There has been a stir in recent days around the Presbyterian Church in America’s latest General Assembly, where two new overtures were passed to address the fraught issue of homosexuality and the pastorate. Overture 23 amends the constitution to state that in addition to practicing homosexuality, the use of “identity language” such as “gay Christian,” “homosexual Christian,” or “same-sex attracted Christian” can bar a man from ministry. This leaves it up to individual presbyteries’ discretion whether this can bar men simply for experiencing the temptation. Opposing voices like Greg Johnson, lead pastor of Memorial Presbyterian Church in St. Louis, argued that this was unacceptable and “hostile” to “gay people who want to follow Jesus in celibacy.”

For several years, Johnson’s church has hosted the controversial “Revoice” conference, pitched as a “safe space” for self-identified “gay Christians.” While speakers haven’t affirmed gay sex acts, some of them affirm virtually everything else about gay identity short of the actual sex acts. (See for instance, Grant Hartley’s 2018 and 2019 presentations on the “queer treasure” to be found in gay subculture.)

However, Johnson and other leaders portray themselves as a faithful remnant, preserving the traditional sexual ethic while pointing a better way for the church today to “walk alongside” Christians with same-sex attraction. Further, as Johnson explains in a recent podcast with Preston Sprinkle, plugging a forthcoming book, they see themselves not as upstarts but as throwbacks to Christian voices who “got it right” in the past before the rise of the ex-gay movement. One such voice, they claim, is C. S. Lewis.

Readers passingly familiar with Lewis’s work might be casting about right now for what they could possibly be referring to, since homosexuality was hardly a subject he treated frequently. In fact, there are a few key “Lewisian proof-texts” that regularly crop up in these contexts. What follows is my best attempt, based on all available evidence, to answer the question, “What did C.S. Lewis really think about homosexuality?”

The Vanauken Letter

Probably the single most-cited passage from Lewis’s writings for this purpose is a letter he wrote to Sheldon Vanauken, included in A Severe Mercy. We don’t have Van’s initial letter, but Lewis summarizes that Van and Davy have befriended a couple of self-identified gay students seeking advice from Van, who in turn is seeking advice from Lewis. Mark Shea reproduces the letter in full here at National Catholic Register.

The first thing to note is that Lewis rejects the consummation of same-sex desire out of hand, but he also rejects more than that. It seems that Van had been wondering whether perhaps a union between two men or two women could be sanctified as long as it was unconsummated. Lewis firmly dismisses this as “the wrong way.” This is notable for certain voices in the camp trying to leverage this text who have openly entertained the idea of vowed “gay, chaste unions” of the kind here endorsed at the Spiritual Friendship blog by Aaron Taylor. Even with the provision that one partner was gay and the other straight in a “vowed friendship,” Lewis clearly would have seen this as a deeply unhealthy way of trying to satisfy a privation. I highly doubt too that he would have agreed with Wesley Hill here that a couple who already considered themselves “married” could legitimately carry on as usual minus only the sex part, particularly if this involved “raising children” (!)

Lewis also addresses the problem of even private emasculating fantasies like cross-dressing, saying such “little concessions” are likewise no good. While he was known to express annoyance with stereotypical notions of what constitutes “a man’s man” or “a woman’s woman,” famously writing to a nun that he thought “there ought spiritually to be a man in every woman and a woman in every man,” clearly he had in mind at all times the ordinary bounds of masculine and feminine presentation. To the extent that he thought men should have in themselves something “spiritually” of the feminine, he seems to mean, as he writes here to Van, that men should “imitate the virtues” that are more typically attributed to women (gentleness, patience, etc.)

But the “money bit” in these circles is this passage:

The homo. has to accept sexual abstinence just as the poor man has to forego otherwise lawful pleasures because he wd. be unjust to his wife and children if he took them. That is merely a negative condition. What shd. the positive life of the homo. be? I wish I had a letter wh. a pious male homo., now dead, once wrote to me—but of course it was the sort of letter one takes care to destroy. He believed that his necessity could be turned to spiritual gain: that there were certain kinds of sympathy and understanding, a certain social role which mere men and mere women cd. not give.

Lewis’s “pious male homosexual” acquaintance seems to have anticipated a line in the Revoice playbook, namely that same-sex orientation may not be an absolute ill but could even be uniquely good, a thing to be channeled for unique social benefits. (See Wesley Hill here, or Eve Tushnet’s discussion here of how her lesbianism is a constructive part of whatever she does, even volunteering at a pregnancy center.)

Now, it may be that Lewis was more open to this suggestion than he should have been. Lewis never set himself up as a systematic theologian. He was constantly thinking out loud, especially in his letters, and would have been the first to tell any reader not to take his thoughts as gospel. To the extent that he was soft-endorsing this suggestion, in a moment of misplaced warmth and affection for his friend, it was regrettable, and we should see this as a place where he nodded. But it shouldn’t be mistaken for a fully worked-out theology of homosexuality.

Furthermore, the letter ends on this rather uncomfortable note:

I have mentioned humility because male homos. (I don’t know about women) are rather apt, the moment they find you don’t treat them with horror and contempt, to rush to the opposite pole and start implying that they are somehow superior to the normal type.

This nails homosexual psychology in general, and in particular it takes a pin to the balloon of Revoice’s self-styled “prophetic witness” to the church. Revoice founders like Nate Collins will claim that by virtue of their disordered sexuality (which, note, Lewis contrasts with “the normal type,” implying homosexuality is abnormal), they are able to stand apart from and above their “straight brothers and sisters” to issue a course correction on “idolatry of the nuclear family,” etc. Would they have found an “ally” in C. S. Lewis? Doubtful.

In conclusion, while this letter could reasonably be read as somewhat muddled, it is by no means a text that can be conveniently copy-pasted for revisionist political purposes in the wake of the sexual revolution.

The Arthur Greeves Friendship

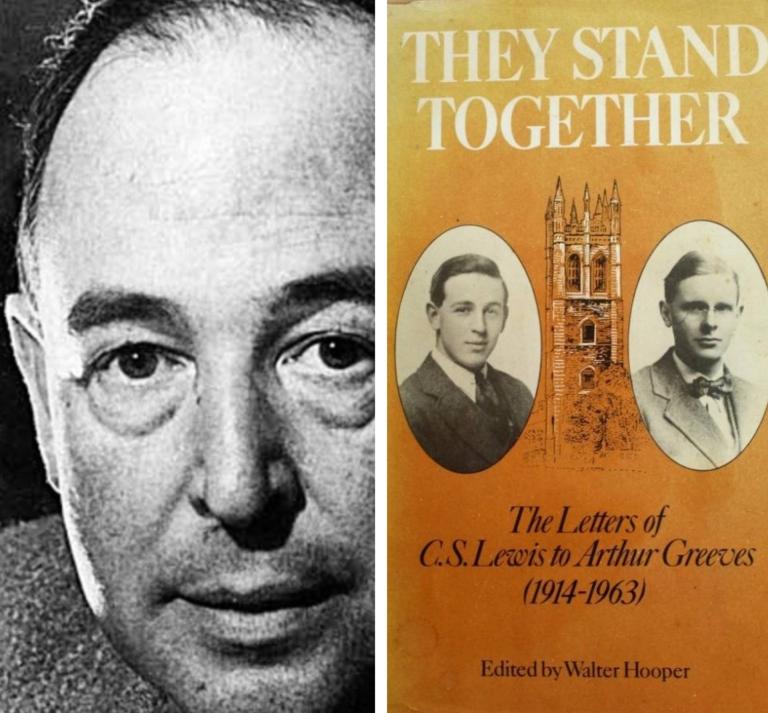

This is not so much a proof-text as an ingredient in the mix which deserves its own treatment. It’s been suggested that Lewis’s allegedly “liberal-minded” views on this topic might trace back to his close lifelong friendship with Arthur Greeves, who, we now know, was same-sex attracted. What is less often mentioned is that the world would never have known this had Walter Hooper not revealed and published certain portions of Lewis’s letters which Greeves had deliberately blacked out. It would seem that however severe Greeves’ affliction was, he had a measure of class and discretion about it, which class and discretion unfortunately weren’t reciprocated.

Greeves viewed himself as a Christian in the Quaker tradition, but he privately came out to Lewis while Lewis was still an atheist. Lewis, 19 years old at the time, wrote back, “Congratulations old man. I am delighted that you have had the moral courage to form your own opinions <independently,> in defiance of the old taboos. I am not sure that I agree with you: but, as you hint in your letter, <this penchant is a sort of mystery only to be fully understood by those who are made that way–and my views on it can be at best but emotion.>” (The bracketed bits were the bits Greeves scribbled out and Hooper revealed.)

Lewis’s response here is pretty much what one would expect at the time from a subversive young romantic heathen aesthete expressing solidarity with an old pal. There’s nothing of any significance to be gleaned from it when we come to evaluate his opinions on homosexuality as a mature Christian. But for some reason, Pastor Johnson lingers over this response in his appearance on Preston Sprinkle’s podcast, saying Lewis would have had no leg to stand on if he’d wanted to give Greeves a difficult time, since Lewis himself was openly flirting with sado-masochistic fantasies. (This information was also among Greeves’ blacked-out passages, information Hooper tells us in his preface he decided to reveal on the grounds that suppressing it would seem to give “the youthful lusts of the flesh” more “seriousness” than they deserved. I’ll let that bit of asininity stand without further comment.)

Lewis’s S&M phase tends to be trotted out for the uninitiated with something almost akin to relish. It shocks Sprinkle, who interrupts Johnson on the podcast to say “Wait, this is C. S. Lewis?” and asks for an instant replay. “Oh yes,” Johnson says casually, “there’s none righteous, no not one. We all have our issues. Don’t whitewash C. S. Lewis.”

Except Lewis only indulged these particular fantasies during this brief phase. They appear in a few letters, then fade away, never to return post-conversion. The old man had gone, the new had come. The end. But of course, that gets fewer clicks than “What you didn’t know about C. S. Lewis will SHOCK you.”

Returning to Greeves, it’s clear that he was sensitive and eccentric, painfully shy and intensely lonely, an archetypal “fragile golden boy.” It’s highly doubtful that he ever acted on his desires, given that it seems he could barely be enticed so much as to leave his house. According to a profile Lewis composed in 1935 for his family papers, Greeves suffered from the classic combination of a harsh father and an overbearing mother, which is a reliable co-factor for same-sex attraction. We can speculate that he might also have been on the autism spectrum. All of these things would very naturally have inspired Lewis’s sympathy, protectiveness and loyal affection, none of which he would have had reason to withdraw post-conversion. Indeed, his faith enabled him to pray for Greeves and vice versa, encouraging each other in virtue rather than perversion. “You needn’t ask me to pray for you, Arthur,” Lewis writes in 1944. “I have done so daily ever since I began to pray, and am sure you do for me.”

It must also be said that their relationship grew up organically in a context where there was no widespread cultural movement to normalize Greeves’ attractions, redefine the entire institution of marriage, or indoctrinate children accordingly. And to the extent that Lewis could have even slightly anticipated such seismic shifts, as we saw in the Vanauken letter he immediately rejected their implications. He might not have had Greeves in mind when he referred to the “male homo.’s” tendency to set himself up as superior if one doesn’t instantly react with “horror and contempt,” but perhaps Greeves also had some less than shining moments here. We’ll never know.

There is something not a little disingenuous in the contemporary attempt to make this intimate, private friendship a means to an end in a politically charged context. Lewis’s gift of generous Christian brotherhood, here extended to a particular friend, in a particular way, in a particular time, should be taken for no more and no less than what it was. It behooves us as Christians, as scholars, as decent men and honest readers, to leave it as we found it.

That Passage in Surprised by Joy

Some of you will already know what I mean by “That Passage,” but if you don’t, here it is. It’s an exceedingly dark summation of the sexual hazing system at Lewis’s old boarding school, where senior boys (“Bloods”) abused their power to exploit younger boys (“Tarts”) for sexual favors. These “Tarts,” by Lewis’s account, were willing participants in these rituals, even though Lewis uses the word “pederasty” to describe such “arrangements.” (It seems he’s here using it a little more loosely than average to refer just to the older/younger dynamic, whether or not the older had come of age yet.) In return for their services, they “had all the flattery, unofficial influence, favour, and privileges which the mistresses of the great have always enjoyed in adult society.” In physique, a Tart tended to be slighter and prettier than a Blood, and presumably played the receptive sexual role. In contemporary gay culture, he might have been described by a different t-word. By Lewis’s recollection, Tarts wouldn’t have self-described as exploited, not being “exactly” prostitutes. But then, neither would many actual prostitutes. The professional hustler, in his own mind, is always the author of his own story.

At the time, Lewis was more bored than shocked by this “system,” an attitude which the overseers apparently shared:

It is difficult for parents (and more difficult, perhaps, for schoolmasters) to realise the unimportance of most masters in the life of a school. Of the good and evil which is done to a schoolboy masters, in general, do little, and know less. Our own Housemaster must have been an upright man, for he fed us excellently. For the rest, he treated his House in a very gentlemanly, uninquisitive way. He sometimes walked round the dormitories of a night, but he always wore boots, trod heavily and coughed at the door. He was no spy and no kill-joy, honest man. Live and let live.

Lewis anticipates that his matter-of-fact retelling of all this might shock his readers, so he devotes a followup section to this reaction. “Here’s a fellow, you say, who used to come before us as a moral and religious writer, and now, if you please, he’s written a whole chapter describing his old school as a very furnace of impure loves without one word on the heinousness of the sin.” He famously says one reason for this is that homosexuality is one of only two sins he’s never personally been tempted by (the other being gambling). Another reason, which he proceeds to unpack, is that in its twisted way, he believes there was perhaps something good and affectionate to be salvaged out of it all. Perhaps the dominant Bloods, by at least fixing their attentions on someone or something outside of themselves, were thus even in this distorted sense distracted from pride:

If those of us who have known a school like Wyvern dared to speak the truth, we should have to say that pederasty, however great an evil in itself, was, in that time and place, the only foothold or cranny left for certain good things. It was the only counterpoise to the social struggle; the one oasis (though green only with weeds and moist only with foetid water) in the burning desert of competitive ambition. In his unnatural love-affairs, and perhaps only there, the Blood went a little out of himself, forgot for a few hours that he was One of the Most Important People There Are. It softens the picture. A perversion was the only chink left through which something spontaneous and uncalculating could creep in. Plato was right after all. Eros, turned upside down, blackened, distorted, and filthy, still bore the traces of his divinity.

This is myopic, to put it mildly. By Lewis’s own account, the system was its own breeding ground for “competitive ambition,” as jealousy ran riot and new Tarts replaced old. And a Blood who viewed “his” Tarts as conquests was hardly learning the art of self-negation thereby. I’m tempted to quote Lewis back at Lewis, recalling the passage in Screwtape Letters about the child who calls all things “mine,” including “my teddy bear,” by which he means “the bear I can pull to pieces if I like.” Unfortunately, as this passage stands, it’s been quoted by those who want to insist that there can be something good even in active gay relationships, and in fairness Lewis leaves himself open to that appropriation.

Lewis’s lead-in to this unpacking further lends itself to people who want to suppress a natural aversion to homosexual acts:

People commonly talk as if every other evil were more tolerable than this. But why? Because those of us who do not share the vice feel for it a certain nausea, as we do, say, for necrophily? I think that of very little relevance to moral judgement.

This is a rare stumble for Lewis, an unusually shallow thought for such a normally strong analytical mind. It wants a good dose of natural law as a corrective: Sexual acts which violate the natural telos of the body are intuitively unsettling by the natural light, which natural light is a form of revelation, just as a natural turning of the stomach at the sight of a dismembered fetus may be nurtured and nudged towards the pro-life view.

If the objection is made “on Christian grounds,” Lewis asks “what Christian, in a society so worldly and cruel as that of Wyvern, would pick out the carnal sins for special reprobation?” He maintains that “cruelty is more evil than lust.” But, again, by his own account, cruelty was baked into the Blood’s ways and means of making a Tart’s life miserable if he refused an advance. (And, too, anyone familiar with literature on promiscuity in “bona fide gay” contexts, which perhaps Lewis would have argued “the Coll” wasn’t, strictly, will understand how cruelty and lust can be inextricably intertwined.)

Lewis also suggests that there’s “very little evidence” that these activities led to “permanent perversion.” He’s confident that the Bloods “would have preferred girls to boys if they could have come by them,” and “when, at a later age, girls were obtainable, they probably took them.” In other words, they were the classic gay-acting boys who insist they’re “not gay.” This particular comment is distinctly British. In the UK far more than the US, there’s always been a strange notion of gay dalliances as a form of “sexual coming-of-age” for young men before they inevitably grow into straightness and assume their rightful position in society. (E. M. Forster’s bad novel Maurice is all about this, though Forster, himself gay, intends to suggest this “outgrowing” might be easier said than done. Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited is of course the quintessential literary case study here, as the protagonist even explicitly calls his eventual mistress’s brother her sexual “forerunner.”)

So how do we assess all this? No differently from how we’d assess any other passage of Lewis: honestly and fairly, pointing out where he’s been plucked out of context, but at some times, like this one, admitting where he’s myopic and foolish and inhibited by the particular blindnesses of his age. Perhaps, too, his evaluation is psychologically colored by the devastation of World War I, which “ate up” Bloods and Tarts alike. “They were happy while their good days lasted,” Lewis reflects. “Peace to them all.” Peace, indeed. But hindsight is not always 20/20. Even Lewis nods.

In Closing

This hasn’t quite been comprehensive, but I trust I’ve hit the high points. I could also have mentioned various places (including a bit in the above autobiographical passage which I didn’t quote) where Lewis expresses disapproval of sodomy laws. Granted, for his time this was edgy, but even for very conservative Christians in 2021 it’s nothing earth-shattering, and the sorts of libertarian arguments Lewis gives (it creates a blackmailer’s paradise, it’s an inappropriate intrusion of the state into the bedroom, etc.) are fairly garden-variety lines.

The picture one gets of Lewis in total as one steps back is of an imaginative theologian, a man constantly playing with ideas, usually with friends, and in the course of such play often hitting upon keen insights while sometimes also throwing out something foolish. He wasn’t afraid to provoke, and in that sense he could be regarded as ahead of his time, but he was still a man of his time, and as such, he will not be shoehorned into neat contemporary boxes.

I’ll quote one final passage, this from a letter to a school friend who converted to Catholicism, responding to something the friend had written about “two perverts” (we presume homosexual):

The stories you tell about two perverts belong to a terribly familiar pattern: the man of good will, saddled with an abnormal desire wh. he never chose, fighting hard and time after time defeated. But I question whether in such a life the successful operation of Grace is so tiny as we think. Is not this continued avoidance either of presumption or despair, this ever renewed struggle, itself a great triumph of Grace? Perhaps more so than (to human eyes) equable virtue of some who are psychologically sound.

Here we have in one place both Lewis’s bluntness and his compassion. His matter-of-fact acceptance that these desires are “perverted,” “abnormal,” and not “psychologically sound” and his instinctive desire to help navigate a path through dysfunction. Of course, navigating such a path is what voices in the Revoice sphere claim to be doing today. But unlike them, Lewis does not normalize, romanticize, or in any way heighten the dysfunction. He simply laments it for what it is, then recognizes that Grace can still work itself out even in our darkest and most shameful struggles. Perhaps, in the end, this is all that needs to be said.