Celebrating Passover can be tricky for us awkward Jews.

Liberation and freedom have become the ‘Passover Problematic’ for the in-house critics of Judaism in the 21st century.

I’m thinking of Jews like me (growing in number each year) who insist that Zionism as the route to Jewish self-determination has turned out to be a bitter disappointment.

Jews like me who think our movement of political nationalism has created nothing but salt water because it comes at the expense of another people’s freedom.

Jews like me who think our synagogue ethics are as thin as a piece of matzoh because they insist that supporting all things Israel is a sacred duty.

Each year our liturgy calls us to welcome ‘the stranger’ to join our feast because all must enjoy this festival of freedom. Towards the end of the evening, we wait expectantly for the prophet Elijah, hoping his arrival will herald messianic times with justice and peace for all. We even pour him a goblet of wine.

But there’s no space at the table for the elephant in the room.

It’s an elephant draped in a giant black and white kaffiyeh, who rightly mocks our piety and our celebrations. It’s the same elephant that’s been turning up at our Yom Kippur services, our annual day of atonement, for decades but finds himself just too big to squeeze through the Shul doors.

So what’s to be done?

Let me introduce to you the Wicked Son of Seder night tradition. He has a radical solution to the awkward Jews’ Passover dilemma.

The Wicked Son

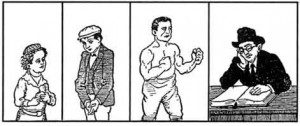

Our Seder night service, the Haggadah, tells us of ‘Four sons’ who draw out from their father the meaning of Passover and indeed Jewish identity.

First there’s the Wise son who’s keen to know all the details of the ritual celebration. The father looks proudly at him knowing that one day this child will lead a Seder night of his own. He tells him a few of the necessary do’s and don’ts of the ritual.

Then comes the Wicked son. Some Haggadot describe him as ‘Evil’. More modern editions of the liturgy soften the scorn by calling him ‘Rebellious’.

Third is the Simple son who just wants to know the basic story. The father replies patiently quoting a verse from the book of Exodus: “With a strong hand the Almighty led us out from Egypt, from the house of bondage.”

Finally there’s the Young son not old enough to articulate a question. The father looks down at him kindly and quotes another verse, “It is because of what the Almighty did for me when I left Egypt.”

Personally, whatever the label, I like the Wicked son more and more. He’s the smartest of the the bunch and on an evening designed to encourage questions, he asks exactly the right one.

And by the way, the Wicked/Evil/Rebellious son is just as likely to be a daughter.

Asking the right question

And what does this Wicked son say to their father?

The rebel looks his father in the eye and says: “What is this service to you?”. At which point the father explodes in rage.

What sounded like a perfectly reasonable question turns out to be a licence for the father to cast his child out of the family because, in the words of the Haggadah, the Wicked child has “divorced” himself from the community by “denying our very essence”. His father is told to “blunt the bite” of his child and explain to him that his attitude would have left him a slave in Egypt.

So what just happened? Why was the question so terrible to ask? And why do I think the Wicked son does us such a big favour?

Being ‘there’ or being ‘here’

The explanation can be found in the rabbinical instruction that at our Passover Seder night we must think of ourselves, and not just our ancient ancestors, as being personally rescued from slavery by the Almighty.

All of us, every one, in every generation, follow Moses and walk through the parted waters of the Red Sea with our feet left dry. When Pharaoh and his army come racing in their chariots, they are after ‘us’ and not just ‘them’.

The sin of the Wicked son is in formulating his question as “What is this service to you?” rather than “What is this service to us?”.

But what exactly is this service to his father, his mother, his siblings and all the rest gathered around the table? Has the Wicked son missed the point or spotted the problem?

Well here’s my awkward Jews’ commentary on the commentary.

In challenging the rabbinic instruction to ‘be there’ the Wicked child has identified the ‘Passover Problematic’ and offered Elijah’s cup of wine to the elephant with the keffiyeh.

If we are forever ‘there’ then we are forever the oppressed, forever the victim of injustice, forever racing to escape Pharoah’s chariots. Our Jewish view of the world is enslaved to the tribal past and deaf and blind to the tribal present.

By his ‘offensive’ question, the Wicked son is demanding that we open our hearts and minds to the present and apply our Jewish paradigm of freedom and liberation to the here and now. But there is a price to pay if we have the courage to be truly ‘here’. ‘Here’ we’ll discover that we’re no longer the oppressed but the oppressor. And the Pharaoh that has risen up in our own generation turns out to be ourselves.

A Wicked Passover

The Wicked son knows full well that criticism of Israel is not the latest mutation of antisemitism as some who should know better insist on telling us. That’s the opinion of those determined to be only, and forever, ‘there’.

‘Here’, Palestinian oppression is real. The anger is justified. The hatred is not irrational. What may feel like antisemitism turns out to be something worse. We have taken away the freedom of another people. And we have abandoned the post-Exodus mission to build a just society. We have “divorced” ourselves from our own tradition, we are “denying our very essence”.

So it’s tough celebrating a Wicked Passover.

The father needs to be challenged.The Seder night table needs overturning. The traditional Haggadah needs ‘occupying’.

Yes, there are modern peace and justice Passover supplements we can read. And radical third night Seders we can attend. But is that sufficient to address the most important Jewish issue of our time? The issue corroding our identity and our religion.

Perhaps celebrating Passover in our time has become an impossibility. The Afikomen, the broken middle matzoh, is so well hidden that it cannot be found.

Should the Wicked Passover be a silent gathering? A prayer without words? Elijah’s cup left empty?

And then us awkward Jews can return to the news channels, the marches, the letter writing and blogging to search for the broken matzoh that must be ‘here’ and not ‘there’.