By Alexander Zaitchik

If witch-burning Puritans are the original jocks of American history, then the mystics surrounding Johannes Kelpius are the first goths. While the rest of the British colonies were still dutifully worshipping their angry Christian god, Kelpius and his followers -- who fled Austria to settle in Philadelphia during the late 17th-century -- busied themselves with astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah, and other "dark arts" with tangled roots in the Italian Renaissance, the Rosicrucian Enlightenment, and various (often fabricated) antiquities.

If witch-burning Puritans are the original jocks of American history, then the mystics surrounding Johannes Kelpius are the first goths. While the rest of the British colonies were still dutifully worshipping their angry Christian god, Kelpius and his followers -- who fled Austria to settle in Philadelphia during the late 17th-century -- busied themselves with astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah, and other "dark arts" with tangled roots in the Italian Renaissance, the Rosicrucian Enlightenment, and various (often fabricated) antiquities.

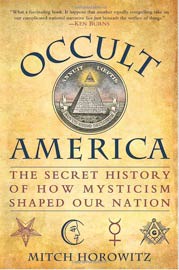

We meet Kelpius early in Mitch Horowitz's Occult America: The Secret History of How Mysticism Shaped Our Nation, an uneven but always interesting account of 400 years of New World Strange. Among the several misconceptions Horowitz seeks to dispel, the most foundational is the idea that Colonial America provided shelter only for persecuted Christian sects. Almost from the beginning, North America was also home to a fair number of those who, like Kelpius, had more arcane spiritual interests.

Horowitz never claims that these beliefs were as formative an influence as Christianity in the making of America, but after finishing his book, one can't help but wonder if maybe Ouija boards don't belong next to King James in every motel room. Horowitz ably chronicles how occult traditions have, over the centuries, deeply and consistently influenced the American mainstream -- sometimes entering the mainstream themselves in the process.

Many of the figures that populate Horowitz's narrative will be unknown to the uninitiated, but their impact is illustrated by the frequent appearance of more familiar names. Mormonism's founder Joseph Smith, after a childhood in the Hudson Valley's famously heterodox "Burnt-over District," was at the time of his death studying Hebrew and Kabbalah. Henry Ford was a fan of the New Thought leader Ralph Waldo Trine, and he often gave visitors copies of Trine's In Tune With the Infinite. Frederick Douglass left open the possibility that a magic "hoodoo" root (not to be confused with "voodoo") helped him secure victory against a cruel slave master.

One of the more surprising vignettes involves Henry Wallace, the New Deal figure best remembered today for his doomed third-party challenge to Harry Truman in 1948. As Horowitz shows, it wasn't Wallace's alleged ties to Communists that brought a premature end to his political career; it was his relationship with a shadowy Theosophist "guru" named Nicholas Roerich.

As often as not in Horowitz's history, mysticism meant money. Occult America offers numerous examples of hucksters popularizing esoteric ideas to make a buck. Almost all did so by preaching variations on the profoundly American idea of "the power of positive thinking" (or, in the first formulation, "the power of affirmative thought"). It first came to prominence in Jacksonian America, when a Maine clockmaker named Phineas P. Quimby came to believe he had cured his tuberculosis simply by refusing to believe in it. Quimby's insight, combined with the ideas of Mesmerists and Swedenborgians, gave birth to the movement known as New Thought.

Almost a century later, an Idaho druggist named Frank Robinson would build on New Thought premises to found and grow the world's eighth largest religion, Psychiana, largely by selling memberships (with a money-back guarantee) through mail-order magazine ads. Robinson's paying adherents received lesson plans that mixed mind-healing, prayer, and good old-fashioned Emersonian self-reliance. Ernest Holmes would employ a similar model to build the still-extant Church of Religious Science. By the mid-20th-century, New Thought had been further mainstreamed and repackaged for mass consumption in the form of best-selling books by Dale Carnegie, Napoleon Hill, and -- most famously -- Norman Vincent Peale.

Among the forgotten stories Horowitz tells is the role the occult played in the progressive social movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. The most famous 19th-century Theosophists, Spiritualists, and trance mediums preached a radically democratic view of religion, society, and individual empowerment that crossed barriers of gender, religion, and race. Many were active in the fight for women's rights, the abolition of slavery, and desegregation. "Spiritualism has inaugurated the era of woman," declared the Spiritualist suffragette Mary Fenn Love in 1853. Twenty years later, a trance medium named Victoria Woodhull became the nation's first female presidential candidate, nominated by a coalition of suffragists, abolitionists, and religious free thinkers who counted a wide array of occultists in their number.