benefit living beings. The translator of this last passage, by the way, Carl Bielefeldt, notes that Dōgen here seems to be quoting and reapplying a statement of Dàhuì. In “The Arsenal of the Chan School of Chan Master Dàhuì Pǔjué” (Zongmen wuku), Dàhuì praises someone’s awakening by saying, “You can enter into Buddha,” yet he also sees their limits, “but you cannot enter into Mâra.”

Dōgen, using the words of old Dàhuì, is talking about that time that we can enter into both awakening and delusion. It’s hard to imagine a better time for that than right now.

Modifying the kōan curriculum to emphasize the baskets and cages of the current world

It is well known that many of the Zen master luminaries of mid 20th century Japan had broken the baskets and cages, passing through many thorns and barriers of their lineages, and yet came out of their training system with nationalism and sexism, at least, pretty firmly entrenched. That’s a problem.

In our present day, nationalism, human centrism, sexism, and classism still plague the world, and are still not specifically addressed in the kōan curriculum, except in the most general ways. For Americans, I’d add “American exceptionalism” to the list. For white Americans, I’d add white privilege too. And there are, I’m sure, local flavors around the world that could be addressed as well.

Is there a way to help people break through the mind of life-death and then attend to the ugly manifestations of dualism as identified above? Can it be done without making the kōan curriculum an exercise in left-leaning thought control?

I think so. And so the work continues.

https://youtu.be/wMDO_lvSQYE

(1) Shakyamuni Buddha, Dhammapada, “Jaravagga: Aging,” translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

(2) “Smashing the mind of samsara” (生死心破) could also be translated as “breaking life-death mind”

(3) The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pǔjué, “Introduction: Recurring Motifs in Huatou Practice,” trans. Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe. Modified.

(4) For more on this point in terms of Dōgen Zen, see What’s the “Just” in Just Sitting All About?

(5) Eihei Dōgen, Shobogenzo Zazenshin, trans., Carl Bielefeldt.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.