This post is a tribute to the life and teaching of Kristen Todd, PhD, the late professor of music history at Oklahoma Baptist University. Dr. Todd passed away in 2014 after a fifteen-year career of teaching and mentorship at OBU.

There’s not much I remember from my undergraduate days at Oklahoma Baptist University. But I do remember one morning in the early fall of 2008, where a large class met in a lecture hall in the south side of Raley Chapel, a towering structure with a majestic, stone columned entryway, brightly-lit stained glass windows with symbols calling to mind heroes of the free church tradition, and a prominent white steeple that could be seen all the way from I-40 on the other side of town. Raley was the closest thing to a cathedral most of us Baptist students had. On this particular morning, we gathered for another lecture from our Arts and Ideas professor, Dr. Kristen Todd.

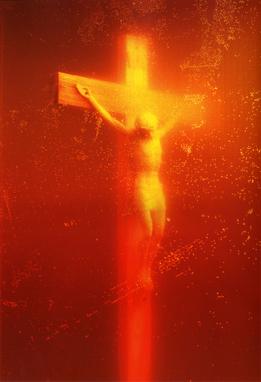

We were talking about the relationship between art and faith. As part of our discussion, Dr. Todd posted an image on the projector screen. It was a photograph of Christ on the cross, glowing brilliantly in shades of yellow and orange and surrounded by hues of deep crimson and blood red. We talked about the beauty of the image, the way it evoked feelings of transcendence and mystery, blood and violence, and a sort of serenity. And then she revealed the medium by which the artist captured such a enigmatic and somber image. The crucifix was a cheap plastic figurine of Christ, one that could be bought for a few bucks at a gift shop or bodega. And the crucifix was submerged in the artist’s own bodily fluids—more specifically, it was dunked in piss.

When Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ emerged on the art world scene, its existence provoked the ire of the American right almost immediately. In fact, the work kickstarted a major wave of culture warring in the late 1980s and early 90s when it was discovered that Serrano’s public exhibition, which included Piss Christ, was funded with taxpayer dollars through the National Endowment for the Arts. The American Family Association, a right-wing Christian political organization, caught wind of Serrano’s exhibit in April 1989, drawing the attention of Republican senators and inflaming a nationwide backlash against publicly funded art deemed offensive, indecent, or blasphemous. Senators Jesse Helms and Al D’Amato became standard bearers against Serrano and the NEA, tearing an image of the photograph on the Senate floor and calling Serrano’s work “a deplorable, despicable display of vulgarity.” Texas Republican Dick Armey reportedly decried the work as “a blatant and ruthless mockery of the Christian religion.”

When Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ emerged on the art world scene, its existence provoked the ire of the American right almost immediately. In fact, the work kickstarted a major wave of culture warring in the late 1980s and early 90s when it was discovered that Serrano’s public exhibition, which included Piss Christ, was funded with taxpayer dollars through the National Endowment for the Arts. The American Family Association, a right-wing Christian political organization, caught wind of Serrano’s exhibit in April 1989, drawing the attention of Republican senators and inflaming a nationwide backlash against publicly funded art deemed offensive, indecent, or blasphemous. Senators Jesse Helms and Al D’Amato became standard bearers against Serrano and the NEA, tearing an image of the photograph on the Senate floor and calling Serrano’s work “a deplorable, despicable display of vulgarity.” Texas Republican Dick Armey reportedly decried the work as “a blatant and ruthless mockery of the Christian religion.”

Bearing False Witness

Over the course of the evangelical culture wars, Serrano’s Piss Christ has become something of a shorthand for blasphemy. Shortly after the NEA’s funding policies were upheld in a congressional vote, Richard Land, then leader of the SBC’s Christian Life Commission, decried the decision as continuing to fund works which are “sacrilegious or morally repugnant.” A 2009 article on art and religion in Christianity Today referred to the work as “transgressive and sensationalist.” More recently, Carl Trueman has taken aim at Serrano as a leading example of one who engages in “deathworks,” a term borrowed from Philip Rieff. In his recent Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, Trueman writes that “Serrano is not simply mocking the sacred order in this work of art; he had turned it into something dirty, disgusting and vile.”

My undergraduate arts professor would disagree. In fact, she did. Our time spent in the chapel of a Southern Baptist university, contemplating the handheld figurine of Christ floating in urine, was intended by our professor to invite introspection, investigation, and interpretation. We asked questions of the piece and of its creator. Dr. Todd helped by giving us some context. She noted that the piece was intended to make a statement not about the profanity of Christ, but about the commodification of Christ, the materialism of the Church, and the exploitative failures of its members. Christians, in some sense, defile the crucified Christ by the way we objectify and buy and sell the holy.

When Piss Christ came came under scrutiny, some evangelical art scholars were quick to complicate the issue. The right-wing backlash could, some argued, have unforeseen negative consequences for the public funding of Christian art. In a 1989 Christianity Today piece on the controversy, Ed Knippers, a leading member of the organization Christians in Visual Arts (CIVA), argued that Christians needed to establish private funding for “Christian artists who make a powerful statement within the light of a Christian worldview, and make it of such a high quality that some of the major museums would be glad to have it.” Similarly, CIVA president and Calvin College professor Ed Boeve chided evangelicals who “march and hand out pamphlets, yet have not supported the arts themselves.” “If Christians are offended by Serrano’s art,” Boeve continued, “I wonder how much of their budget they have spent to support Christian artists.”

Evangelical artists were more willing than Republican politicians to consider the various problems inherent in the public censorship of art, but they were also quick to assert that the answer was putting more Christian artists and better Christian art in the public eye. The complication almost everyone was unwilling to grapple with, however, was that Andres Serrano was himself a Christian artist.

Serrano Speaks

In interviews on his work, and particularly on the legacy of Piss Christ, Serrano has been quick to defend himself as a religious individual grappling with his Christian faith. In a 2014 interview with The Huffington Post, Serrano was asked about the message his photograph was meant to convey.

The only message is that I’m a Christian artist making a religious work of art based on my relationship with Christ and The Church. The crucifix is a symbol that has lost its true meaning; the horror of what occurred. It represents the crucifixion of a man who was tortured, humiliated and left to die on a cross for several hours. In that time, Christ not only bled to dead, he probably saw all his bodily functions and fluids come out of him. So if “Piss Christ” upsets people, maybe this is so because it is bringing the symbol closer to its original meaning.

In another interview with El País, Serrano stated that when he created the photo, his own personal interpretation was to humanize the religious iconography. “I didn’t think it was blasphemy or anything like that. A crucifix like this one has become so banal, it is even used as a fashion accessory and for many people, it doesn’t mean all that much. But when you spend so many hours crucified, everything comes out, piss and the shit, everything. So, if it offends you, you should think about what it represents, which is the horrible way in which Christ was murdered.”

Here, Serrano points to the reality that, while many traditional depictions of the crucifixion have sanitized the event, the historical reality was visually one of “horror.” Serrano, in his own way, brings to bear the most base and scandalous truths about the incarnation. For Serrano, being offended by the grotesqueness of the cross is a natural reaction. That we are not says more about us than it does about his image.

On the subject of his own faith, Serrano considers himself anything but anti-Christian. “I was brought up in Christianity, I am part of the church, and I feel connected to a long tradition of Christian artists working with the faith’s symbols,” he says. “At my confirmation, the nuns told me that I had become a soldier of God. Even though I stopped going to church for religious reasons, and now only go when I’m in Europe for artistic reasons, I’m still a soldier of Christ.”

Serrano sees his own work as intended to draw attention and debate—“if the meaning is that obvious, it is not art anymore, it becomes propaganda. The crucifix is simply a common object, that we take for granted. It is minimal.” However, he is quick to qualify that as a Christian artist, he has “no sympathy for blasphemy.”

Charity and the Ethical Dimension of Interpretation

Serrano’s own statements contribute to the paradox of of the artistic endeavor. Images and symbols, like texts, are multivalent, they invite interpretation. But what are the boundaries of interpretation? Does the author or creator determine, or at least contribute to, how we should receive these artifacts? And what role does charity and openness play in enlarging—or restricting—those boundaries?

At the very least, I think Christians’ failure to reckon with Serrano as a Christian dialogue partner has been a failure to play by their own rules and take authorial intent as a determinative factor in interpretation. Authorial intent is, of course, something that evangelicals traditionally prioritize when coming to texts, especially scripture. Seven years before Serrano’s infamous image debuted, Gordon Fee and Doug Stuart published their now-ubiquitous How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, the standard introduction to hermeneutics and exegesis. Here, they wrote that the “only proper control” for interpreting the Bible was “to be found in the original intent of the biblical text.” More recently, Andreas Köstenberger writes in his Invitation to Biblical Interpretation that there is “an important ethical dimension in interpretation. We should engage in interpretation responsibly, displaying respect for the text and its author. There is no excuse for interpretive arrogance that elevates the reader above text and author.”

When the controversy over the “table setting” at the Olympics opening ceremony sprang up, I immediately thought of Serrano. Evangelicals were quick to pounce on what they thought was a defacing of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, as Joey Cochran catalogued at Anxious Bench at the end of the summer. I was particularly struck by Joey’s observation that evangelicals strategically let go of the authorial intent rope, even after the Olympics artistic director Thomas Jolly asserted Da Vinci wasn’t in view. There are layers to this—the rapidity of the backlash, the fact that Da Vinci’s painting isn’t a historical rendering but is itself a culturally-circumscribed Italian reimagining of the Passover—but I don’t want to go there for now.

When I was reading the evangelical diatribes against the Olympics ceremony, I was reminded of Serrano. But I was also reminded of Dr. Kristen Todd, a professor at a conservative Southern Baptist university, and I was thankful. I was grateful that all those years ago, she had helped inoculate me against the proclivity to immediate outrage and offense. In that one class, in that one instant, she invited me to think Christianly about this curious photograph and what it might be trying to say. Like Andreas Köstenberger, she asked us to interpret ethically and responsibly, displaying respect for the piece and its author. She compelled us to think about the relationship between the Church, power, and capital. Perhaps without ever knowing it, she called myself and others to step outside the rage machine, to defect rather than be conscripted in the culture war. Dr. Todd wanted us to be interested and sympathetic observers of Christ, even a Christ drenched in the most disreputable elements of human existence. By doing so, we risked losing the chance to be warriors in the battle for American public decency but, in the words of Andres Serrano, we could gain the opportunity to become “soldiers of Christ.”