In pretty much any period I write about, I try to use cartoons and caricatures wherever possible because they offer such a wealth of material that would be so hard to extract from contemporary prose accounts. I offer a couple of examples today, together with an appeal for any similar items that people might be able to think about.

I have been working on the intersection of missions and empire in US history, and generally, pro-empire people were very happy to use missionary rhetoric in order to justify expansionist ventures. But there were some nuances. When anyone studies the time of the Spanish-American War in 1898, with all its consequences for American overseas empire, they inevitably use the very rich resources offered by cartoonists such as Louis Dalrymple, commonly working in the satirical magazine Puck. Dalrymple was a phenomenally important figure in shaping US public opinion in this era: just see the superb collection of cartoons you can find on many, many aspects of the politics and society of the years around 1900. His personal life, incidentally, was grim: he died at age 39 after a period diagnosed as insane, as a consequence of paresis presumably arising from syphilis.

Dalrymple was a strong and consistent supporter of US imperial dreams. His cartoons condemned the savagery of Spanish rule before the war, and after victory they regularly feature a stern Uncle Sam striving to regulate the bad behavior of the obstreperous dark-skinned children who have unwillingly joined the great American family. Ideally, the peoples of the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Hawaii with stern discipline might somehow be brought to the improved status of conquered peoples within the US itself, such as the Latinos of California or the Southwest, or Alaska’s Natives. The US, it was suggested, would bring education, literacy, and civilization. Dalrymple condemns the naive anti-imperialists who urge withdrawal from the occupied lands, a proposal that would mock the casualties the nation had suffered in gaining them.

That is all straightforward, but Dalrymple departs from the script in one major way, in that he has no time whatever for Christian missionaries, or the claim that American expansion would open the door to the growth of Christianity in new territories. In two cartoons in particular, he offers a savage critique of such claims. They eminently repay careful attention.

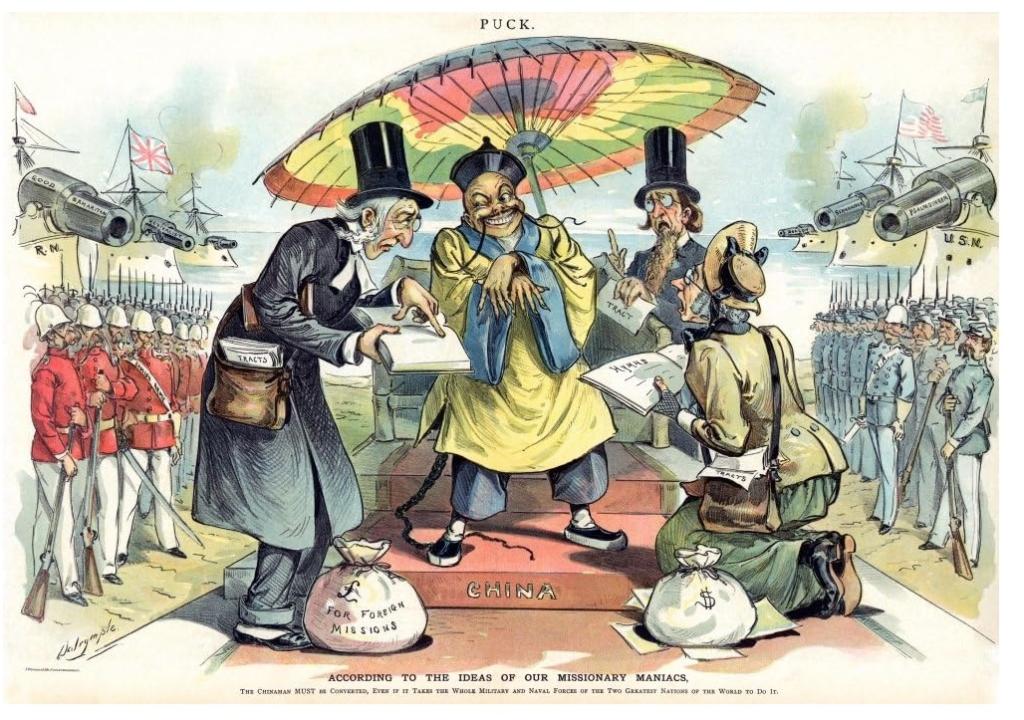

In 1895, Puck published his powerful caricature of a stereotyped Chinese mandarin being browbeaten by three earnest Western missionaries, who carry heavy money bags assigned “For Foreign Missions.”. In the background, we see the very well-armed British and US fleets with their mass armies. The warships’ guns bear labels such as “Good Samaritan,” “Revivalist,” “Psalm-Singer,” “Sermonizer,”, and “Deacon.” The caption informs us that “According to the ideas of our missionary maniacs, the Chinaman must be converted, even if it takes the whole military and naval forces of the two greatest nations of the world to do it.”

In 1900, Puck offered “Our foreign missions;– an embarrassment of riches for the heathen,” which shows a pagan African hearing the diverse pleas of the various American sects competing for his loyalty. (And unquestionably, that is a racist stereotype quite as ugly as that of the Chinese Mandarin). The main temptation offered is a basket of cheap goods, including Western clothes and a doll. The image is in part a mockery of those Christian denominations and their alleged weaknesses, but it also demonstrates Dalrymple’s contempt for missions in general.

The parodies of the various Christian denominations are effective and often funny, and I leave readers to follow through on them as they wish. The Broad Range Episcopalian: “Don’t interfere with your religion.” Methodists: “Noisy, but sure.” And the Unitarian on the far left is a very dapper figure, offering “Easy – all the modern conveniences.” He is a traveling salesman as much as a missionary.

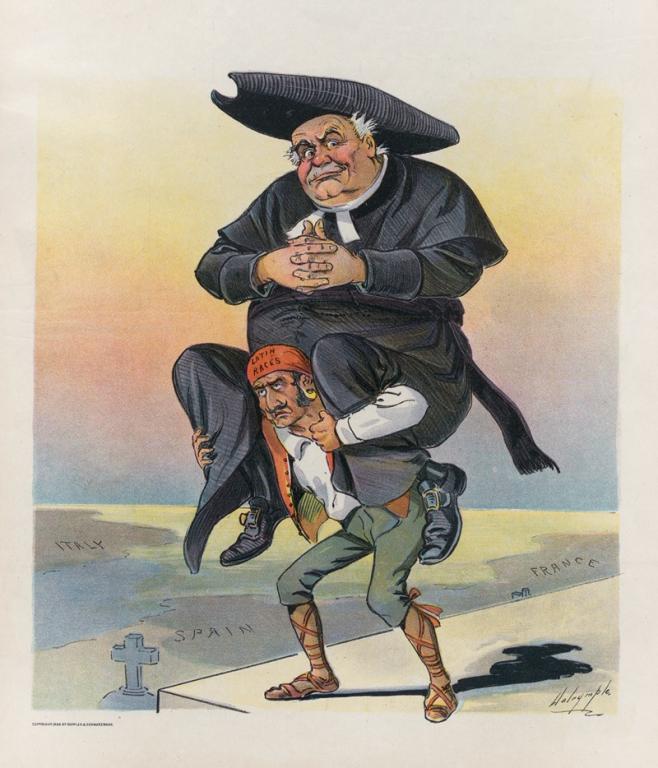

I would see this as illustrating anti-clerical or anti-religious views, not far from those of Mark Twain. Here again, is Dalrymple’s “The Burden of the Latin Races.”

But the question then arises: how unusual was Dalrymple in these anti-missionary approaches?

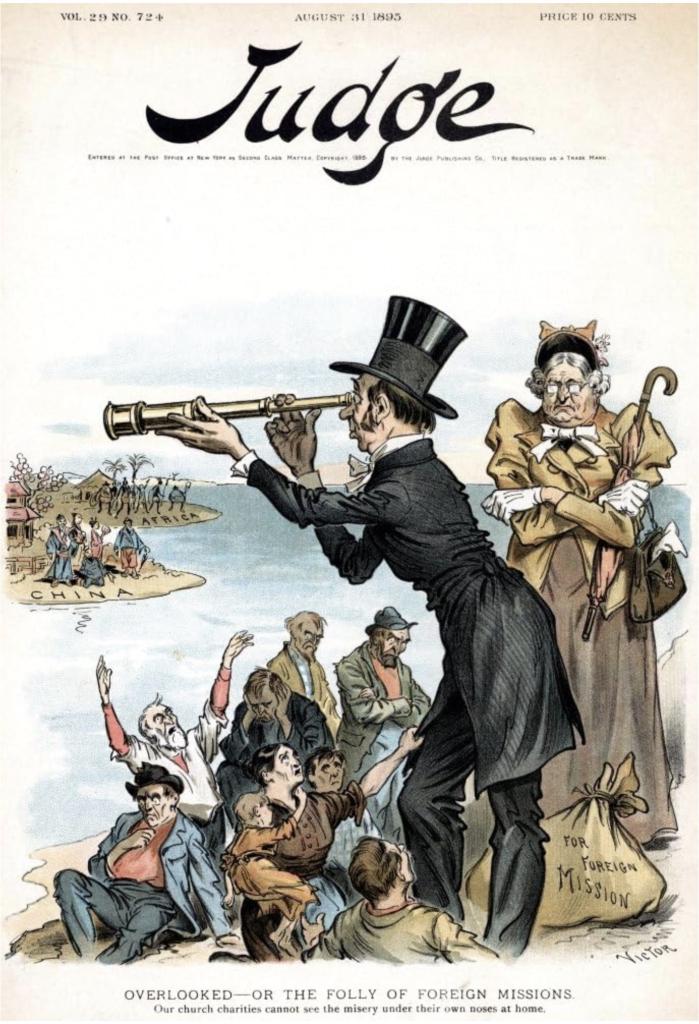

I know of some parallels and precedents. The “embarrassment of riches” has a strong contemporary parallel in this one from 1898, which I can’t reproduce here for rights reasons. There is also an American one from 1895, “Overlooked,” which attacks the callous stupidity of missionaries who can’t see the desperate poverty in their own land, but are so anxious to take their humanitarian efforts overseas. That was very much the same point that Charles Dickens had made in his 1853 novel Bleak House, about the dreadful Mrs Jellyby, who was obsessed with funding outrageous ventures in distant corners of empire – “the natives of Borrioboola-Gha, on the left bank of the Niger” – while grievously neglecting her own home and family.

We also note the gender element in this critique. Both in “Overlooked” and in Dalrymple’s attack on “Missionary Maniacs,” witness the strong role attributed to women as driving forces in the missionary venture. The women are however portrayed very grimly, as stern, domineering, prissy, and puritanical stereotypes. Again, think Mrs. Jellyby.

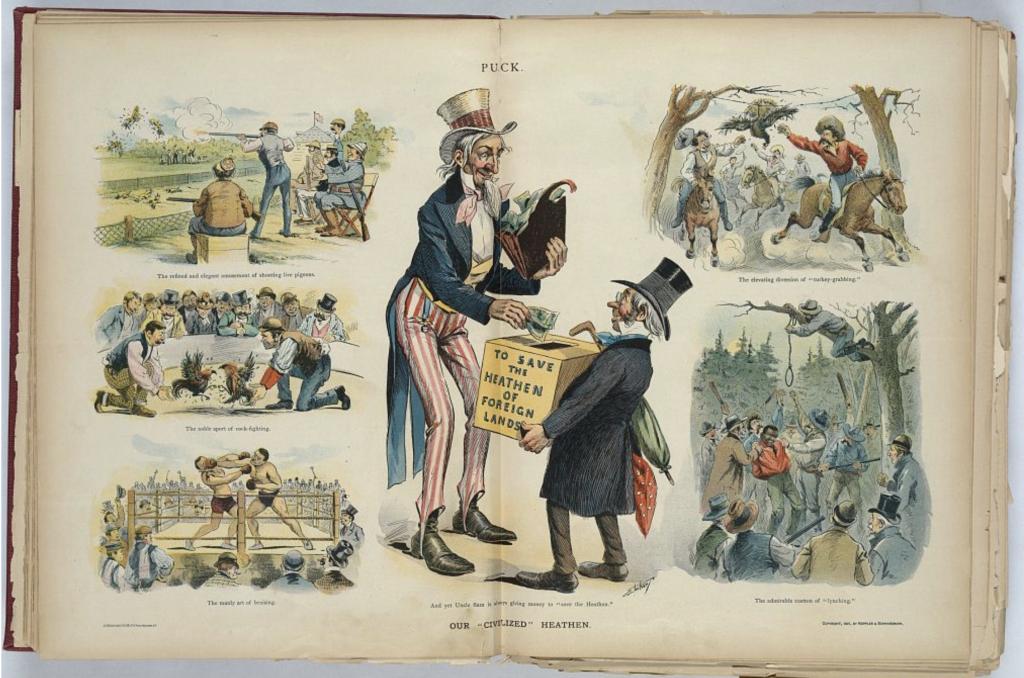

Another familiar trope in such cartoons was the arrogant superiority that Westerners claimed to the outside world, all evidence to the contrary. Here for instance is another Puck cartoon from 1897, showing Uncle Sam donating generously to foreign missions, despite all the bloody pastimes in his own country – systematic brutality, cruelty to animals, not to mention lynching.

These late nineteenth-century offerings actually have a lengthy English prehistory, which the Americans certainly would have known well.

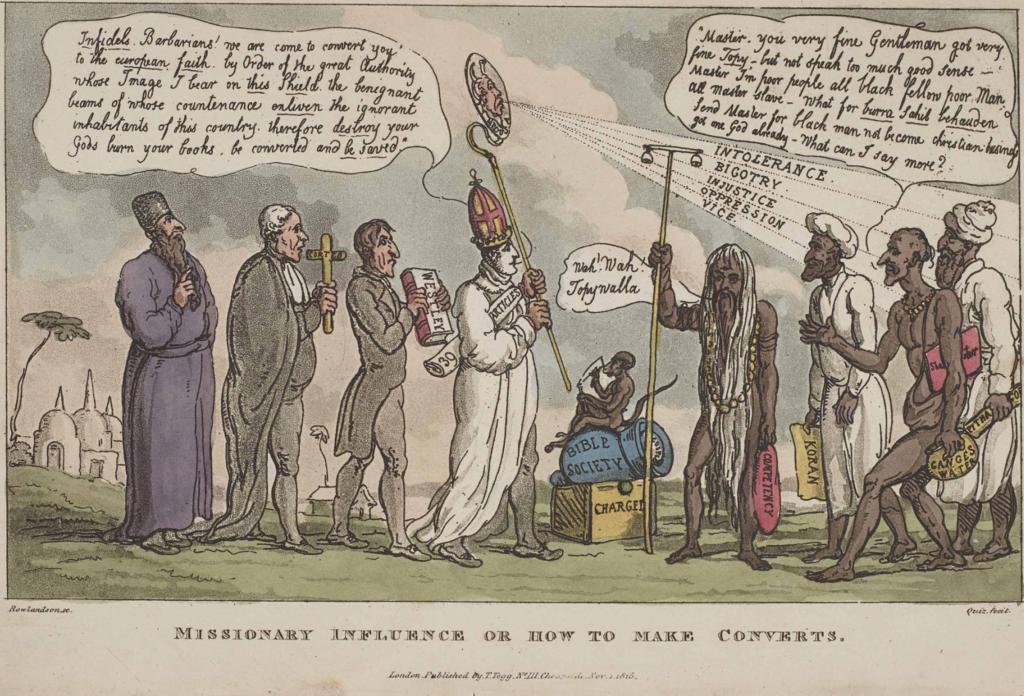

England’s Thomas Rowlandson did a classic anti-missionary piece back in 1816, arguably the perfect example of its kind. By way of chronology, the idea of foreign missions was very much in the air of Protestant societies around this time. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) dates to 1810, and more to the point, in 1814, the Church of England created the first of its overseas bishops for imperial territories, with the new see of Calcutta. That Calcutta venture is clearly what Rowlandson is referencing in his savage satire. He shows British missionaries trying to convert Indian heathens, who emerge from the debate very well indeed.

The missionary bishop carries a shield symbolizing a “great authority whose image I bear … the benignant beams of whose countenance enliven the ignorant inhabitants of this country.” The face is that of the then King George III, but his image is labeled MEDUSA, who in Classical mythology was so hideous that her face turned to stone anyone who witnessed it. That face issues forth deadly rays, labeled “intolerance, bigotry, injustice, oppression, vice.” Just what those native peoples need!

The political background needs some explanation. England in 1816 was under a very repressive and reactionary Tory administration that operated in intimate alliance with the Anglican church. One “heathen” warns his friends to watch out: “Wah! Wah! Torywalla” (that is, Tory guy). The other acknowledges the missionary is “very fine gentleman … very fine Tory – but not speak too much good sense.” Does he not realize he is talking to poor people and slaves? Why doesn’t the Brit become a Christian himself? As for the native, “Got one god already – what can say more?”

As the reader is meant to ask: sorry, who in this exchange is the ignorant savage?

Can people point me to other similar materials, whether in the 1890s or earlier? Assistance will be gratefully acknowledged!