I have to admit to you, dear reader, that I am ignorant about much regarding the way “things” are. The world is a very complex place, and this is mostly through our own, dare I say it, grievous faults. And I also need to let you know that the semi-annual fracus in the Holy Places, like the one I shared with you yesterday, both sadden me and excite my interest in learning how they came about.

‘Tis true that trying in vain to flee from the chains of human history, one cannot forgot that history is also His Story. Curiosity killed the cat, and that fight in the Church of the Nativity killed what little sympathy I ever had for Orthodox Christianity’s claims to being one, holy, and apostolic.

If you ever wondered if I ever personally considered being Orthodox, what with my digging the Desert Fathers, and the Way of the Pilgrim and all, the answer is a resounding no. And it’s not because of the fisticuffs and brooms being thrown about in the Holy Places, but because the Orthodox broke away from Rome, early, and often. As I was searching for the True Church, see, I wasn’t about to go following the guys who tossed the See of Peter overboard. Besides, I learned there are Eastern Churches that are still faithful to Rome, so if I ever felt the “call of the East,” there is a Catholic way to explore that route.

And so I’ve gone off to read about the history of the Holy Places in an effort to try and grasp why “things” are the way they are over there. I probably won’t be back until after New Years. Of course, my learning about the situation there won’t change anything one iota. But you are welcome to join me if you like.

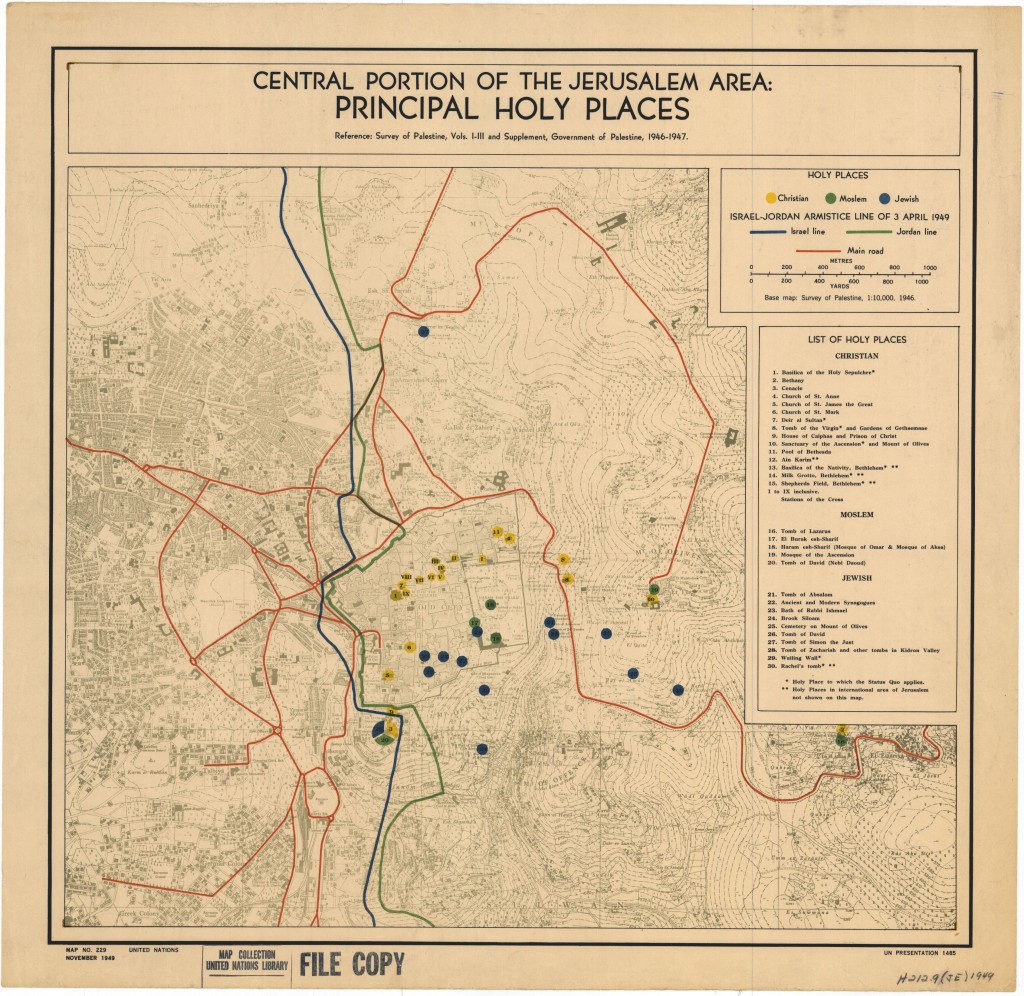

I found the memorandum written in 1929 by L.G.A. Cust, entitled The Status Quo in the Holy Places, and I’ll get you started on it below. Cust had been the British District Officer stationed in Jerusalem when the British Mandate took effect in 1920. This came about when the League of Nations transferred the area of Palestine out of the hands of the Ottoman Empire and brought it under the control of the British Crown. Later, in 1948, the state of Israel declared it’s independence when the Briitish ended their mandate on 14 May, 1948.

I understand that even to this day, this memorandum is referred to constantly by all of the parties involved in administering the Holy Places. Fascinating reading is coming your way.

THE STATUS QUO. ITS ORIGIN AND HISTORY TILL THE PRESENT TIME.

To form a just appreciation of what is signified by the Status Quo in the Holy Places and thus arrive at a clear understanding of the various rights and privileges that arise from it, it is necessary to trace the development of the Church from its earliest days. For in all its salient features the Status Quo is the logical outcome of some occurrence in history, until gradually the present complicated network of rights and privileges is produced.

It is natural that the actual scenes connected with the Life on earth of Our Lord must from earliest times have been of surpassing interest to His followers, and there has been no important event connected with the history of the Church that has not had its repercussion in the Holy Places.

A fundamental reason for the present state of affairs is the fact that, except for limited periods, the Holy Places were for 13 centuries under the dominion of a non-Christian power from whom concessions were obtainable by diplomatic pressure or other influences. A remarkable feature, however, of the Moslem domination is the tolerance displayed on all but very rare occasions towards the Christians. The barbarian invaders of Syria and Palestine, such as the Persians and the Charismians spread widespread destruction, and the mad Caliph al-Hakem destroyed with scientific thoroughness the second Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but the original Arab invaders and the Saracens later acted in the spirit of protectors rather than conquerors. This magnanimous attitude was doubtless encouraged in some degree by the fact that the Holy Places, and the contentions of the different Christian sects on their account, were profitable sources of income, but in Moslem eyes the Christians (like the Jews) are Kitabis, i.e. People of the Book, worshippers of the true God, but not in the right way, and whom the Prophet ordained should not be persecuted.

In strong contrast is the rivalry of the Christian Churches and Powers. The history of the Holy Places is one long story of bitter animosities and contentions, in which outside influences take part in an increasing degree, until the scenes of Our Lord’s life on earth become a political shuttlecock, and eventually the cause of international conflict. If the Holy Places and the rights pertaining thereto are an ” expression of men’s feelings about Him whose story hallowed those sites,” they are also an index of the corruptions and intrigues of despots and chancelleries during eight hundred years. The logical results have been the spirit of distrust and suspicion, and the attitude of intractability in all matters, even if only of the most trivial importance, concerning the Holy Places.

A. Early Period.

In the earliest days the Church was one and undivided. Administratively it was split up into three great Patriarchates : Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria. Jerusalem, under its Roman name of Aelia Capitolina, was a bishopric in the Patriarchate of Antioch depending on the Metropolis of Caesarea, at that time the administrative centre as well. Such was the position when Constantine founded the great Churches of the Anastasis and the Nativity.

By the Edict of Milan in A.D. 313, Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire, and the body politic of the Church set about organising itself. Seven great Councils were held, all of which were fraught with matters of great import for the future history of the Church.

At the Council of Nicaea we find the Bishop of the Holy City, who had already obtained a form of honorary primacy, being accorded ” the succession of honour.” At the First Council of Constantinople, the newly elevated Capital of the Empire was created a fourth Patriarchate. At the Council of Ephesus, Bishop Juvenal of Jerusalem attempted to obtain like privileges; he failed then, but succeeded a little later at Chalcedon, and so Jerusalem became the fifth Patriarchate. The venerable antiquity of the Jerusalem Patriarchate is therefore apparent.

These Councils, however, produced the heresies to which the lesser Eastern Churches trace their origin. After the Council of Ephesus the heresy of Nestorius broke off a large portion of the Patriarchate of Antioch, and the Council of Chalcedon saw the rise of Mono-physism, and the separatist Churches of this communion, the Armenian, Coptic, Syrian Jacobite, and Abyssinian.

I told you it was fascinating! Follow along with me on a journey into the past.