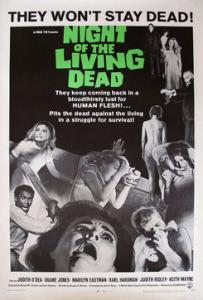

As a genre, horror cinema has always spoken to the broader fears and values of cultures and societies at particular moments in time. During the 1950s, the prevalence of monster films such as Godzilla and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms spoke to American fears over the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Similarly, films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Night of the Living Dead commented on American fears of communist infiltration and McCarthyism in the 1950s and white backlash to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. During the 1980s, the slasher subgenre experienced a renaissance, where films like Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), exposed American audiences to gratuitous scenes of violence and sex in a post-Vietnam world that was navigating the AIDS pandemic. What’s more, these films showed that even white suburban middle-class America could fall victim to the horrors of interpersonal violence. Post 1999, the horror genre experienced what many might consider to be a slump. Into the 2000s and 2010s, the market became oversaturated with any number of remakes, reboots, and the increasingly popular “requel,” or direct sequels to classic films that seek to reboot the franchise, simultaneously appealing to fans, new and old.

Religious horror, however, has been experiencing something of a renaissance beginning in the mid-2010s and extending to the present day. When thinking of religious horror, one might think of writer Frank E. Peretti, who has been dubbed by some as the Stephen King of Christian fiction. Nevertheless, the religious horror American audiences are consuming today is not marketed for Christians to consume as an alternative to secular culture. Films like Heretic (2024), The First Omen (2024), Immaculate (2024), The Exorcist: Believer (2023), The Nun II (2023), The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It (2021), and TV series like Midnight Mass (2021) are all examples of religious horror that have come out in the last five years. Moreover, these films are ecumenical in the sense that multiple faiths are represented, including Mormonism, Roman Catholicism, Pentecostalism, and Hoodoo. These are films that engage with religious themes, marketed to secular audiences. Nevertheless, they are still rife with violence, sex, profanity, and illicit practices that lead conservative Christian websites like gotquestions.org to call the faithful to set their eyes on things not of this world.

To be sure, religious horror films are not a new development within the genre as a whole. Early examples include Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), and Carrie (1976). That spurt of religious horror also certainly spoke to broader discontent in American society. A sense of impending dread permeated American life in the wake of the upheavals of the 1960s and the ongoing war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal, which was channeled into films about lurking evil and demonic possession. Even so, the boom in religious horror we are experiencing in this particular moment in American history can speak to broader issues where religion intersects with secular culture, especially with regard to gender and sexuality. Developments like Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, and right-wing panic over transgender athletes have increasingly highlighted the ways in which the worlds of religion and secular culture bump and grate against each other.

Haunting Social Commentaries

Scott Beck and Bryan Wood’s 2024 film Heretic illustrates a broader trend among American religion known as the deconstruction movement. Deconstruction, while not limited to any faith community in particular, has an especially large population among former evangelicals. The #deconstruction has over 158,000 posts on Tik Tok alone. Deconstruction is a process during which a person critically re-examines their faith, and in many cases, rejects the faith in which they were brought up. Popular authors among the deconstruction movement include Rachel Held Evans, Richard Rohr, Nadia Bols-Weber, and so forth. Issues that have caused a great many evangelicals to deconstruct their faith include sexual abuse within the church, women’s roles in ministry, and inclusion of LGBTQ+ identifying individuals at all levels of church life. The three central characters of Heretic are emblematic of this movement.

The film follows Mormon missionaries Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton as they attempt to convert a reclusive Englishman known only as Mr. Reed. Sister Paxton, confident in the veracity of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, represents a sort of pre-deconstruction phase. Having been born and raised in the Church, her approach to her work as a missionary is by the books, and she is steady in her convictions. By contrast, Sister Barnes was not raised in the LDS Church, and admits that she and her mother “shopped around” before settling on the Mormon Church. This represents a sort of early deconstruction phase, in which Sister Barnes inhabits a liminal space on the borders of Mormon orthodoxy, and the secular world. Sister Barnes, while not as steadfast in her faith as her missionary sister, is well versed in world religions, and is able to hold intellectually her own against the film’s antagonist, Mr. Reed. Reed, represents a totally deconstructed worldview to an extreme degree. Not only is he well-versed in the history of world religions, he is willing to enact physical violence against these girls in order to poke holes in their theological worldviews. Once the sister missionaries realize that they are in danger, Sister Paxton’s reaction reflects a broader issue that has resulted in many women distancing themselves from religious communities. While she realizes that she and Sister Barnes are in danger, her missionary training retains a tight grip on her as she maintains an air of politeness and respectability to a man who has indicated he means to harm her.

Social commentary on the potentially anti-feminist nature of religion is also present in several of these films, particularly those dealing with the Catholic church such as The First Omen, Immaculate, and Midnight Mass. The First Omen and Immaculate in particular are both clear responses to the 2022 Dobbs v Jackson Supreme Court Decision which ruled that women do not have a constitutional right to an abortion. Both films, similar to 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, tell the tale of a young woman who is carrying a child whose arrival is anticipated by potentially nefarious forces. However, in a deviation from the 1960’s classic, in both Immaculate and The First Omen, it is a young nun who is pregnant, and in both films, the villains are hyper conservative priests and nuns who deliberately impregnated both women without their knowledge or consent in order to bring religious revival to a declining church via miraculous births (in the case of The First Omen, the literal birth of the anti-Christ, whose presence would unite the church and bring about the end times). Midnight Mass also contains critiques of religious fundamentalism in the character of Bev Keene, who begins the series as merely a rigid and judgmental woman but ends it as a fanatical adherent to the vampire/angel antagonist. Additionally, her vitriol is particularly strong for the local sheriff Hassan Shabazz, who is Muslim. Islamophobia as a result is one of the themes of the show, best shown in one of its many powerful monologues.

In the wake of Dobbs, sexual abuse scandals in both Catholic and Protestant churches, and the rise of religious “nones,” The First Omen, Immaculate, and Midnight Mass all speak to upheavals in American secular and religious life surrounding gender, sexuality, and treatment of minority populations. Some conservative critics of these films (and one tv series), might argue that they are liberal broadsides against conservative Christianity and are best understood as merely shallow propaganda. However, in response to that critique, it should be noted that many protagonists in all of these stories are religious themselves, and in most cases retain their religious identity throughout, despite their breaks with the religious antagonists. They are stories that take religious belief seriously, reflect the contested nature, meaning, and membership of Catholicism, and also speak to the previously unheard survivors of abuse within the church. That perhaps isn’t so surprising. After all, horror as a genre often reflects the fears and anxieties of the culture that produces it, but it also can represent something more.

Horror can serve as a mirror, and what we see might not be a pretty picture, but that dark image can also present an opportunity for hope and change, which is often reflected in the movies themselves, particularly in religious horror. After all, if the devil, demons, and darkness are real and have infected human institutions, which horror movies infer to be true, then God, angels, and the forces of light are real too.

Aaron Ramos is a second-year master’s student at Baylor University. He researches American gender, religious, and imperial history in relation to identity formation among colonized people, primarily in the Philippines.

Aaron Ramos is a second-year master’s student at Baylor University. He researches American gender, religious, and imperial history in relation to identity formation among colonized people, primarily in the Philippines.

David Nanninga is a second-year Doctoral Student of History at Baylor University. His research focuses on American conservatism and neoliberalism in the late 20th century and their relationship to politics, sports, and Christianity.

David Nanninga is a second-year Doctoral Student of History at Baylor University. His research focuses on American conservatism and neoliberalism in the late 20th century and their relationship to politics, sports, and Christianity.