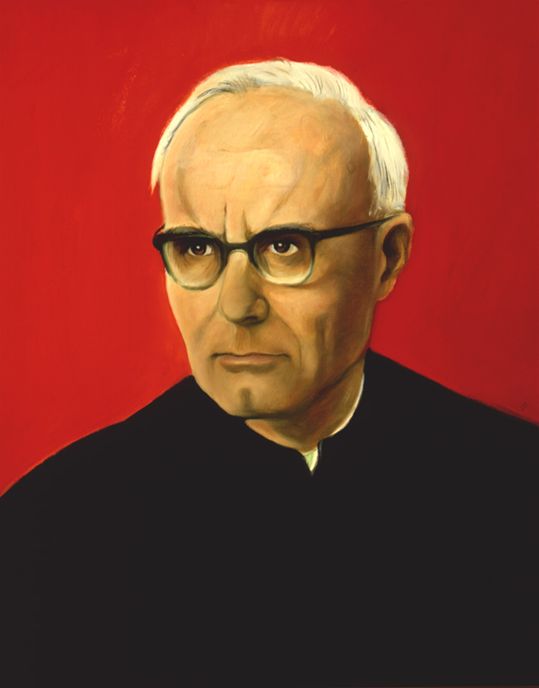

The thoughts I share with you now were originally published in 1961, and in English in 1963. Yet today, to this humble reader at least, they seem prophetic. Taken from the first chapter of the first volume of the title you see below, Fr. Karl Rahner, SJ, explains why in the Post Christian world of today, opting for the ghettoization of the Church is a non-starter.

Instead, he argues we should embrace the fact that we are a disapora people, because frankly, we have always been called to be so. For as the cross was Our Lord’s “sign of contradiction,” so too is the Church called to be the same, as it was in the beginning, briefly ceased to be in the Middle Ages, and is now again resuming this holy, and necessary, calling. “Take up your cross, and follow me.”

As I’ve mentioned before, we are called to be salt, light, and yeast. We are not called to be the new pharisees of the Catholic Ghetto. Fr. Karl helps me to see why below. My comments are in bold italics.

from Mission and Grace: A Theological Interpretation of the Position of Christians in the Modern World

My thesis is thus: Insofar as our outlook is really based on today, and looking towards tomorrow, the present situation of Christians can be characterized as that of a diaspora, and this signifies in terms of the history of salvation, a “must”, from which we may draw conclusions about our behavior as Christians…

How about a quickie refresher on the definition of diaspora? Go with 2) a & b here.

What, after all, does a person do if he sees the diaspora situation coming and thinks of it as something which simply and absolutely must not be? He makes himself a closed circle, an artificial situation inside which looks as if the inward and outward diaspora isn’t one; he makes a ghetto. This, I think, is the theological starting point for an approach to the ghetto idea.

The old Jewish ghetto was the natural expression of an idea, such that Orthodox Judaism was ultimately bound to produce it within itself; the idea, namely, of being the one and only Chosen People, wholly autonomous, as of right, in every respect, including secular matters, and of all other nations as not only not belonging in practice to this earthly, social community of the elect and saved, but as not in any sense called to it, not an object towards which there is a missionary duty.

But we are called to be missionary people. To be ambassadors for Christ, as a well known, inspired writer exhorts us to be. Fr. Karl makes it clear here,

But a Christian cannot regard his Church as autonomous in secular, cultural, and social matters; his Church is not a theocracy in worldly affairs; nor can he look upon non-Christians as not called; nor can he with inopportune and inordinate means aim to get rid of the “must” with which the history of salvation presents him, namely, that there are now non-Christians in amongst the Christians or real Christians in amongst the non-Christians. His life has to be open to the non-Christians.

Hmmm. There’s that word “theocracy” again. Not a good idea. Fr. Karl explains why,

If he encapsulates himself in a ghetto, whether in order to defend himself, or to leave the world to judgement of wrath as the fate which it deserves, or with the feeling that it has nothing of any value or importance to offer him anyway, he is falling back into the Old Testament. But this is our temptation, this ghetto idea. For a certain type of deeply convinced, rather tense, militant Catholic at a fairly low (petty-bourgeois) cultural level, the idea of entrenching oneself in a ghetto is rather alluring; it is even religiously alluring: it looks like seeking only the Kingdom of God.

Nice trick, that. Jon Stewart, of the very secular Comedy Channel news spoof “the Daily Show,” recently shared some words (language alert!) about how strident tactics wind up backfiring. Roll clip.

Now back to Fr. Karl, with my editing and emphasis.

Here we are, all together, and we can behave as though there were nothing in the world but Christians. The ghetto policy consists in thinking of the Church not only as the autonomous community of salvation (which she is) but as an autonomous society in every field. So a Christian has to consider [a Catholic poet being] greater than Goethe, and have no opinion of any magazine except [Catholic magazines]; any statesman who makes his Easter duties is a great statesman, any other is automatically a bit suspect; Christian-Democratic parties are always right, Socialists always wrong, and what a pity there isn’t a Catholic party.

The insistence, for the sake of the ghetto, on integrating everything into an ecclesiastical framework naturally means that the clergy have to be in control of everything. This results in anti-clerical feeling, which is not always an effect of malice and hatred for God. The interior structure of the ghetto conforms, inevitably, to the style of that period which it is, in make-believe, preserving; its human types are those sociological, intellectual, and cultural types which belong to the period and feel comfortable in the ghetto; in our case, the petty-bourgeois, in contrast to the worker of today, or the man of tomorrows atomic age.

It is no wonder, then, if people outside identify Christianity with the ghetto, and have no desire to get inside it; it is the sheer grace of God if anyone ever manages to recognize the Church as the house of God, all cluttered up as she is with pseudo-Gothic décor, and other kinds of reactionary petty-bourgeois stuff.

You can say that again! How, then, do we get beyond this “ghetto” mindset while not falling into the error of relativism?

We may be preserved from this danger, which has become a reality only too often during the last few centuries, by a clear-sighted and courageous recognition of the fact that the diaspora situation of [the Church] is a “must” in the history of salvation, with which it is right to come to terms in many aspects of our practical conduct.

You know, Christ never promised us a rose garden. Those “two greatest commandments” need to be not just pondered, but applied. All the while keeping these thoughts in mind,

Mankind is at its best when it is most free. This will be clear if we grasp the principle of liberty. We must recall that the basic principle is freedom of choice, which saying many have on their lips but few in their minds. —Dante Alighieri

The Catholic Church must be a clear beacon of hope, and a contrarian “choice” for the world today. I believe she is, otherwise I wouldn’t have bothered to become Catholic.

Update: Music for Mondays selections inspired by this post.

Update II: I couldn’t have said this better myself.