One of the disconcerting things about researching recent history is that my historical subjects—many of whom I’ve met (and interviewed) in real life—sometimes die. The latest is Bill Pannell, an important figure in the evangelical left who died last week at the age of 95. I found him to be a kind and impeccably dressed prophet when I encountered him (along with Donald Dayton and Richard Mouw) on a dissertation research trip to Pasadena, California. As I recall, he had just retired from many decades of teaching at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Pannell became a minor evangelical celebrity in the 1960s. In his role as a columnist for Freedom Now, a magazine that tried to get white evangelicals to back the civil rights movement, Pannell narrated what it was like to grow up in the religious heartland. As a child in southern Michigan, he had joined a white evangelical church and then attended Fort Wayne Bible College. While he enjoyed warm piety and close friendships in these institutions, he also suffered the limits of being “a colored stranger” in white contexts. He felt the “anxiety and agony of being an alien in one’s own land.”

Pannell became a minor evangelical celebrity in the 1960s. In his role as a columnist for Freedom Now, a magazine that tried to get white evangelicals to back the civil rights movement, Pannell narrated what it was like to grow up in the religious heartland. As a child in southern Michigan, he had joined a white evangelical church and then attended Fort Wayne Bible College. While he enjoyed warm piety and close friendships in these institutions, he also suffered the limits of being “a colored stranger” in white contexts. He felt the “anxiety and agony of being an alien in one’s own land.”

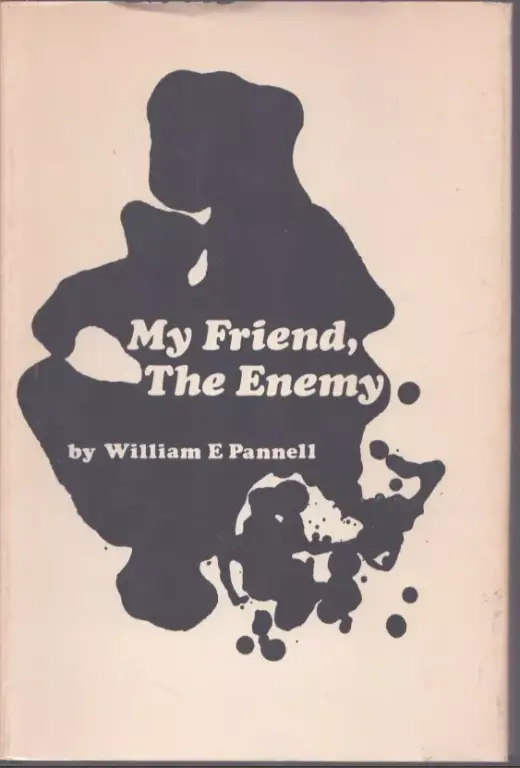

His first book, the immensely popular 1968 book My Friend, the Enemy, pursued the same theme. Pannell asserted that “this conservative brand of Christianity perpetuates the myth of white supremacy. It tends also to associate Christianity with American patriotism, free enterprise, and the Republican party.” The white evangelical was “my friend, the enemy.” He worshiped the same God, Pannell said, opposed the KKK, decried violence, supported the Constitution, and encouraged Black voting rights. At the same time, the white evangelical was likely to denounce racial agitators and maybe even “agree it is best that I not live in his city’s limits.”

Nevertheless, Pannell remained an evangelical. Despite being “more grateful to SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] than to Southern Baptists,” Pannell wanted to encourage action toward racial justice. Alongside Black evangelical colleagues like John Perkins and Tom Skinner, he resisted growing pressure in the late 1960s to establish separate Black institutions. He contended that too many separate institutions would deviate from the example of the interracial New Testament church—and from the early civil rights movement, which disavowed Black separatism. Pannell urged disgruntled Black evangelicals suffering under both subtle and overt forms of discrimination to stay the course. The true path to racial justice, he maintained, was the creation of an interracial community that together worshipped God. He wanted to help build a “beloved community.”

Nevertheless, Pannell remained an evangelical. Despite being “more grateful to SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] than to Southern Baptists,” Pannell wanted to encourage action toward racial justice. Alongside Black evangelical colleagues like John Perkins and Tom Skinner, he resisted growing pressure in the late 1960s to establish separate Black institutions. He contended that too many separate institutions would deviate from the example of the interracial New Testament church—and from the early civil rights movement, which disavowed Black separatism. Pannell urged disgruntled Black evangelicals suffering under both subtle and overt forms of discrimination to stay the course. The true path to racial justice, he maintained, was the creation of an interracial community that together worshipped God. He wanted to help build a “beloved community.”

But the tools of white evangelicalism weren’t sufficient. As the 1960s wore on, Pannell and other Black evangelicals began to doubt the efficacy of personal salvation in sparking social change. Many of the pious evangelicals that Freedom Now contributors knew best—Baptists in the South, people in their congregations, even their own parents—remained flagrantly racist. How, asked a disparate but growing group of younger evangelicals, could their parents’ generation sing about Black people being precious in God’s sight, yet fail to condemn outrages perpetrated by police? How could they decry the March on Washington as a “mob spectacle”? How could they condemn interracial marriage?

Perhaps white evangelicals had it backward. Perhaps a focus on social justice might spark more effective evangelism. After all, their efforts to convert Black Americans—most of whom, of course, were already Christians—were failing miserably as they encountered despair and rage. At a Baptist conference on race and religion in 1968, Pannell told attendees that “old style evangelism is inadequate to meet the needs of the ghetto; we must meet human needs if we are to genuinely meet religious needs.” Converting souls by itself could not sufficiently level systemic inequalities.

This critique made Pannell a perfect fit for an emerging progressive strain of evangelicalism. When the evangelical left convened in Chicago in 1973, Bill Pannell was there. So were an impressive number of other individuals associated with Freedom Now, including editor John Alexander; William Bentley, who became president of the National Black Evangelical Association; community developer John Perkins; Ruth Bentley, who had just earned a Ph.D. from the University of Alabama; Clarence Hilliard, pastor of the interracial Circle Church in Chicago; and Wyn Wright and Ron Potter of Voice of Calvary. These individuals were instrumental in constructing the Chicago Declaration’s opening confession about race in America. They wrote, “Although the Lord calls us to defend the social and economic rights of the poor and oppressed, we have mostly remained silent. We deplore the historic involvement of the church in America with racism and the conspicuous responsibility of the evangelical community for perpetuating the personal attitudes and institutional structures that have divided the body of Christ along color lines.”

At that moment in the early 1970s, Pannell was optimistic. “A new breed of evangelicals” had arrived, and the time for “significant breakthroughs was now.” So he remained part of a movement in which he also felt like an outsider—and did so for the next half century.

Sadly, not much changed. In 2021, a year after the killing of George Floyd, Pannell felt compelled to republish My Friend, the Enemy. Daniel Silliman put it well last week in his Christianity Today obituary: “Pannell couldn’t help but notice that while the names and dates had changed, the problem persisted. And white evangelicals still seemed captive to a culture deeply invested in ignoring the issue.” His own religious tradition, said Pannell not long before his death, needed to be “born again.”