The theme here is the Cáodòng/Sōtō master Tiāntóng Rújìng’s (1163-1229, 天童如淨; Japanese, Tendō Nyojō) instructions for breakthrough with the mu kōan – and my interpretation of such. I’ll first present my translation of Rújìng’s brief, penetrating, and precise teaching, and then offer a line-by-line commentary. By sharing some context (like what is an “iron broom”?), I hope to add some depth to the mu field.

But my prayer is that this might inspire some readers to take up the mu kōan with a qualified Zen teacher (and one with very high standards).

Incidentally, this is another in my ongoing series on Zen ancestors before and after Dōgen that demonstrates that Zen is One School. In this post, I continue to focus on Rújìng, Dōgen’s teacher. Although Rújìng was in the Cáodòng/Sōtō lineage, and contrary to the story that’s perpetuated in most Sōtō circles today, Rújìng awakened with kōan and taught kōan introspection. There is utterly no trace of silent illumination in his work.

For those of you who are already working on the mu kōan with a qualified Zen teacher, my further prayer is that this might contribute to you breaking mu open. And, of course, if you find anything here to be at odds with instructions your qualified Zen teacher has offered to you, then follow their instructions.

And to those of you who’ve already broken through, how do you do?

Rújìng on how to break through the mu barrier

“When the divided mind flies away, how will you deal with it? Zhàozhōu little dog buddhanature mu. This single word mu – an iron broom. Where you sweep, confusion swirls around, swirling around confusion where you sweep. More turning, sweeping, turning. In the place you cannot sweep, do your utmost to sweep. Day and night, backbone straight, continuously without stopping. Bold and powerful, do not let up. Suddenly, sweeping breaks open the great empty sky. Ten thousand distinctions, a thousand differences exhausted – completely opening.”

Line-by-line comments

“When the divided mind flies away, how will you deal with it?”

Lost in the movement of time and mind, separating self and other, trapped in the swirl of conditioned thoughts, we let our lives run down the drain. Tick tock, tick tock…. What will you do?

“Zhàozhōu little dog buddhanature ‘mu.’”

These few words have led to more awakening experiences than any other. So if you are interested in such a thing, become such a person. Rújìng speaks here in an abbreviated manner for those who are inside the gate of Zen practice. I’ve presented it in English as close as I can to how it appears in the original (趙州狗子佛性無), i.e., without any articles, conjunctions, or embellishments.

Here is a fuller version of the kōan, still brief, but it unpacks Rújìng’s shorthand:

“A monk asked Zhàozhōu, ‘Even a little dog has the Buddha Nature, no?’ Zhōu said, ‘No’ (Japanese, ‘mu’).”

The monk is not another person. It is you are asking about you – one or two? And what is mu?

“This single word mu, an iron broom.”

From this little dog of a sentence, there are several important context points. To begin with, Rújìng’s “this single word mu” (只箇無字) sounds a lot like a keyword (話頭, huàtóu, Japanese, watō) expressed in different characters. The keyword method is generally attributed to the Línjì/Rinzai teacher Dàhuì Zōnggǎo, so I see this as clearly affirming the One Zen School approach of Rújìng. (1)

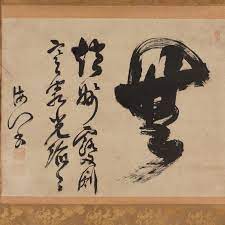

Second, it’s worth briefly noting the etymology for the mu character (無). The ancient bone form represented a person dancing, at first holding cattails, and then later the cattails were replaced with fire.

Finally, what is the “iron broom”? Rújìng may be using it here in two ways. First, “iron” is used as a metaphor for that which is indestructible and unified. Iron was the steel of the, well, Iron Age. “Playing the iron flute” is a similar metaphor.

Second, Rújìng might also have the “iron broom” in mind, an ancient Chinese martial art technique that involves sweeping the back leg around and cutting the legs out from under your opponent. (2) Although neither Rújìng nor I filmed this maneuver, this might give you the idea:

Both the iron broom and the dust wind up horizontal, at least for a moment. This is a key practice point – be the iron mu broom in dynamic activity while sitting, standing, walking, and lying down, sweeping out the legs from all seemingly separate phenomena. These complementary images – mu as dancing with fire and sweeping like an iron broom – point directly to the unified, embodied practice of mu that burns up and sweeps away separation.

“Where you sweep, confusion swirls around, swirling around confusion where you sweep.”

If you take up the mu kōan properly, it will disrupt the flow of linear time and the divided mind. That’s the point.

Rújìng uses the dynamic activity of sweeping to highlight how it happens that when a student first aims at becoming one with mu. Inevitably, the dust of the world, the many bits of confusion and separation, become vividly salient.

You might be inclined to just sit passively and let the dust settle, lingering in limp laxity and/or withering away in karmic goo. Such a strategy would be like dozing away in the passenger seat of a car driving south on Interstate 35, seeing the signs for Des Moines, Kansas City, and then even San Antonio, and all the while trusting that the car is headed north toward Duluth.

In other words, you’re in denial and going a long way in the wrong direction.

Rújìng’s instruction to be the iron broom, unifying bodymind, is to vigorously contact and upend every bit of dust. So if you’ve just been enjoying the ride, get in the driver’s seat, turn the damn car around, and throw yourself into being the iron mu broom.

“More turning, sweeping, turning.”

The important practice pointer here is to stay with the process of turning, sweeping, turning with all the dust, confusion, and separation. You simply must become the iron mu broom completely without a hair’s breadth of a gap.

“In the place you cannot sweep, do your utmost to sweep.”

It’s behind your back! It’s out of reach! It’s floating in the sunlight.

Enter Leonard Cohen:

“All busy in the sunlight

The flecks did float and dance,

And I was tumbled up with them

In formless circumstance.”

“Day and night, backbone straight, continuously without stopping. Bold and powerful, do not let up.”

You heard it. Throw yourself into the process and kick the dusty legs out of end-gaming, moaning and groaning about how long this is taking. Kiss it all with the indestructible iron mu broom.

But, hey, how long will it take?

It really depends on you (i.e., the power and focus of your intention, skill in absorption and inquiry, and application on and off the cushion), your relationship with your qualified Zen teacher, and mysterious karmic affinity. Although I’ve heard it said that breaking through mu normally takes three years, “normally” has no fixed bounds. “Three years” too has no fixed bounds.

Your lifestyle – living as a householder, or as a monastic, or in solo retreat – will definitely impact your opportunity to seamlessly sweep as the iron broom. For the vast majority of students who take up the mu koan today, householders, it is definitely possible to break through. Diligent practice in daily life is vital, of course, as well as doing as many days of sesshin and solo retreat as the circumstances of your householder life allow. Even a bit more.

However, while you’re speculating, reflecting, and lost in thought, you miss the opportunity to be the iron mu broom. And unification with mu is just the preliminary step to the vivid breaking open that this allows.

“Suddenly, sweeping breaks open the great empty sky.”

Ahhhhh.

“Ten thousand distinctions, a thousand differences exhausted – completely opening.”

After the sweeping breaks open, the self and things of the world are lived as one family – “completely opening.” What I’ve translated here “completely” (通) in a dharma context suggests “…the completely free and unhindered functional ability of a buddha or a bodhisattva.” (3)

“Completely opening,” then is Rújìng’s lofty ancient standard for passing through the mu barrier of the ancestors. He’s not talking about a little glimmer of an insight or an intimation here.

In conclusion,

May there be many (but even a few might do),

in this generation, who practice diligently enough

to break through mu

in order to greatly benefit living beings

and pass the luminous buddhadharma

to the next generation.

(1) See The Most Revered and Most Reviled Zen Master Ever for more on Dàhuì.

(2) From email and conversations with Walter Bera Sensei, based on his email and conversations with Mike Johnson.

(3) Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, Charles Muller, http://www.buddhism-dict.net/cgi-bin/xpr-ddb.pl?q=%E9%80%9A

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi at Patreon.