Over last several months the pages on Washington Post's "On Faith" Forum, Newsweek, and now New York Times and Huffington Posthave been abuzz with the "Great Yoga Debate." One question being debated is "Is yoga Hindu or secular?" Several people have rejected the claim that yoga should acknowledge its "Hindu" origin and that such claim is yet another campaign by Hindu nationalists that need not be taken seriously.

Over last several months the pages on Washington Post's "On Faith" Forum, Newsweek, and now New York Times and Huffington Posthave been abuzz with the "Great Yoga Debate." One question being debated is "Is yoga Hindu or secular?" Several people have rejected the claim that yoga should acknowledge its "Hindu" origin and that such claim is yet another campaign by Hindu nationalists that need not be taken seriously.

Several points seem to be lost in this vociferous debate. First, the very word "Hindu" is difficult to define as religious or secular. While its common usage refers to people practicing Hinduism, etymologically it simply refers to people living across or near the river Sindhu, also called as Indus in English. The word is still often used by non-Hindus and non-Indians to refer to all people living in South Asia or even the languages used by people of South Asian origin. For instance, I am sometimes asked this question, "Do you speak Hindu?" Here the questioner is really referring to the language Hindi, which again is a reference to the people living in South Asia and speaking Hindi-Urdu, the twin language of India and Pakistan with shared grammar and vocabulary.

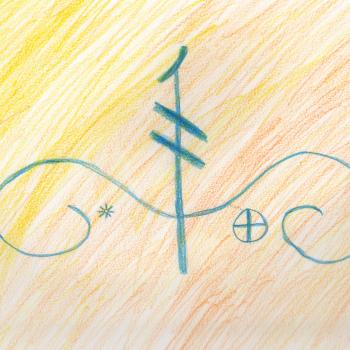

My point is that the very question of whether "yoga" is secular or religious has its origins in the history of the Western enlightenment, which separated the secular from religion. From the South Asian perspective, the very word Hindu is both religious and secular. Furthermore, for several millennia yoga has strived to transcend all kinds of dichotomies, for instance, between the body, mind, and soul. The very word yoga means to yoke or to join, not to separate or dichotomize! Absence of dichotomy is, of course, not limited to the term Hindu or yoga but many indigenous traditions in Asia, Australia, Africa, and in the Americas make no such distinction between 'religious' and 'secular.' So perhaps, it is time to remind ourselves that the concept or idea of 'religion' is not of the same kind in other cultures as it is in the West. In fact, several scholars have argued that there is no such distinct or tangible phenomenon in Asian cultures that can be called 'religion'. Virtually, every part of life is filled with religious (and secular) ideas including food, music, entertainment, health, education, and many other spheres usually considered 'secular' in the West.

Perhaps more importantly, why do some people insist that the Hindu "debt" to yoga must be duly acknowledged? In this age of globalization, ideas and trends will continue to travel in all directions. Even more than a century ago, Swami Vivekananda, one of the most famous Hindu yogis of all times, had this to say about the Indian spiritual ideas: "Whenever such a state [globalization] has been brought about, the result has been the flooding of the world with Indian spiritual ideas".

So, Hindus and people of Indian origin should indeed be happy that the prediction of their first Hindu monk in the West has indeed come true. Yoga has indeed flooded the American gyms and health centers with millions of practitioners all over the country. Why then some Hindus are mounting a campaign "to take yoga back"? They seem to be quite satisfied and even proud that several Westerners are leading yoga teachers and publishers of other Hindu books and magazines. For instance, one of the world's most prominent Hindu magazine Hinduism Today is published by Western Shaivites based in Hawaii with a huge number of subscribers from Indians in India and the Indian diaspora around the world. Whenever Western scholars, political leaders, or even industrialists go to India, they experience the legendary hospitality offered by Indians. Evidently, there is no tension on the racial or cultural or religious perspective, not at least from Indian side. What then is the driving force behind the recent not-so-friendly reactions from Indian diaspora?

One way to interpret this anxiety about yoga could be to look beyond yoga and study the issues related to biopiracy. Indian scientists, politicians, and activists seem deeply worried that the ancient traditions such as yoga and even indigenous spices and other food items such as Indian species of rice, turmeric, and other plants such as Neem and Tulsi would eventually be patented by the Western powers. This Indian concern is similar to the concern of Native Americans about their native symbols and legends being appropriated and exploited by business interests in the U.S. Perhaps the psychological and cultural wounds (both real and perceived) of indigenous people in India or elsewhere are yet to be studied and healed by Western forces. And that may be one way to bridge this gap of fear and insecurity among different cultures.