I have a discovery to report.

My current book project focuses on the American empire through history, and its changing relationship to religion. When you study that topic, you inevitably spend a lot of time focusing on the years around 1900, when the country had a ferocious and wide-ranging debate over the propriety of imperial expansion. You can find any number of selections of work from that era, especially by such classic canonical figures as Mark Twain. But I have been working on another figure who was very famous in his day, and a book he wrote that I honestly don’t think has ever received any great scholarly attention. I like to think this is a real find, and I want to share it over the next couple of posts. Today, I’ll give the background, and next time I will get into some detail about the book itself.

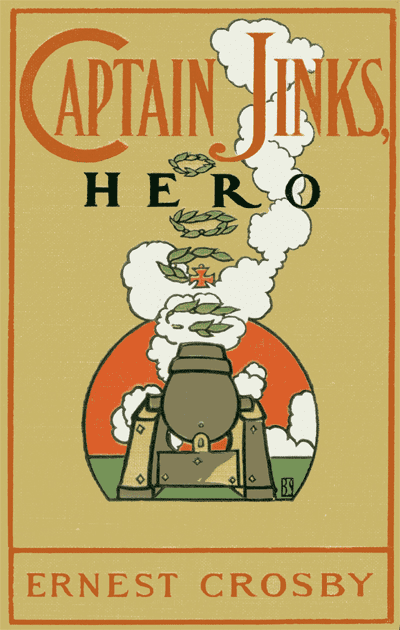

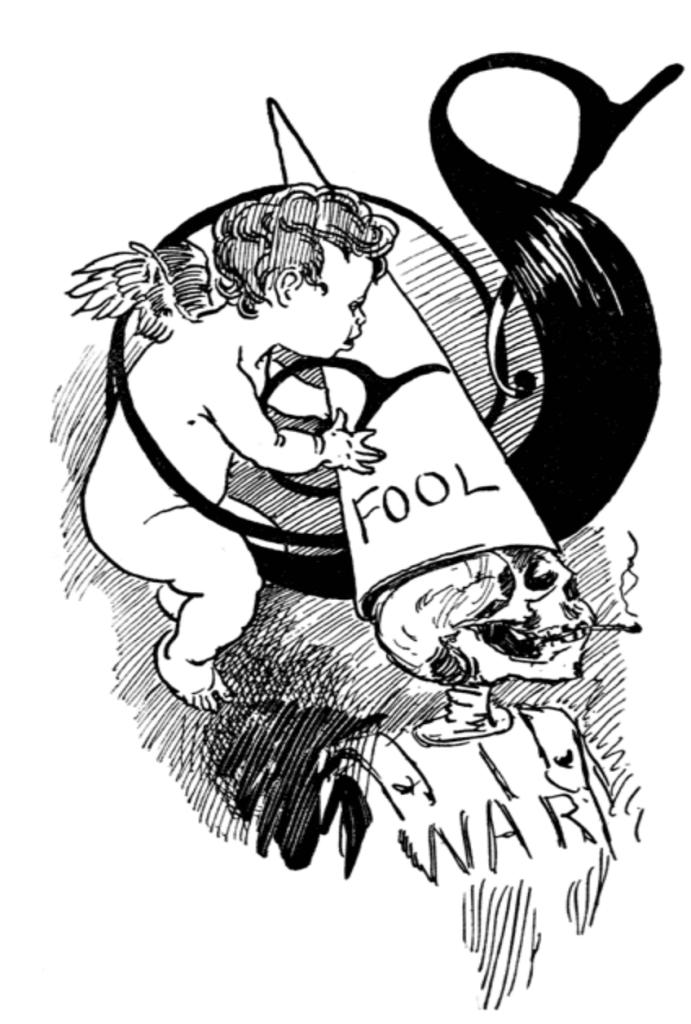

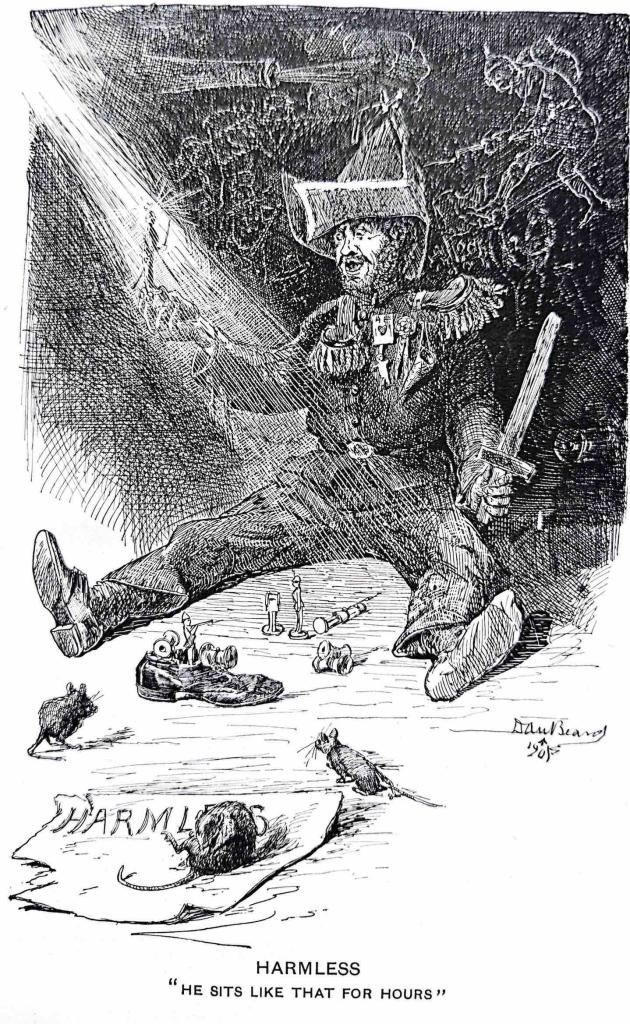

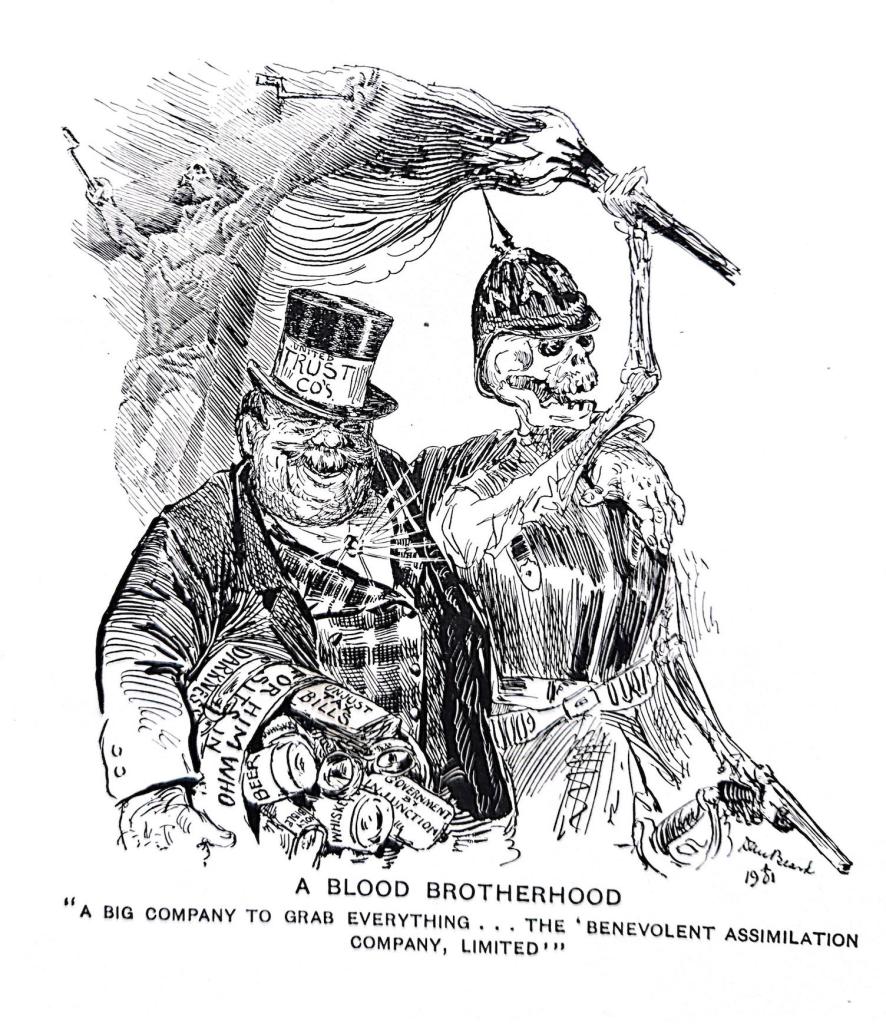

And lest I be accused of being cryptic, the book is by Ernest H. Crosby, and it is called Captain Jinks, Hero (1902). It is a truly angry satire of empire, militarism, Christian missions, war, racism, and masculinity, and it is a terrific resource for studying the era. It is also a great teaching tool. The visuals are always provocative, sometimes brilliant.

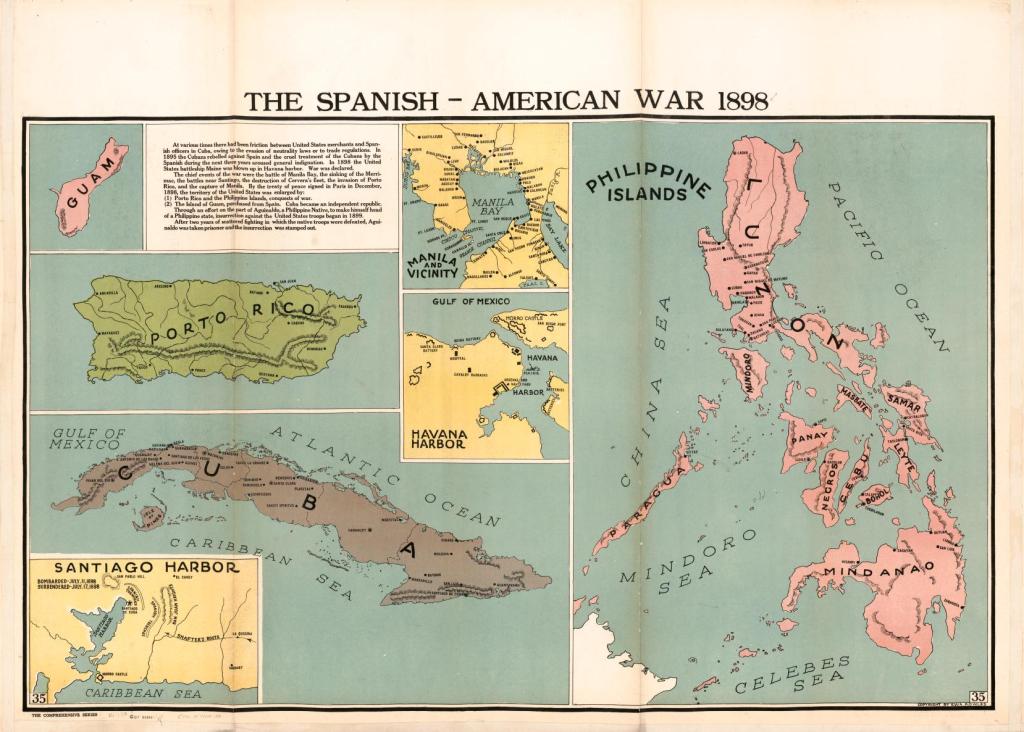

The basic story is familiar enough. In 1898, the US defeated Spain, and occupied such key territories as the Philippines and Cuba. The issue then was what to do with them? Some wanted annexation, followed by what President McKinley called “benevolent assimilation.” Others utterly rejected the idea of the US becoming an empire on the model of the European powers of the day, and they particularly attacked the acquisition of the Philippines. The Anti-Imperialist League became a vital force in American life, attracting key literary and cultural figures, as well as economic titans such as Andrew Carnegie. The league gained broad public support as US forces got ever deeper engaged in a war against Philippine resistance forces, a conflict that to modern eyes looks like an accurate first draft of Vietnam. As in Vietnam, a lot of the fighting happened in the boondocks, the boonies – which is the original Tagalog word that the US forces brought home with them in 1902.

Making matters even worse, after all the bloodshed in the Philippine War, the US military was then engaged in the suppression of the Boxer revolt in China, and again, Western forces were widely condemned for their brutality.

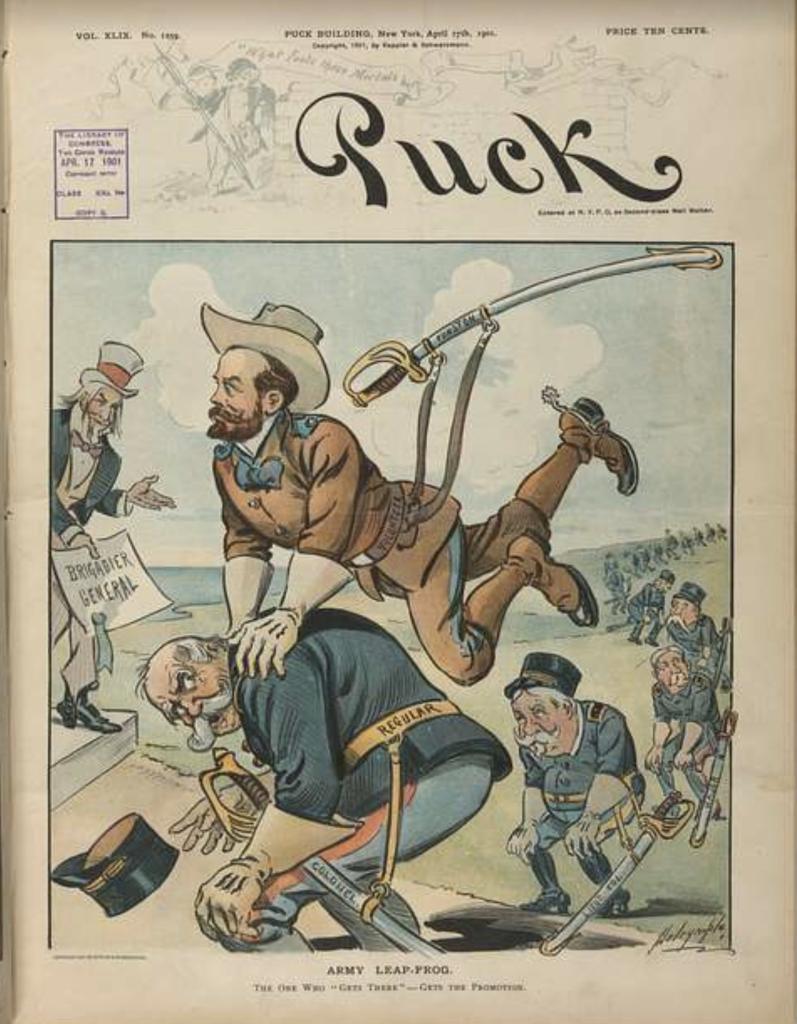

One controversial figure in the Philippine debates was General Frederick Funston, whose name survives today in the “Fort Funston” that is such a popular recreation area in San Francisco. In the Philippines, “Fighting Fred” Funston succeeded in capturing the rebel leader Aguinaldo through a shrewd combination of intelligence work and deceit, using forged documents and disguised loyal Filipino soldiers. That achievement did much to end the war. However, Funston’s tactics were bitterly criticized by anti-imperialists, and Mark Twain published a much anthologized “Defense of General Funston” which complained that Funston had flouted rules that “even the degraded Spanish friars had respected.” In turn, Funston himself publicly denounced anti-imperialists, even to the point of angering President Theodore Roosevelt. He memorably advocated “impromptu domestic hanging” for anti-war activists like Ernest Crosby, who “should be dragged out of their homes and lynched.”

One controversial figure in the Philippine debates was General Frederick Funston, whose name survives today in the “Fort Funston” that is such a popular recreation area in San Francisco. In the Philippines, “Fighting Fred” Funston succeeded in capturing the rebel leader Aguinaldo through a shrewd combination of intelligence work and deceit, using forged documents and disguised loyal Filipino soldiers. That achievement did much to end the war. However, Funston’s tactics were bitterly criticized by anti-imperialists, and Mark Twain published a much anthologized “Defense of General Funston” which complained that Funston had flouted rules that “even the degraded Spanish friars had respected.” In turn, Funston himself publicly denounced anti-imperialists, even to the point of angering President Theodore Roosevelt. He memorably advocated “impromptu domestic hanging” for anti-war activists like Ernest Crosby, who “should be dragged out of their homes and lynched.”

In the standard histories of the imperialism debates, Funston clearly stands out as one of the expansionist arch-villains of the era. San Franciscans liked him because of his decisive role in maintaining order during the great earthquake of 1906, and called him “the man who saved the city.” Hence the dedication of that fort a few years later.

One of the most powerful writers in the Anti-Imperialist cause was Ernest Crosby, a very radical thinker of the day who was a primary American interpreter of Leo Tolstoy, a leading pacifist and anti-capitalist, a vegetarian and anti-racist. Crosby made Funston the subject of a crushing satirical novel, Captain Jinks, Hero, which follows the career of a heroic American warrior of the day. To give some idea of the book’s tone, [SPOILER!] it ends with Jinks/Funston’s lifelong commitment to an asylum as a gibbering maniac who only enjoys playing with his toy soldiers.

The title requires an explanation. The character name Captain Jinks goes back to an Antebellum song that goes as follows:

I am Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines,

I often live beyond my means,

I sport young ladies in their teens,

To cut a swell in the army….

I join’d my corps when twenty-one,

Of course I thought it capital fun;

When the enemy came, then off I run,

I wasn’t cut out for the army.

The title is jokey, as the Horse Marines are proverbial for not existing, and anyone who thinks they do (or did) knows nothing about the military. Everyone knew the song: Laura Ingalls Wilder’s father loved to play the song on his fiddle. (I owe this reference to my learned friend, Kathryn Hume, to whom many thanks are due).

But the name gained a new currency in 1901 when the hugely popular Broadway writer Clyde Fitch scored a triumph with his play, Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, which first made a star of Ethel Barrymore. In any case, the name “Captain Jinks” was firmly established in New York popular culture as a less-than-serious dilettante soldier, and dare I suggest that Ernest Crosby was cashing in on it by suggesting some kind of connection with his novel.

The book was illustrated extensively throughout by Dan Beard, a famous radical artist and caricaturist of the day, who worked closely with Mark Twain. Like Crosby, Beard was a devotee of the reformer Henry George.

But here is the point. We often see a battery of visuals about this era, that I have cited myself at this blog. But both the core arguments about imperialism, and many, many, visuals are collected superbly in Captain Jinks Hero, which basically nobody ever cites. One of the rare modern exceptions is Richard E. Welch’s Response to Imperialism (1979) which mentions Crosby’s book as “an effective parody of Funston’s career.” However, even Welch only devotes half a paragraph to the work.

But here is the point. We often see a battery of visuals about this era, that I have cited myself at this blog. But both the core arguments about imperialism, and many, many, visuals are collected superbly in Captain Jinks Hero, which basically nobody ever cites. One of the rare modern exceptions is Richard E. Welch’s Response to Imperialism (1979) which mentions Crosby’s book as “an effective parody of Funston’s career.” However, even Welch only devotes half a paragraph to the work.

The book deserves a lot more attention. Watch this space for my next post.

REFERENCES:

Not many scholars in recent years refer to the novel in any detail, and only rarely to Crosby himself. Already in 1972, Crosby was regarded as a “forgotten” figure: see Perry E. Gianakos, “Ernest Howard Crosby: A Forgotten Tolstoyan Anti-Militarist And Anti-Imperialist,” American Studies 13.1(1972): 11-29. There are brief references in Philip S. Foner, The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism Vol. 2: 1898–1902 (NYU Press, 1972); and more substantially in Cynthia Wachwell, War No More: The Antiwar Impulse in American Literature, 1861–1914 (Louisiana State University Press 2010).

Such “forgetting” arguably made sense in the 1970s, but in light of the incredible modern boom in academic studies of the American empire and its foes, the oblivion is unpardonable.