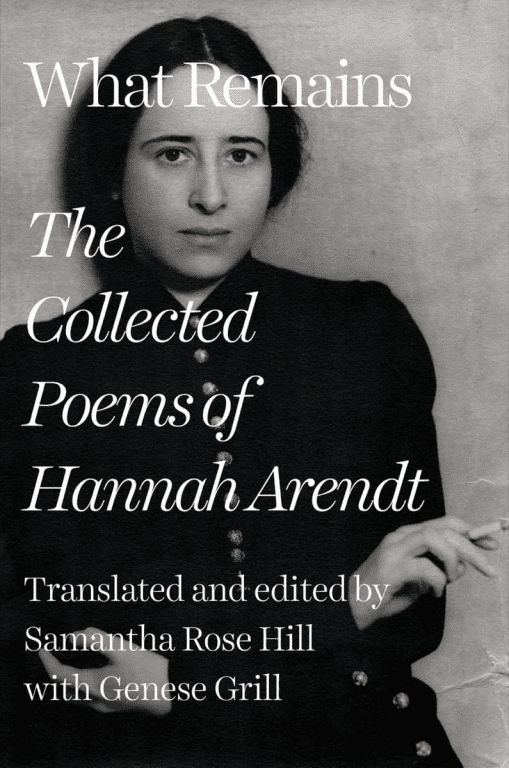

Hannah Arendt is best known as a political theorist who explained Nazi totalitarianism and evil. But did you know she also wrote poetry? Her poems reveal secrets for resistance.

I discovered the newly published volume of Hannah Arendt’s poetry on accident. Walking through my local library past the display of new books, What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2025), caught my eye.

Two months after the second election of Trump, I was deep in a malaise of anguish, anger, and alienation. And there was Hannah Arendt on the book’s cover pointedly looking at me from across the decades.

My eyes widened with wonder. The author of The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), The Human Condition (1958), and many other works of history and philosophy also wrote poetry? One of the most brilliant and significant thinkers of the twentieth century secretly penned poems?

I grasped the book like a drowning person grabs a life ring.

Hannah Arendt’s poems have kept me afloat these past two weeks as the swift currents of techno-oligarchal christofascism have swept us ever closer to the precipice. Now we have plunged over the edge; the illusions of the rule of law and democracy are behind us. As we gasp and sputter in the churning waters of chaotic evil, I throw out this lifeline of Arendt’s poetry to those who may also feel like they’re drowning.

You might ask, how can poetry help? Why poetry to resist fascism? What can a few lines of verse possibly offer in this hellscape opening before us?

The answer is that “poetic thinking” resists tyranny.

In the book’s introduction, we learn that Arendt asked a pivotal question in one of her personal notebooks: “Is there a way of thinking that is not tyrannical?” The collection’s editor, Samantha Rose Hill, (who co-translated the poems with Genese Grill) muses that what Arendt called “poetic thinking” is the answer to this question (xxi). Hill asserts that “it is the poets alone who bear the burden of truth in our world. They are our record-keepers, tending the storehouse of language and memory” (p. xxiii).

Arendt herself describes poetry as “shelter[ing] its core from evil intentions” (p. 115).

Why is poetic thinking important?

When you live in a society and culture that seeks to control your thoughts, silence your critique, command your mind’s obedience, and police your spoken and written words, poetry is an act of resistance. Poetry defies totalitarianism because it subverts hierarchy, inverts power, juxtaposes new ideas, and escapes the notice of banal stupidity.

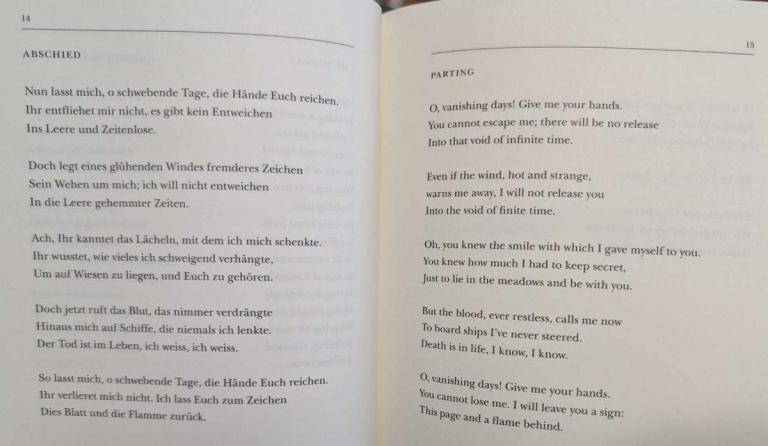

Even when state violence invades your sleep and wakens you to a worse nightmare than your dreams could conjure, poetry cuts a secret slit in the world they have forced upon you. You can escape into a niche, a room, a landscape they cannot touch. As Arendt wrote in a poem called “Parting” (p. 15):

O, vanishing days! Give me your hands.

You cannot lose me, I will leave you a sign:

This page and flame behind.

Poems in her “mother tongue”

Arendt (1906-1975) was a Jewish German philosopher who just barely escaped the Nazi regime in the 1940s. Though she found refuge in the United States and had a career in writing and teaching there until her death, she retained her love for the German language and German poets.

In fact, the editors included both the German and English-translated versions side-by-side to honor her “mother tongue.” Though I do not read German, I still skimmed through the original versions, especially noting the rhyme schemes of some poems that do not carry over into English. The editors also include helpful notes about idioms, phrases, and cultural references that we would otherwise miss.

Poetry survives and enables survival

There are seventy-one poems in this volume that span thirty-eight years of Arendt’s life, from 1923 – 1968. However, there are no poems recorded from the period of 1926-1941, due to her living under and then fleeing the Nazi regime during that time. Even still, she made a point of carrying her collected poems with her as she fled, as she survived internment camps, and as she made her way to the States.

But few knew of these writings. Only when novelist Mary McCarthy opened Arendt’s archives in 1988 did these private reflections come to light. And only now, thanks to Hill’s in-depth, dedicated, and faithful study and translation of the poems, can English readers begin to savor these morsels of creative and poignant reflection about her life before and after World War II.

For example, her very first poem wrestled with the existence of God with stunning crystalline brevity (p. 3):

No word breaks the dark –

No god lifts a hand –

Wherever I look

This tremendous land.

Now shadow hovers,

No form has weight.

And still I hear:

Too late, too late.

I have to admit that as the new regime took power in the U.S. on Jan. 20th, Arendt’s words gave voice to my feelings of dread and godlessness. The too-late-ness looms before us now, as heavy as storm clouds roaring across the sky.

Arendt and Heidegger – it’s complicated.

Of course, no examination of Arendt’s work is without controversy given her relationship with the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. The two met when she was his student in 1924. They developed a romance, though he was married and had children, and she was only eighteen at the time. Like her poems, Arendt kept their affair a secret. But even during her first marriage and beyond, she maintained contact with him.

What complicates this aspect of her life is that Heidegger was a spokesperson for National Socialism and the Nazi party. Such is the power of love that Heidegger could both declare his affection to her while also supporting a movement that would have sent her to the gas chambers. And such was her devotion to him that in the 1950s, she defended him against critics and said that he had merely gotten swept up in the movement without truly understanding it.

We might wonder: how can one bracket love from the politics of genocide? Yet there can be no denying the bond of yearning and love between them as seen in these verses from her poem “Summer Song” (p. 27):

Fields—where no one can hear us.

Woods—where no one can see us.

All is held in strict silence.

We suffer when we love.

Poetry as mirror and muse

Hill stresses that one need not write poetry to be a poetic thinker. Anyone who pursues independent, creative, critical ideas can think poetically. But since I actually do consider myself a poet, I found that Arendt’s words not only mirrored some my own thoughts in this liminal moment, they also reignited my impulse to write poetry and rediscover my capacity for resistance.

Since my pre-teen years, I delighted in the ways I could play with words, crafting them into clever pieces that captured my spirit. Thanks to teachers in middle school and high school, as well as my parents who encouraged my writing, I kept at it, even when my words were awkward and cringey. As a minister, preacher, seminary professor, and activist, poetry has often been a source of solace and inspiration for me.

Now, Arendt has shown me that I need to return to poetry to shore up my sanity for what lies ahead.

“I’m in life without a helm.”

The day after the certification of the election, when feelings of anger and betrayal consumed me, I found my bereft spirit reflected in these words from one of Arendt’s untitled poems (p. 17):

Go through days without right.

Speak words without weight.

Live in darkness without sight.

I’m in life without a helm.

Above me only this vastness

Like a new dark black bird:

The face of night.

But unlike Arendt, I know that my poetry will be public.

For better or worse, I will offer my poems as Arendt has unknowingly blessed me with hers. In fact, I wrote a poem about the risk of this decision:

Where is the secret space

they cannot find,

cannot touch?

Why, when I find it,

do I fling it open,

recklessly, boldly,

defiantly?

Why can I not keep silent,

protect the words from being

taken and used like a bludgeon

or a knife that finds the soft spaces?

Like Scripture, poetry takes on new meaning as we follow the spiral of our lives.

I return to poetry in the Psalms every year and am surprised to hear my own voice in places where my younger self had no capacity for recognition. Psalm 41:9, for example, speaks of the betrayal I now feel from those who once I trusted to protect us:

Even my bosom friend in whom I trusted,

who ate of my bread, has lifted the heel against me.

Psalm 55, too, voices the anguish of recognizing the cowardice and duplicity of those who we once counted as allies:

20 My companion laid hands on a friend

and violated a covenant with me

21 with speech smoother than butter,

but with a heart set on war;

with words that were softer than oil,

but in fact were drawn swords.

Arendt’s poetry will be my companion in the spiral.

Hannah Arendt lived through the last golden days of her society and culture. She watched the pillars of trust crumble, the foundations of society teeter and tip into a crater of cruelty. She scrambled and survived, using poetry to find handholds of sanity and self-reflection.

Yet her poetry also articulated beauty in nature, in human tenderness, in the longing for home. Everywhere she went, she carried her poems like seeds tucked away. She wrote:

Shell, when the seed breaks through,

show the world your dense interior.

Thanks to Samantha Rose Hill and Genese Grill, that dense, complex, heartbreaking, heartlifting interior of Hannah Arendt’s poetry has broken through.

I invite you to find your own seeds, cultivate your own poetic thinking, and tend to the poems of your resistance.

Read also:

315 Today: A Poem about Gun Violence

The Origami of Grief: Unfolding, Refolding, Enfolding

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching and Social Issues: Tools and Tactics for Empowering Your Prophetic Voice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024), Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her book, Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, was co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).