In sequel to my developing argument of the past two weeks on theological touchstones and angry partisanship, this week I offer a conclusion from my book Faithful Citizenship:

We are divided as nation and Church over partisan questions that are not worth coming to blows over—at least not in terms of Christian theology.

I don't in any way wish to diminish any of these issues, which are important, and often affect real human lives. I have sat with a pregnant student who felt she had no choice but abortion, and felt the grief of a woman who felt she could not have a child—but must. I have heard the anger of gay friends who wanted to be married in their own church and faith, and the passion of Christians who argued that homosexuality is simply wrong.

These issues are worth our deliberation, and affect real human beings, but I want to be clear about one theological issue. In terms of Christian understanding, almost all of them are secondary moral questions, however they may exercise us.

They are not what we would describe theologically as "essential" to salvation.

Brian McLaren talks about how people outside the Church are often most turned off by—or people inside the Church most often become people outside the Church because of—issues that a particular congregation or denomination has made into an essential part of Christian faith when really it is nothing of the kind. While particular churches and denominations may define themselves by certain political stands, nothing in the historic Creeds requires us, for example, to oppose abortion or promote traditional marriage; nothing requires us to decry capital punishment or support Christian pacifism.

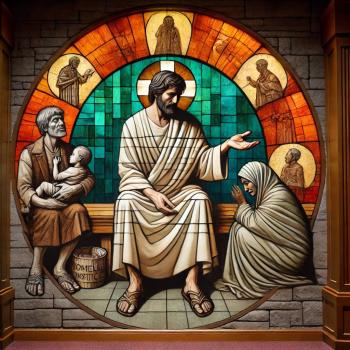

The Bible and Christian tradition may and do have things to say about these issues, and all of them, without doubt, deserve our thoughtful enquiry and active engagement so that we can choose how we live our lives in conformity with Christian teachings. But they do not, themselves, constitute beliefs essential to salvation, such as the belief in one God, belief in Jesus as the Son of God, or belief that the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus constitute, in some way, our redemption (and even these essentials have been argued—hence the existence of the historic Creeds!).

There is an old saying about how we deal with controversy within the Church (sometimes attributed to John Wesley, it is the motto of the Moravian Church): "In essentials, unity; in nonessentials, liberty. In all things, love."

We don't—and can't—agree on everything. And yet, we must live and work together.

Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels—who disappointed many Republicans (and some Democrats) when he chose not to run for president in 2012, articulated this hope that we could set aside the culture wars and focus on more substantive matters. He told a British interviewer that "the next president, whoever he is, 'would have to call a truce on the so-called social issues. We're going to just have to agree to get along for a little while.'" Similarly, Barack Obama first rose to public notice for speeches saying that America is not Republican or Democrat, Catholic or Protestant, Red State or Blue, but that all of us will have to work together to accomplish what must be done, a statement he reiterated in his 2012 State of the Union speech.

In essentials, unity; in nonessentials, liberty. In all things, love.

Still, we will have to address the fact that some of us have decided that our own important issues are essentials of the faith. We've mentioned Glenn Beck's argument that an attention to social justice marks a church or parish as un-Christian; pastors Gregory Boyd and Mike Slaughter have each written about how they lost members from their large churches for suggesting from the pulpit that God's take on a partisan political issue may or may not be the same as their parishioners. The Rev. Slaughter says that some of his congregants actually came to him and said "You are not preaching the Gospel!" whereupon he told them that he has been preaching the same gospel—the Trinitarian God, the lordship of Christ, the gospel as good news to all, especially the poor and disenfranchised—since 1979.