Bishop Budde’s sermon for the Inauguration Prayer Service models effective prophetic preaching. Let’s break it down.

The sermon heard ‘round the world

On Tues., Jan. 21st, I began receiving messages from friends about a sermon The Right Reverend Mariann Edgar Budde, the Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, preached at the Washington National Cathedral with Donald Trump in attendance.

I teach preaching and worship at a seminary. I’ve probably preached close to a thousand sermons in my career as a minister. I’ve conducted research with thousands of preachers on ministry, preaching, and social issues. [Preachers can take my latest preaching survey here.] And I’ve written books about how to preach effectively, especially in politically-divided congregations.

In the days following the national prayer service, the public conversation around this sermon has surpassed any I’ve seen in my decades of ministry and teaching.

But I must admit, I did not immediately watch Bishop Budde’s sermon.

Why I initially hesitated to watch Bishop Budde’s sermon

The week prior, some of my Episcopal colleagues shared how angry they were that the National Cathedral was hosting this prayer service for the nation as part of the inauguration events, a tradition dating back to 1933.

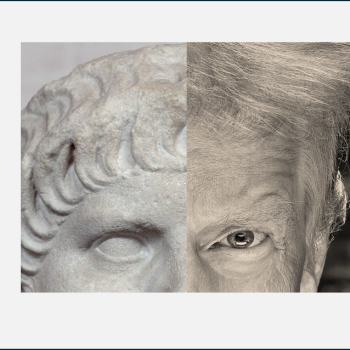

At first, I shared their dismay. Inviting Trump and his entourage into that hallowed space for a blessing felt blasphemous. I refused to watch such a distinguished church normalize and legitimize the ascendency of a man hell-bent on corruption, violence, and self-serving cruelty.

But the next morning my 18-year-old son held up his phone for me to see. There was a picture of Bishop Budde standing at the pulpit surrounded by a spray of white and red flowers.

“Mom! Did you watch this sermon?”

Surprised, I asked if he had watched it.

“Of course!” he replied.

What made you want to watch a sermon? I asked.

“It’s all over the internet, Mom. You need to watch it.”

And what did you think about Bishop Budde’s sermon?

“I think Bishop Budde’s sermon one of the bravest things I’ve ever seen.”

For a young adult to say this about a sermon moved me. So I watched the video of Bishop Budde’s sermon.

As a preaching professor, I analyze the context, use of the Bible, form, structure, content, tone, and delivery of sermons. As I watched her sermon, I realized that we can learn important things about effective preaching from Bishop Budde’s address at the prayer service for the inauguration.

Also, from the backlash she has received, we can glimpse what many preachers are facing in their own pulpits.

Overall, Bishop Budde’s sermon illustrates 11 lessons about prophetic preaching.

1 – Know your audience and context

Bishop Budde’s sermon is categorized by we call “occasional preaching,” meaning that it is crafted for a particular occasion. Sermons for funerals, weddings, and a service like the one held at the National Cathedral are all examples of occasional preaching.

The worship service for this solemn occasion was not just ecumenical but also multifaith. [See the bulletin here]. Thirteen worship participants representing seven faith traditions had roles in reading sacred writings, offering prayers, and leading in music and singing. So, Bishop Budde knew she had to preach a sermon that would speak not just to her Christian listeners but resonate with people from other faiths.

She also knew that the person occupying the office of one of the most powerful nations on earth was listening. And, given the “harsh” moment we are in, as she described in an interview, she had to think very carefully about her words and her delivery.

2 – Tone matters

Before I watched the video, I assumed from seeing critics lambasting Bishop Budde’s sermon that she had preached with a strident “in-your-face” tone that many associate with a strong prophetic sermon. Trump himself posted that she is “a Radical Left hard line Trump hater” who “brought her church into the World of politics in a very ungracious way. She was nasty in tone.”

Then I watched the sermon for myself. What I saw and heard was a steady, compassionate, firm yet gentle voice speaking with both clarity and humility. She did not yell. She didn’t accusingly wag her finger or have a snarky vibe. Her delivery was warm, inviting, and respectful.

In other words, she modeled exactly what a good preacher should do when delivering a sermon.

So why would her sermon be characterized as “nasty in tone”?

3 – Know your personal risks and vulnerabilities

Delivering a prophetic sermon involves risks, especially for those who have heightened personal vulnerabilities. For my book Preaching and Social Issues, I developed an assessment tool for preachers to gauge what approach to take. [Preachers can take the 5-minute assessment here.]

The fact that the sermon for the prayer service at the National Cathedral was preached by a woman, would raise the ire of anyone cemented in the ideology of patriarchy. Had she fawned over the man, mewled empty platitudes, and ignored or distorted Scripture to serve his ego, she might have been spared his and his minions’ wrath.

But Bishop Budde took a vow to be true to God, follow Jesus, and trust the Holy Spirit. And she did so with dignity, poise, confidence, and kindness, which is what any good homiletics professor would teach their students to do.

And despite the right-wing attacks, the fact is that her sermon was biblically and theologically sound.

4 – Build your sermon on a solid biblical theme

Bishop Budde’s sermon began by reminding her listeners that unity is the intent of this prayer service. But she quickly distinguished unity from agreement, noting that the kind of unity she’s talking about “fosters community across diversity and division.” This unity is what fosters the common good and enables people to live in freedom together.

The biblical passage for the sermon was Matthew 7:24-29, Jesus’s teaching about following his words being akin to building one’s house on solid rock instead of shifting sand. When the storms come, only the house built on solid ground will remain standing.

Bishop Budde pointed to unity as the solid rock on which our nation should be built. In this way, she made a strong connection to Scripture and immediately demonstrated its relevance for our current time.

5 – Choose strong illustrations

Bishop Budde again clarified what unity is not. It’s not “conformity, victory, polite weariness, or passivity born of exhaustion.” Unity is also not partisan. Rather, it’s a way of being together that “encompasses and respects our differences.”

She then emphasized the relational quality of unity that requires us to “care for each other, even when we disagree.” She illustrated this point by lifting up the dedication of first responders and frontline workers who help their fellow citizens in natural disasters and emergencies without ever asking who a person voted for.

This kind of unity is sacrificial, she explained, requiring us to give of ourselves just as love does. And this love is not just for our neighbors but for our enemies, she said, referring to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:33-34).

6 – Use strong and accurate theological claims

Bishop Budde made simple but powerful – and biblically accurate – claims in her sermon. We are to be merciful as God is merciful (Luke 6:36) and forgive as God forgives (Eph. 4:32). Jesus, she reminded her listeners, went out of his way to welcome the outcasts of his day.

Yet, praying for unity means nothing if “we act in ways that further deepen the divisions among us,” she noted, deftly disarming the “thoughts and prayers” rhetoric so often used around issues such as gun violence. “God is not impressed by our prayers when actions are not informed by them,” she said in a powerful theological claim.

7 – Be realistic and gospel-centered

Bishope Budde’s sermon did not downplay the fact that power and wealth are skewing our discourse in America about what kind of people we should be and what we should value. She recognized the diversity of views competing in our society and that there are winners and losers in the political realm. But when those interests impact policy to the point that everyday people suffer the loss of their rights, their livelihoods, and their dignity, then unity is unattainable.

Given this reality, she emphasized the moral imperative of caring. This is a core gospel-centered teaching, but it flies in the face of those who value winning at all costs.

So why should the “winners” care about those who suffer, much less unity? Because “the culture of contempt has become normalized,” a trend that is counter to the teachings of all faiths, especially the gospel of Christianity. Bishop Budde named the reality of outside forces benefiting from exacerbating the polarization in our country. “It’s a worrisome and dangerous way to lead a country,” she warned.

8 – Be confident in your authority

Bishop Budde’s sermon was no Facebook rant or flaming Twitter/X thread. She claimed her authority as a person of faith surrounded by people of faith who trust in God to help them work toward the aspirations of the Declaration of Independence. In this way, she also claimed authority based on a founding and foundational document of this nation that declares the equality and dignity of all people.

This led her to return to the Matthew passage about building a house on solid rock and to identify three pillars for this foundation. In other words, she invoked the authority of Scripture repeatedly as the basis of authority for her message.

9 – Give clear, actionable ways to live out the message

The second half of Bishop Budde’s sermon identified and explained three pillars for the foundations of unity. Listeners could clearly follow her logic and remember her points, a requirement for any good sermon.

“Honor the dignity of every human being”

Noting that all the faiths represented in the chancel affirm the inherent dignity of every human being, Bishop Budde explained what this looks like in real terms. It means “refusing to mock or discount or demonize those with whom we differ, choosing instead to respectfully seek common ground.” When agreement is not possible, however, we must “hold onto our conviction without contempt for those who hold differing views.”

This alone would have been enough to trigger a Tweet-storm from Trump and his devotees. For fascists (and I use that term because Trump himself has demonstrated his devotion to fascism in multiple ways), no one deserves dignity in and of themselves. Value can only be recognized in those who are White, who ascribe to a certain ideology, and who are loyal to the power structure.

For Bishop Budde to claim inherent dignity for all by virtue of having been created by God is an affront to those who believe themselves to be gods.

“Honesty”

“If we’re not willing to be honest, there’s no use in praying for unity because our actions work against the prayers themselves,” Bishop Budde explained as she described the second pillar of unity.

Of course, given the age we’re in with rampant disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda, discerning the truth is sometimes challenging.

But, as Bishop Budde admonished, when we know the truth, we are obligated to speak that truth, even when it costs us. And we must speak that truth firmly as well as with humility, which is the third pillar for unity.

“Humility”

Humility is necessary because it keeps us from demonizing those who disagree with us, those we label “bad” while we believe ourselves to be “good.” Bishop Budde modelled this humility in her sermon by refusing to label anyone good or bad even when pointing out where we stray from the standards and foundations for unity.

Humility allows us to recognize each other’s humanity even when we differ with someone based on culture, demographics, politics, or personal decisions. And it was from this posture of humility that Bishop Budde made her final plea to the president.

10 – Stick the landing (conclude the sermon effectively)

At the end of Bishop Budde’s sermon, she addressed the president directly as a human being, asking for mercy on behalf of those who are scared in our country right now. [See the full transcript of the last part of the sermon here.]

In the name of “our loving God,” she asked him to be merciful to gay, lesbian and transgender children who fear for their lives. To the people without proper citizenship documentation “who pick our crops and clean our office buildings; who labor in poultry farms and meat packing plants; who wash the dishes after we eat in restaurants and work the night shifts in hospitals.” To people who are “fleeing war zones and persecution in their own lands to find compassion and welcome here.”

In other words, she stood in that sacred, public space — facing the fascist — and asked for mercy on behalf of those who have no access to such a space. She used her privilege as an ordained minister to speak for those whose lives are threatened. And she did so knowing that she would be putting her own life at risk.

11 – Count the cost

There’s one more thing my son said about Bishop Budde’s sermon.

“I don’t think it will make a difference. It won’t change anything. Trump will never change,” he said.

We talked about what it means to do the right thing even if there’s no hope of it making a difference.

What I tell my students, I said, is that preachers have an obligation to speak truth to power. It’s what we agree to in our ordination vows. The Bible calls us to preach the word of God, even if people refuse to listen, and even if we get backlash. It’s about having integrity and living into our vocation.

Speaking truth to power

In his preface to Preaching in Hitler’s Shadow, a collection of sermons resisting the Nazi regime in Germany, editor Dean G. Stroud states that “the church should have spoken out directly and boldly against Hitlerism,” but the few did. For those who chose to speak out, “such public statements enraged the Nazis rather than changed them” (ix-x).

As a result, many who made public statements against Hitler and the Third Reich suffered through loss of their positions, imprisonment, and even death.

“Still, there remains the demand of the gospel to speak out against injustice, not only in the hope of converting the oppressor but also under the Christian obligation to speak truth to power,” says Stroud (x).

Some preachers are doing the work

I can tell you that in my eight years of researching preaching about social issues with clergy and congregations, there are many courageous folks out there in pulpits doing exactly what Bishop Budde did in her sermon. They are faithful to the Bible, theologically sound, respectful in their tone, and courageous even when they know they’ll get pushback.

Like Bishop Budde, they’ve dealt with mischaracterizations of their intent, deliberate misunderstandings of their message, and even threats to their positions and wellbeing.

In a future post, I’ll explore just why these very basic, very biblical sermons that are in no way offensive to the gospel are received with such hostility by some listeners, including those who ascribe to Donald Trump’s ideology.

In the meantime, I encourage these preachers to hold fast to their faith, draw courage from the Holy Spirit, continue preaching the message of Jesus, and trusting the power of God to sustain them.

And if you’re one of these preachers, I urge you to connect with colleagues who share your convictions and can support your preaching vocation.

[Are you a preacher in the U.S.? You can help me with my research studying ministry, preaching, and social issues by filling out this survey.]

[Thinking of addressing social issues in a sermon? Preachers can take this 5-minute assessment of their strengths and vulnerabilities here.]

If you are a clergy person who is looking to connect with other Christian leaders in this work of resisting and disrupting Christian nationalism, check out the Clergy Emergency League, a group I co-founded in 2020.

Read also:

Mercy Plea by Bishop Budde Mirrors 3 Bold Biblical Women

Preaching After the 2024 Election: Sermon & Ministry Tips

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. She is a past president of the Academy of Homiletics. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA or AOH; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching and Social Issues: Tools and Tactics for Empowering Your Prophetic Voice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024), Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her book, Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, was co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).

BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/leahschade.bsky.social

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/