Karen: So what's this big news, then?

Daisy: [excited] We've been given our parts in the nativity play. And I'm the lobster.

Karen: The lobster?

Daisy: Yeah!

Karen: In the nativity play?

Daisy: [beaming] Yeah, *first* lobster.

Karen: There was more than one lobster present at the birth of Jesus?

Daisy: Duh.

~ From the movie Love Actually by Richard Curtis

I grew up in cities across the South, and in a small town in Oklahoma -- and all, at that time, were the kinds of places where it would not have occurred to anyone in my vicinity to ask questions about whether displays commemorating religious holidays belong on public land or Christmas pageants belong in public schools. In my small town, we marked the passage of time with public events, and Christmas displays in front of the police and fire station (we had no courthouse) were treated no differently than the civic fireworks on the 4th of July. They were a sign of community and a sign of civic spirit, and I want to remind folks about this -- or to inform them, if it has never occurred to them, that people might have valid reasons to permit sacred life to intrude into the secular and public spheres.

I won't claim that all the places I lived were monolithic -- Atlanta and Charlotte were large, culturally and racially diverse, and I know there were people who weren't Christian, although I would never have been allowed anyplace where I could meet them -- but my small town in Oklahoma was (at that time) monolithic: one black family, one Hispanic family, no out gays or lesbians, and if you weren't Christian, you certainly didn't advertise it.

Communities like this still exist, and I realize you can either romanticize or villainize them, depending on your tendencies. But both impulses are too simple. Me? I want to understand the impulses, and to understand what's at the heart of a desire either to permit (or insert) Christianity in the public square or to ban it from view and make it strictly a private matter.

Because there is no biblical prescription to celebrate Christmas -- and because for much of the Common Era, Christmas was either a pagan feast or a sensual free-for-all -- the tradition doesn't offer much theological wisdom about Christmas. Likewise, the Founding Fathers would not have known Christmas as a sacred occasion as we do today. Still, as with everything else in my life these days, I want to explore why I do what I do and believe what I believe, even if our sacred texts don't provide direct guidance.

I want to know, for example, why my liberal political brain thinks we must protect the rights of all non-Christians by banning public expressions of Christmas, particularly in territories where government intersects them.

I want to know why my conservative remembering brain thinks people should be allowed to enjoy such public expressions.

Since I carry in myself multitudes, and those multitudes often disagree like people outside my body, mostly in this essay I want to explore theologically what we gain -- and lose -- when we do either.

Early in the history of this column I proposed a Christian political ethic built around faith, compassion, and self-sacrifice -- the "I Am Third" ethic, I called it then. Lacking biblical warrant for Christmas (as we do), how might this ethic suggest we approach public displays of Christmas?

Well, if God Is First in this ethic, we might ask, how is God served best in this question? We might certainly argue that celebrating the Incarnation, the beginning phase of God's Kingdom coming on earth as it is in heaven, is pretty exciting stuff. So is the idea, at the heart of Christian celebration of Christmas, that we seek to love and serve others as we commemorate our own acceptance of God's gifts to us.

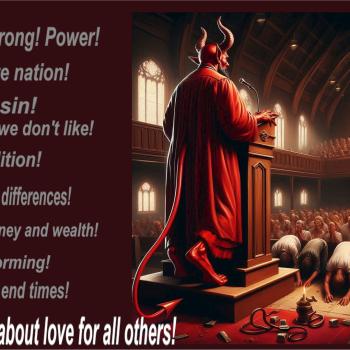

Do these displays need to be supported or even mandated by the State in order to honor God? On reflection, I think not. Legislating them takes the willing choice out of them, and it implies that God and God's message of love and reconciliation somehow need the protection of the State to prosper. History (and the present) makes me suspicious of any marriage between State and Church. When these two marry, unfortunately, it never seems to be the State that becomes more like the Church, but the other way around.

If My Neighbor Is Second in this ethic, then I likewise see two strains of thought here. If I'm a Christian, my first duty to my neighbor is that I permit her or him to see the love of God manifested through me. But how do I do that? For some Christians, particularly if we are conservative or evangelical Christians, that is by inserting Jesus (and God's ethic of life, as they understand it) in our neighbors' lives in any way we can manage it, like Jesus-shaped targets at a shooting gallery, popping up, parading across the line of sight, standing there big as life. Laws may help do that. And Christmas displays certainly don't hurt.