Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.

What you’ll find in this post

What you’ll find here is a deep dive into the life of Tetsu Gikai (Pervading Clarity Justice Mediator), the third ancestor in the Japanese Sōtō succession, not to glorify him, but as inspiration for your own practice now. Gikai has long been a powerful example for me because of the rough bumps he encountered … and how he passed through. If you think that if you realize definitive awakening that your troubles will be over, well, think again.

Gikai’s life didn’t turn out like he (nor Dōgen and Ejō) expected. And neither has mine and I bet yours hasn’t either. Yet, Gikai succeeded in ways that he (and they) probably never could have imagined. Gikai lived through his troubles, though, with incredible aplomb, and is now a common ancestor to all of modern Sōtō Zen.

But specifically what you’ll find here: first a freestyle telling of Gikai’s story, then a translation of Gikai’s biography that I don’t believe has previously appeared in English, and then notes to the translation.

May we all realize the Buddha Way together.

A freestyle telling of Gikai’s story

Gikai was born to a leading family and left home anyway, or maybe because of such, and sought the Way first with a wrong-way lineage, Daruma-Shu, and then a right-way lineage, Tendai. When he met Dōgen he knew that he’d found an old Buddha and so spent the rest of his life clarifying and expressing the Way through Sōtō Zen.

In his youth, Gikai was Dōgen’s golden boy. He had more energy and passion for the Way than anyone, and as tenzo could be seen charging up the mountainside through the snow with buckets of rice in order to serve the bodhisattvas their midday meal. And he would still sit zazen every night until dawn.

He heard Dōgen talk about spring colors and had an awakening, yet his rough enthusiasm still got in the way of meeting people as they were.

After Dōgen died, he ran the monastery for Ejō and then let go of himself completely, receiving Ejō’s thorough-going confirmation. Then to China and back, also so that he could support the monastery and deeply establish the authentic way.

Gikai then succeeded Ejō as Eiheiji’s abbot and found his own voice, his own style of practice, integrating some elements of Shingon with Dōgen’s Zen. But his peers would not follow him and so he stepped down from the position as Eiheiji’s abbot when only in his fifties, a monk with a lot of promise that he had failed to fulfill.

A broken monk, he took care of his mother and lived in a hermitage for twenty years – alone, cold, and friendless – until an old buddy from his Daruma-Shu days, now at Daijōji, called and asked him to lead a repurposed monastery. Then in a fresh space, he fully unfurled the Zen Way, passing the lamp of illumination to Jokin (and three others).

Jokin seized the day and eventually became identified with the style of practice that was Gikai’s creation. This was the very same style of practice that led to Gikai’s massive stumble from Eiheiji. It turned out to be exactly what Jokin employed to spread the buddhadharma widely throughout the land.

Nine bows to you, old man.

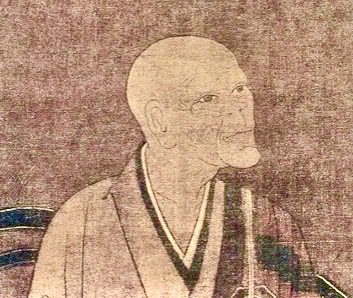

The Biography of Daijōji Gikai (1219-1309) (1)

The teacher’s posthumous name was Tetsu and his dharma name was Gikai. Etsu province was his home and Fujiwara was his clan name. He was a descendant of Great General [Toshihito], born the second day of the second month in the year of Jōkyū (1219). (2)

At thirteen he went to Hajakuji on Honshu. Venerable Ekan shaved his head. The next year he ascended the auspicious peak and received full ordination. He studied the Tendai teaching and surrendered to the responsibilities of receiving the precepts. He carefully studied and illuminated the Śūraṅgama Sûtra. (3)

At twenty-three, Gikai changed robes and practiced with the Venerable Dōgen at Kōshōji. He was dedicated and wholehearted. One day, Gen went up to the hall and said, “‘This dharma abides in a dharma position. Worldly appearances are permanent.’ Spring colors, hundreds of red flowers; high in the willow, a partridge calls.” (4)

The master heard this and awakened.

Gikai moved with Dōgen to Eiheiji and served as the head cook (tenzo) and next as the comptroller (kansu). Everyday he managed many issues for the assembly. Every night he sat zazen until dawn. Gen saw that he could apply his aspiration. He [Gen] always slapped his thigh and said, “A true dharma vessel! Someday he [Gikai] will certainly spread my dharma widely.” (5)

After Gen died, the great honorable Koun filled his seat and assigned the master [Gikai] to be head of the assembly. One day, the master hurried into the teacher’s small room (J. jōshitsu) and said, “Today somebody attained realization through the words of the prior master [Gen]’s ‘bodymind drop off.’”

Koun said, “What did you do to give birth to realization?”

The master said, “If I’m not mistaken, the barbarian’s beard is red. Still there is a red-bearded barbarian.” (6)

Koun approved of him and said, “You are in the place acquired by the prior master, realizing his nondiscursive intent, fully knowing the prior master’s great samadhi, hitting the mark. You personally experienced final enlightenment. Within the buddhadharma, this attainment is most difficult for humans. It seems that if a person avoids extinction, the buddha seed does not grow. Even though they become human, they’re not a vessel [for the buddhadharma]. Also inevitably, there is hardship. This is the issue that sages of the past have struggled with, and those in the present too must struggle with, that I now have obtained. You have already escaped this hardship. Today, then, you have died never again to regret. Who is it that is still alive?”

Tearfully, in this way, the living master [Gikai], bowed and withdrew. (7)

He finally hoped to cross the ocean and carve a wish-fulfilling wheel of empty space, vowing before an image of two great masters, saying, “If I go south, then I’ll return gloriously adorned.”

Thereupon in 1259 he went to Song China, wandering through the monasteries, visiting all the noted teachers, and receiving their appreciation. Then he returned home in 1262. Koun was extremely pleased, meeting him at the mountain gate. Prime Minister Hatano Shigemichi sought [Gikai’s] Zen counsel and offered his support. (8)

Then the master [Gikai] opened the hall, offered incense to Koun Ejō and succeeded him [as abbot]. He respectfully faced the assembly and publicly extinguished selfishness. Consequently, he distanced himself from the Way of the full moon, and administered the monastery for six years.

He then abdicated in order to care for his mother. He took up the style of Mùzhōu. Householders throughout the country and the emperor admired him. They formed a long line to invite the master [to leave his hermitage and lead another monastery]. (9)

Then the master had a night-time dream, where he tried to leave the mountain, but tangling vines coiled around his feet. He did his utmost to cut through them, but could not. After he woke up, he pondered this, and thought, “My ancestors do not permit me to go.”

Then his aspiration to leave declined, and he abandoned himself to leisure for twenty years. Hatano Shiro offered food and clothing, but the master did not accept. Alone, cold, austere, peerless, tasting the settled life while drifting with the clouds.

However, when receiving the dharma transmission robe at Eiheiji, handed down by his teacher, [he was told] “Do not allow this to be cut off.” Then the Venerable Chōkai of Daijōji, having received a large donation from the Fujiwara family, came and asked the esteemed old teacher [Gikai] about the dharma. He [Chōkai] then changed [Daijōji] to the Zen lineage, and asked the master to become the first generation teacher. The master accepted and became abbot, hung his dharma banner high, and opened the gate of the main hall wide. The various monasteries sent four tables of dana in appreciation for the old man’s great compassion, inspiring the assembly to cross the river. (10)

Later, following destiny, the eminent monk Keizan Jokin filled his seat. So after ten years, the master built a straw hut near the main monastery and closed the door, forgetting the ways of the world with his walking staff, rain hat, monk’s bundle – nothing more. (11)

On the twenty-fourth day of the eighth month, 1309, he showed sickness. On the second day of the ninth month he called a novice monk to shave his head. On the twelfth day an assembly gathered and he spoke at the main temple until the fourteenth day when he left the assembly.

This verse explains his teaching:

Seven stumbles, eight blunders – ninety-one years

Reed flowers covered with snow

From noon to night the moon is full

He then sat cross-legged for a moment and died, having enjoyed a long life of 91 years with 78 summer retreats. His disciples used his dharma platform to maintain [his teaching]. He gave dharma transmission to four people: [Keizan] Jōkin, Gi’in Shūen, Kaiki, Kakuzen Monfū.

Notes for those of the dharma geeky persuasion

(1) From Biographies of Soto Masters in Japan (日域洞上諸祖伝), trans, Dōshō Port. Tetsu Gikai is call Daijōji Gikai here because Daijōji was the name of his last monastery and Zen masters were often called by their place names (e.g., Eihei Dōgen).

For other resources about Gikai, see William M. Bodiford, Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, Chapter 5 Gikai: The Founder of Daijōji; Steven Heine, From Chinese Chan to Japanese Zen: A Remarkable Century of Transmission and Transformation; Richard Bryan McDaniels, Zen Masters of Japan: Second Step East, 67-69; and Heinrich Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History (Japan), 130-137.

(2) Like Dōgen, Ejō, and Daiō, Gikai was a member of a leading aristocratic clan, the Fujiwara, and although the clan had seen their influences waning, they were still one of the leading families in Japan. Especially after moving to the mountains, Dōgen’s group was dependent on the local feudal lords for support, which is noted above. In other words, Gikai and many of the early members of the Zen movement were socio-economically in the upper class and/or supported by the upper class.

(3) Ekan, like Ejō and many of Dōgen’s disciples, was a member of the Dharma-Shu. See The Luminous Koun Ejō Zenji: Background, Awakening, Legacy for more. “…Ascended the auspicious peak” refers to Gikai training at Mt. Hiei, the center of the Tendai school. He received full monastic ordination there, probably with the ten major and forty-eight minor bodhisattva precepts. Gikai was sent to Mt. Hiei by his teacher, Ekan, whose school, the Daruma-Shu has been frequently dismissed due in part to their disregard for the precepts. And yet here we have Ekan sending Gikai to receive the precepts – one of the many historical inconsistencies that are found in the record.

Gikai’s relationship with Ekan continued even after Dōgen took some members of the Daruma-Shu into his community, including Ekan, who then became a leading student of Dōgen, serving at Eiheiji as head monk. Gikai received Dharma-Shu transmission from Ekan, just before Ekan died, apparently with Dōgen’s blessing. Dōgen told Gikai that he regretted not giving Ekan transmission, saying that he just forgot to do it.

Later, Gikai passed Ekan’s Dharuma-Shu transmission to Keizan Jokin, where the line ended. Nevertheless, the embrace and prevalence of dual transmissions in the early generations of the Japanese Sōtō succession is certainly part of our inheritance.

(4) “Changing robes” was necessary because Dōgen brought the clothing style of 13th Century China with him when he returned to Japan. Apparently, Dōgen’s change of robes for monastics caused quite a stir.

“Gen” is used for Dōgen throughout this text after he is introduced. This common practice to refer to monks with the last character of their dharma names in classic Zen texts and still today in some Zen communities.

The phrase, “This dharma abides in a dharma position. Worldly appearances are permanent,” quoted by Dōgen is from the Lotus Sutra, Chapter 2: Skillful Means. A similar poetic capping phrase by Dōgen can be found in Dōgen’s Extensive Record, 91.

(5) Referenced here is Dōgen’s mysterious move from near Kyōto to Echizen in the late summer of 1243 and what became Eiheiji. Gikai’s connections to the area, as well as Ejō’s, may well have led to the move. In fact, Ekan’s former monastery, Hajakuji, was located nearby, close enough for monastics to move back-and-forth. Gikai frequently visited Hajakuji while training with Dōgen.

Before Eiheiji was constructed, Dōgen’s small band of monks stayed on Mt. Zenjiho in an old temple building that lacked a kitchen. Gikai served as tenzo and cooked meals at a farm house about a mile down the mountain. He would haul up food along a steep mountain path twice each day. Shohaku Okumura Rōshi reports visiting both sites and that it took about an hour of intense climbing to go from the farm house to the area where Dōgen’s monks stayed. Although the reason for their departure from the Kyoto area is unknown, and the cause of much speculation, they appear to have abandoned a functioning monastery complex and moved into emergency quarters without advance planning, much like they were hiding from the mob.

Despite Gikai’s years of extraordinary service to Dōgen and the sangha, as well as his awakening experience with Dōgen, he did not receive dharma transmission from Dōgen. Nor, for that matter, did Jakuen who had followed Dōgen back from China, and Ekan, mentioned above, who had been an abbot of a Daruma-Shu temple, Hajakuji, and then became a student of Dōgen, bringing at least several students with him, including Gikai.

Clearly, Dōgen had a standard for dharma transmission beyond initial awakening and extraordinary service. Dōgen told Gikai that he needed to work on grandmotherly heart, the mind of kindness toward all living beings. Gikai reported, “I have not forgotten the admonishment that I did not have a grandmotherly heart. However, I don’t know why Dōgen said this.”

In Dōgen’s final instructions to Gikai, he also told him to stay at Eiheiji and that if he, Dōgen, recovered from his illness, then he would give Gikai transmission.

(6) It seems that Gikai was using Rújìng and Dōgen’s expression, “bodymind drop off,” as a kōan. Gikai’s response plays with the Wild Fox kōan. After Huangbo slapped Bǎizhàng, he clapped his hands and laughed, saying, ”You got me! The Barbarian had a red beard, and here’s a red bearded barbarian.”

Thomas Cleary in Timeless Spring, translating a different text, Eihei kaisan goyuigon kiroku (Record of the Final Words of the Founder of Eiheiji), has a somewhat different version of this encounter and the aftermath:

“Later, when Ejo inherited the seat at Eihei, the master Gikai assisted him. One day when he went to the abbot’s room, Ejo asked, ‘How do you understand the shedding of body and mind?’ Gikai said, ‘I knew barbarians had red beards, here is another red bearded barbarian.’ Ejo agreed with him. Subsequently Ejo used differentiating stories of the past and present to refine him thoroughly. After a long time at this he obtained the dharma.”

(7) Notable here, compared to the above version of Ejō’s response, is that here Ejō offers a thorough verification of Gikai’s attainment. He also highlights the significance of the journey and describes the path for final awakening. Wow! And with his last sentence, “Who is it that is still alive?” assigns Gikai a life kōan.

(8) When Dōgen died, the construction of Eiheiji had not yet been completed. Ejō had not been to China and so didn’t know first-hand how the various buildings were to be used. So one of the reasons for Gikai’s pilgrimage was to study the architecture and functioning of the Chinese monasteries on which Eiheiji was modelled. It is reported that during his trip, Gikai was constanting sketching what he saw.

One quirk in this narrative is that a Chinese monk, Jakuen, who had returned from China with Dōgen and followed him throughout his career, stayed at Eiheiji for eight years after Dōgen’s death. So it seems that his expertise could have been used rather than Gikai going to China, a trip with a 50% rate of mortality. In any case, when Gikai returned, his promotion to abbot was supported by the main benefactors of Eiheiji, the Hatano family.

The images of the “two great masters” Gikai prayed before is unclear, but probably Dōgen and Ekan. Ejō could have been the second master, although as he was still living, it seems more likely to have been Ekan. Also, given that one of the main points in the criticism of the Daruma-Shu was that no one in the lineage (including Nonin, Kakuin, and Ekan) had been to China, Gikai was putting this lineage issue to rest.

(9) Mùzhōu was a successor of Huángbò who, after completing his training, retired to care for his mother. Mùzhōu also made straw sandals and hung them in trees near pilgrimage routes to support practitioners on the Way.

Historians are unsure about why Gikai stepped down as abbot of Eiheiji, but there was probably more to it than wanting to care for his mother and weave straw sandals, especially since Dōgen had told Gikai to stay at Eiheiji, and it appears that both Dōgen and Ejō had groomed Gikai for leadership. Some scholars speculate that during Gikai’s trip to China, and perhaps due to his natural proclivities, he developed a style somewhat different than Dōgen, adding some esoteric elements, and essentially increasing the focus on liturgy. Perhaps it was his lack of grandmotherly kindness, the issue Dōgen had identified, that led the old Eiheiji guard to reject him and his new teaching emphasis. In any case, it can be very difficult to move from being a peer to being the master.

(10) Daijōji had been a Shingon temple before Gikai’s abbotship. This foreshadowed a common development – Sōtō masters taking over Shingon temples in the country-side and converting them into Sōtō monasteries. It is also notable that the text cites where the financial support came from, this time from the Fujiwara clan.

(11) Keizan not only filled Gikai’s seat at Daijōji, but seems to have adopted his style. And, although it had been rejected by Eiheiji monks, it was this very style that was one powerful element in the overwhelming success of Sōtō Zen through the medieval period.

Steven Heine observes that “The key to Keizan’s success was a syncretic approach combining Chinese views of temple life, based on practicing meditation while giving public lectures (an approach he learned about from his teacher Gikai, who went to the mainland in the company of Daiō to study continental practice), with indigenous Japanese rituals that incorporated esoteric Buddhist and Shinto beliefs. This unique mixture of austere Zen training and the worship of local gods through native rites greatly contributed to the phenomenal popularity the Sōtō sect enjoyed in medieval Japan outside of the capital.” (141)

Bodiford (87) estimates that during the period between 1450 and 1650, on average, forty-three new Sōtō temples were built or converted from existing temples each year. That in a nation of about 25 million people. Current US population is about 13 times that. We would have to see about 550 new Sōtō temples each year for 200 years to match that extraordinary rate of growth.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.