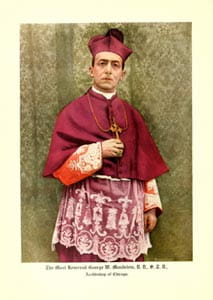

George Mundelein didn't do small. As Chicago's Archbishop (1915-1939), he erected an average of twenty-five buildings every year: churches, schools, and convents. Under Mundelein's leadership, Chicago became home to the world's largest Catholic school system. His seminary campus was larger than many universities. In 1926, Chicago hosted the single largest gathering of Roman Catholics on the North American continent. This was Catholic America's "brick and mortar" era, and Mundelein was God's bricklayer.

George Mundelein didn't do small. As Chicago's Archbishop (1915-1939), he erected an average of twenty-five buildings every year: churches, schools, and convents. Under Mundelein's leadership, Chicago became home to the world's largest Catholic school system. His seminary campus was larger than many universities. In 1926, Chicago hosted the single largest gathering of Roman Catholics on the North American continent. This was Catholic America's "brick and mortar" era, and Mundelein was God's bricklayer.

His own beginnings were modest. Born in 1872 on Manhattan's Lower East Side, he was fourth-generation German-American. Bright and ambitious, he reputedly declined a Naval Academy appointment for the priesthood. At Manhattan College Brother Justin, the president, advised him not to join the New York Archdiocese, lest his talents be wasted in a small parish. He suggested instead becoming a priest in Brooklyn, where the bishop was a close friend.

Career-wise, it proved a good choice. In Rome, Mundelein made a strong impression on the seminary faculty. Ordained in 1895, Brooklyn quickly put his talents to use. The more he did, the more he was given to do. Bishop Charles McDonnell loathed publicity, a problem Mundelein didn't have. Soon he held ten different positions. At age 37, he became an Auxiliary Bishop. A superb fundraiser, he clearly was going places.

Archbishop Giovanni Bonzano, a former professor, was the pope's representative to America, and he helped advance Mundelein's career. In December 1915, Mundelein was named Archbishop of Chicago (at 43, America's youngest.) Allegedly he was originally assigned to Buffalo, but Canada (then fighting Germany) protested a German bishop across the border. So he went to Chicago instead. Nine years later, he was named the first Cardinal in the West.

At the start, he faced a tough situation. The "state of ecclesiastical affairs" in Chicago, a local bishop told him, was "deplorable." Clerical misconduct was widespread, and enforcing discipline was a high priority. Under Mundelein, new priests took a five-year temperance pledge. He created a successful seminary system covering high school through graduate school, and by the 1930s Chicago was ordaining a record fifty men a year.

Before his arrival, the Catholic school system consisted of independent parish institutions with no uniform standards. (In some schools, English wasn't even taught; only Polish, Italian, German, or Bohemian, just to name a few varieties of instruction.) A new school board initiated standard curricula and texts, and mandated instruction in English. In time, Chicago's school system became a national model. The same was true for Catholic Charities. The Catholic Youth Organization (CYO), now with branches nationwide, has its roots in Mundelein's time.

Building, fundraising, and businesslike management characterized this era. On his arrival, Mundelein personally examined the financial records for all 322 parishes. His fundraising attracted attention in Rome, where Chicago's collection for the pope (known as the Peter's Pence) exceeded that of any other American diocese. Hearing that someone bet $10,000 he couldn't speak German, he replied that for $10,000, he'd speak Hebrew.

One executive told Mundelein: "There was a great mistake in making you a Bishop instead of a financier, for in the latter case Mr. Morgan would not be without a rival on Wall Street." Mundelein believed in always "going first class," but not for his own sake. Back in Brooklyn, a businessman once told him: "Now and then, you will meet a man who would give you five dollars in a poor office, but five hundred in a good one."

His love of pageantry was evident at the 28th International Eucharistic Congress, a devotional gathering held in Chicago in 1926. Nearly a million Catholics attended, a new record for America (broken in 1993 by John Paul II at Denver). A children's choir of 62,000 provided music. A special train for now-Cardinal Bonzano, the papal delegate, left New York for Chicago, painted red with his coat of arms. Cynics commented that Mundelein planned to host the Last Judgment in Chicago.

Mundelein biographer Edward Kantowicz called it a "once-in-a-lifetime media event." At the same time, anti-Catholicism was reaching a fever pitch in America. Nationwide, a resurrected Ku Klux Klan targeted Catholics as "un-American" and questioned their right to be here. Part of the reason for Mundelein's pageantry was to show them that Catholics were here to stay.

Theologically, Mundelein was conservative, but socially progressive. A big supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, he became personal friends with FDR and fended off conservative Catholic critics. In Chicago, social action became a keynote of Catholic life. Priests, religious, and laypeople were key supporters of the labor movement, picketed for decent housing, and fought against racism long before these causes became mainstream.