Very few religions are more creedal in nature than Christianity and Islam. (In other words, their basis is a formal statement of beliefs, a creed.) Many of the ongoing conflicts today, as well as a great deal of violence historically, have occurred because of the creedalism that characterizes these two religions. The emphasis on holding formal beliefs even stirs enmity between followers of what are ostensibly the same overall religious frameworks. Sunni and Shi'a conflicts in Islam, for example, have existed since a generation after the death of Islam's founder; and today, there are still large numbers of Protestants who think of Roman Catholics as "not really Christian."

As I stated in the final page of my last column, however, deity-centered modern Paganism is not and should not be creedal. In fact, most polytheistic religions, both historically and as manifested in modern Paganism, are practical and experiential religions.

And yet, no religion is entirely without "belief" in some form. Some beliefs may not significantly shape daily life, like some forms of eschatology (end time belief) or reincarnation. Sometimes, however, the subjects of belief are much more essential to the religion. In my last column, I discussed the tendency, illustrated by John Halstead, to treat the very idea of gods as a matter of creedalism and belief. I think this is flawed, but only if "belief" is defined in the way most creedal religions do.

Unfortunately, since most people in Western society understand "belief" in a creedal context, it can be difficult to even begin a conversation about how belief operates in non-creedal religions. In my earliest, and rather unsophisticated, Pagan days (1992-1996), most of my friends, family, and acquaintances were Christian. Back then, if it was found out that I was Pagan, sometimes people would say, "Don't you find Christianity to be enough for you?" I'd explain to them that I couldn't get past the first line of the Nicene Creed, "We believe in one God." It wasn't because of the number of gods involved that I couldn't get past it—because I believe in one god, and another god, and another god, so I do ultimately believe in (at least) one god! Instead, I balked at the phrase "believe in."

No, my difficulty wasn't that I was an atheist (as many assumed, wrongly). It was because of the usual understanding of the phrase "believe in." The Middle English treatise on apophatic prayer, The Cloud of Unknowing, refers to belief as an "arrow of longing love" being fired into the "Cloud of Unknowing," which is understood to be the Christians' god. In this text, belief is a fallible means of making contact with something that may or may not exist. Yet, one "fires" the arrow into that uncertain atmospheric morass in the hope that there is something there with which to make contact. Mystics in Christianity fire this arrow with definite results. Many others, however, aim low, or don't even realize they're firing at a target, and get the disappointing results that one would expect.

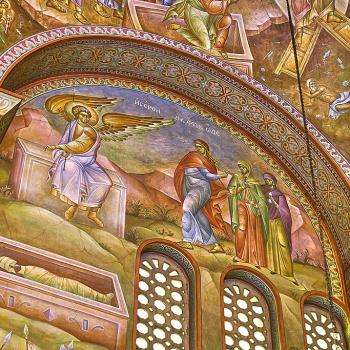

Fundamentally, this is the commonplace stance on belief: it is the act of deciding something exists without any proof. Many Christians talk about "belief in God" with no hope nor possibility of having experiential knowledge of that god, some even scoffing at the idea of "Christian mysticism" because it involves direct experience. This is truly a pity, given the beauty and power of the Christian mystical tradition . . . but I digress!

Modified for my own polytheistic position, my preferred creedal statement would be, "In the gods, I believe." Now, some might not see the difference between this and the Christian notion of "believing in God," but there's an important distinction to be made. The Latin preposition in translates as "in" in English, but depending on whether it takes the accusative case or the ablative case, it can be understood as either "into" or "within."

The way that "belief in God" is usually phrased in Latin is in the accusative case (Credo in unum Deum), and thus it is much more like the arrow-and-target situation I described above. In the phrase "In the gods, I believe," one can understand "in" as "within," which gives a far more appropriate nuance. That is to say: it is only within the gods (and within one's experience of the gods' reality) that one can believe at all—believe not only in the reality of the gods, but in anything and everything that exists.

In the words of Simone Weil from her work Waiting for God: "It does not rest with the soul to believe in the reality of God if God does not reveal this reality. In trying to do so, it either labels something else with the name of God—and that is idolatry—or else its belief in God remains abstract and verbal."