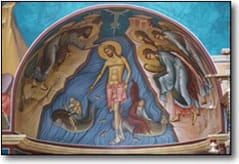

Left: Painting of the baptism of Jesus in the new Greek Orthodox church at Bethany, Jordan. Right: remains of the 6th century Byzantine shrine at the traditional site of the baptism of Jesus, at Bethany/Bethabara in Jordan. (Photos by William Hamblin)

Left: Painting of the baptism of Jesus in the new Greek Orthodox church at Bethany, Jordan. Right: remains of the 6th century Byzantine shrine at the traditional site of the baptism of Jesus, at Bethany/Bethabara in Jordan. (Photos by William Hamblin)

Most Christians naturally think of John the Immerser as a forerunner of Jesus, but it is clear that not all Jews of the first century saw things this way. Many saw John as a prophet in his own right. The Gospel of John thus wants to emphasize that the Baptist is the forerunner of the Messiah, but is not himself the Messiah (Jn. 1:20), probably to counteract claims of disciples of the Immerser in the first century. There are hints in the New Testament of followers of John who did not accept Jesus as the Messiah. These movements continued during the first centuries after Jesus. The most important ancient Baptizer community was the Mandaeans, who still survive today in southern Iraq and continue to practice ritual baptism in John's name.

John and Jesus were the two best known Jewish prophets from the first half of the first century, though there were actually many others, mainly known through brief notices by Josephus. Many of these first-century prophets and messiahs were executed or otherwise killed by members of the Jewish and Roman aristocracies. John the Immerser may have been a better known prophet in the mid-first century than Jesus, since Josephus, the major Jewish historian of the period, devotes about three times as much space to his discussion of John the Immerser as he does to Jesus (Antiquities, 18.5.2 [John] and 18.3.3 [Jesus]). This may reflect the relative impact of the two prophets in the minds of aristocratic Jews of the first century.

John the Messiah?

The Beloved's account of the Immerser begins with the "Jews of Jerusalem" sending "priests and Levites" to question John (1:19). They ask three questions. Is John: 1) the Messiah, 2) Elijah, or 3) "the Prophet" (1:20-21, 25)? He answers each question negatively. Obviously the Jerusalem authorities would not have asked these questions if rumors hadn't been circulating that John was each of these figures. So, who are these three eschatological figures, and why would first-century Jews suspect that John might be one of them?

- Messiah. The term Messiah is a transliteration of the Hebrew māšîaḥ, which means one who has been anointed with olive oil. Christ, on the other hand, is an anglicized transliteration of the Greek word christos, which likewise means "anointed." In the Septuagint, christos (and its variants) generally translate the Hebrew word māšîaḥ. In the Hebrew Bible, priests, kings, and sometimes prophets were anointed as part of a ritual of consecration. The "anointed/māšîaḥ"thus generally had reference to either a king or priest in ancient Israel. This is most striking in Isaiah 45:1, where YHWH calls the Persian king Cyrus his "anointed" or māšîaḥ/christos. As we shall see, for John, Christ uniquely and simultaneously fulfills all these three of these roles—prophet, priest, and king—and thus is the ultimate "Anointed One."

John the Beloved himself makes this linguistic connection between Messiah and Christ clear in John 1:41: "‘We have found the Messiah (messias)'—which is translated Anointed (christos)" (see also 4:25). Thus John is consciously using the Greek word christos to translate the Hebrew māšîaḥ. In English, Messiah is a transliteration of the Hebrew māšîaḥ/anointed one, while Christ is the English transliteration of the Greek christos/anointed one. Christos itself is the Greek translation of the Hebrew māšîaḥ. This creates three synonymous words in English—Messiah, Christ, and Anointed One—for precisely the same ancient concept. The name Jesus Christ in English is equivalent to "Jesus the Messiah" or "Jesus the Anointed One."

At the time of Jesus there was widespread eschatological expectation of the imminent coming of the Messiah. However, not all Jews believed the coming of the Messiah was near, and different Jews understood the nature of the expected Messiah quite differently. Most believed the Messiah was to be the prophesied ideal righteous king who would defeat Israel's enemies. Some believed he would be a mortal militant leader of armies. Others expected a more supernatural Messiah, accompanied by miraculous signs. Still others thought that the Messiah would be an exalted Son of God. As we shall see the concept of Son of God and Messiah are synonymous for John (1:49, 11:27, 20:31).

- Elijah. The expectation of an eschatological Elijah derives from two biblical passages. First, Elijah was taken into heaven in without dying (2 Kg. 2.1, 11), and second, Malachi prophesied that Elijah would return "before the great and terrible day of YHWH" (Mal. 4:5). Thus among many first-century Jews, the return of Elijah was an expected sign that the eschatological day of YHWH, including the coming of the Messiah, was at hand. Some intertestamental texts expressed the same idea (1 Enoch 90:31, 89:52; Sirach 48:10-12). Some contemporaries also thought Jesus was Elijah returned (Mk. 6:14-15, 8:27-28; Mt. 16:13-14; Lk. 9:7-8, 18-19). According to the Beloved, John the Immerser denied that he is Elijah (1:21-22), but Matthew reports that Jesus taught that John was Elijah returned (Mt. 11:13-14, 17:10-13; cf. Lk. 1:17). Elijah's appearance at the Transfiguration (Mk. 9:2-8; Mt. 17:1-8; Lk. 9:28-36) probably reflects this same eschatological expectation.

- Prophet. In first-century Israel there was a widespread (though not universal) belief that prophecy had ceased in ancient days, and a hope for the coming of a new prophet and new prophetic age (1 Maccabees 4:46, 14:41). More importantly, however, Moses had prophesied that there would arise a prophet like Moses (Dt. 18:15-19). Early Christians saw Jesus as this Moses-like prophet (Acts 3:22, 7:37), who brought the new covenant. The Qumran sectarians had similar views: "there shall come the prophet and the messiahs of Aaron and Israel" (1QS9.11 = Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 110). (Note the belief here in a priestly Messiah of Aaron's line, and a royal Messiah of David's line.)