Big life event – retired in early June from a thirty-some year education career (except for a few stints of full time Zen, I’d been at it since I was 22) and headed here to Portland, ME, to start a Zen training center, Great Tides Zen (oh, and please sign up for our newsletter updates in the bottom right sidebar).

Big life event – retired in early June from a thirty-some year education career (except for a few stints of full time Zen, I’d been at it since I was 22) and headed here to Portland, ME, to start a Zen training center, Great Tides Zen (oh, and please sign up for our newsletter updates in the bottom right sidebar).

Our apartment wasn’t going to be available until July 1, so we drove from Minnesota to Maine at a leisurely pace. I took the opportunity to listen to a half dozen or so dharma podcasts by as many teachers.

It’s really quite wonderful how available the dharma is these days and I enjoyed much of what I heard. There is a similar flavor to a lot of it, a distinctive and emergent American Zen, characterized by a fuzzy emotional tenderness. Quite lovely. If that’s what you’re looking for.

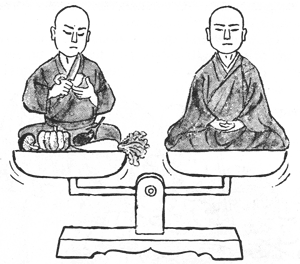

I chose podcasts that were about one of my long-time favorite subjects for inquiry – what is shikantaza? Shikantaza is also known as “earnest vivid sitting” and is misknown, I argue, as “just sitting.”

“Just sitting” has come to suggest a fuzzy, spacing-out, lulling vacancy that is not the way.

I began this inquiry in 1984 with all the energy of a youngster when Katagiri Roshi gave a series of talks extending over several years on Dogen’s Zazenshin or The Healing Point of Zazen, as I render it now. Of all of Dogen’s writings, it is this fascicle that most thoroughly unpacks the nature of what he elsewhere refers to as the wondrous (or mysterious) method of buddhas and ancestors – shikantaza.

Zazenshin is sometimes translated as The Lancet of Zazen which is okay. The “shin” in Zazenshin is also the character used for the acupuncture needle – thus, “healing point.” But perhaps “dynamic balance point” would also work.

In any case, I’ve been at this inquiry for 30 years, doing zazen, studying, traveling to do sesshin, monastic practice, koan introspection, etc., all in the service of this inquiry.

In Dogen’s dharma milieu, the two most common expressions for practice had been Silent Illumination and Key-Word Koan Introspection. Dogen coined the term shikantaza specifically for the essential method of buddhas and ancestors, going beyond these expressions. One important point here is that Dogen didn’t see himself making up a new practice, simply finding a new and more accurate expression for what all buddhas and ancestors have always practiced.

Dogen, a successor in the Soto line associated with the Silent Illumination expression, doesn’t use the phrase a single time in all his voluminous writings. That’d be like a successor in Suzuki San Francisco Zen not saying “beginner’s mind” ever in 2000 pages of dharma talks. Clearly, there must be some meaning.

In my view, a key point of Dogen’s Zen is to present a clear and lively integration of the Silent Illumination and Koan Introspection branches of the buddhadharma. He does this in part with the single word shikantaza.

Listening to the above-mentioned dharma talks, I noticed that what is called shikantaza in contemporary discourse bares little resemblance to Dogen’s shikantaza. It has become a catch-all term that includes things like bare attention, receptive awareness, panoramic awareness, mindfulness of mind, following the breath, and themeless meditation.

Another view has it that shikantaza is a mindfulness of body practice and regards the pose itself as sacred and drifts into cargo-cult (as John Tarrant has said) or fetish attitudes about it.

I’ve come to look at the difference this way – there is meditation practice in contemporary American Zen that is called shikantaza. Then there is the shikantaza that Dogen points to. They really don’t have much relationship.

I suspect that the Rev. Big-Mac Wrappers who go on about shikantaza as a method for vacant lulling, approach it as a belief system.

Why does it matter?

It matters because what we’re talking about here is the essence of practicing enlightenment and the above listed techniques are mostly forms of congealing in tranquility.

So what is shikantaza?

Dogen says repeatedly that “…it is the realization of the kôan.”

He goes on, “The ‘healing point’ in the Healing Point of Zazen is ‘the manifestation of the great function’, ‘the comportment beyond sight and sound;’ it is ‘the juncture before your parents were born.’ It is ‘you had better not slander the buddhas and ancestors;’ ‘you do not avoid destroying your body and losing your life;’ it is ‘a head of three feet and neck of two inches.’”

Yes, the old dog kindly and uncompromisingly gives us a nod toward the many faces of shikantaza as the presentation of the koan.

In our post-Hakuin world, I’d add this – shikantaza is the sound of one hand.

What can you do to begin the inquiry? I’d say that for most people, it might be necessary to do koan introspection (with someone who is clear and insists on clarity and doesn’t wantonly pass students through the system) to discover shikantaza.

Short of that (or in conjunction with that), “sit down, shut up, and pay attention” (as James Ford summarizes the path), is very sound advise.

So here in Portland, ME, we’ll soon begin again the work of this ongoing inquiry.