Tyrannius Rufinus tells this story of the destruction of the Serapeum of Alexandria late in the 4th c. A.D.:

One of the soldiers, better protected by faith than by his weapon, grabs a double-edged axe, steadies himself and, with all his might, hits the jaw of the old statue. Hitting the worm-eaten wood, blackened by the sacrificial smoke, many times again, he brings it down piece by piece, and each is carried to the fire that someone else has already started, where the dry wood vanishes in flames. The head goes down, then the feet are hacked, and finally the god's limbs are ripped from the torso with ropes. And so it happens that, a piece at a time, the senile buffoon is burned right in front of its adorer, Alexandria. The torso, which had remained unscathed, was burned in the amphitheatre, in a final act of contumely. [...]

A brick at a time, the building is taken apart by the righteous (sic) in the name of our Lord God: the columns are broken, the walls knocked down. The gold, the fabrics and precious marbles are removed from the impious stones imbued with the devil. [...]

The temple, its priests and the wicked sinners are now vanquished and relegated to the flames of hell, as the vain superstition (paganism) and the ancient demon Serapis are finally destroyed. (Historia ecclesiastica 2:23)

This is but one tale from the early Church Fathers of the destruction of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian sacred icons as Christianity rose to power in the Late Roman Empire. Starting in 389 A.D., Emperor Theodosius progressively decreed forbidden feast days and public sacrifices, and in 391 he commanded that "no one is to go to the sanctuaries, [or] walk through the temples." These are clearly methods for suppressing the traditional religions of the majority of the inhabitants of the Empire. Yet as we restore the worship of the Ancient Gods today, it is well we reflect on the spirituality necessary for the Christians to perform these acts of iconoclasm and contumely.

Most in our culture today are familiar with the ancient accusation of idolatry leveled by the Hebrew Prophets and others in the Bible against neighboring religions. The use of sacred icons as objects of worship was and remains commonplace outside of the Abrahamic traditions. For them, the use of imagery (especially anthropomorphic, but also zoomorphic forms) was forbidden by the Third Commandment of the Decalogue (Ex. 20:4-6; Dt. 5:8-10; etc.), and this commandment led to the general suppression of depictive art. Geometrical forms and calligraphy became high art forms in these cultures. (In some time periods this stricture was relaxed, but not generally for objects of worship.)

Catholic and Orthodox traditions engage in veneration (dulia) of iconography, which is seen as an acceptable but lesser form of spiritual engagement. The greater spiritual engagement of worship, technically termed latria or service, is reserved for their God. The Abrahamics are not the only aniconic traditions, however. The early Irish Celts and the early Buddhists both were, for example, and the impulse to not image the world or its inhabitants is ancient and widespread, if sporadic. Friction between iconic and aniconic peoples have at times led to significant violence, as the destruction of the Serapeum above typifies.

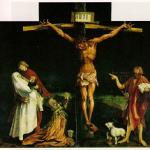

But the need to destroy the icons of a religion does not merely suppress the religion's material culture. There is a profound spiritual, or we might say magical, reason for the destruction. The Icons, or idols as their detractors would call them, were not simply works of stone, wood, porcelain, metal, or such. An Icon might be a work of high art or an unhewn stone, but in every case it was seen as an embodiment of the Deity worshiped through it. For this reason, the Icon was literally worshiped or offered latria or Divine service (as the Romans put it). This term is the basis for the word idol-latria.

For its detractors, this practice was the height of folly or the depth of sin. Their polemic centers on the worship of a stone or block of wood, an object made by human hands. Yet there is no evidence that the ancient peoples, or our contemporaries for that matter, confuse the Icon with the God, any more than we confuse a telephone with the person we are talking to. But you would not necessarily know this by listening to the speech of priests engaged in worship.

In worship, the Icon is typically addressed as though it is the person of the Deity. Whether giving words of praise, making food offerings, or dressing the Icon or shrine, the Icon is typically addressed as though there were a person present there. The reason for this behavior is that the Icon is the Deity, or more properly an incarnation of the Deity, what we might call today an instance. The 'actual' Deity is of course a structure of the world (at least for Pantheists)—that's what makes that Being a Deity. But the image, often anthropomorphic, is considered to hold the spirit of the Deity.