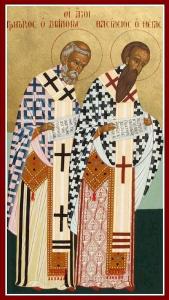

Basil of Caesarea is often praised as a champion of the Holy Spirit, defending his divinity against the Macedonians and the Eunomians in his On the Holy Spirit. And my students gleaned as much, as we read the text together a few weeks ago. But this was not the only reading under discussion that day—students also read Gregory of Nazianzus’ Epistle 58. In this letter to Basil, Gregory records an embarrassing situation that arose during a dinner party—after someone praised Basil’s virtues, another stood up and exclaimed “Basil is wrongly praised for orthodoxy—and Gregory wrongly, as well … He will not speak the truth frankly, but bathes our ears in language more political than pious” (Gregory Epistle 58). What is the truth that he is unwilling to declare? That the Holy Spirit is God. Near the end of the text, Gregory passive aggressively asks Basil: “how far should we come forward in speaking of the Spirit as God? What expressions should we use? To what extent should we ‘manage’ our speech? We need to have a firm front against those who criticize us!” (Gregory Epistle 58). By pairing this epistle with Basil’s work, my students were able to see that despite Basil applying most every category of divinity that he can to the Spirit, there is a glaring omission: he refuses to straightforwardly call the Holy Spirit God. Why does he do this? Are we wrong to praise Basil for orthodoxy?

Teaching Historical Theology

At the Conference on Faith and History last week, I had the opportunity to discuss pedagogy with several of my Anxious Bench colleagues, Ansley Quiros and Daniel Williams. During our conversation, it became abundantly clear that teaching religious history takes on different forms, depending on your aims, audience, and the content under discussion—though, the common setting of our secular and Christian universities in the Bible belt provided some interesting commonalities.

The main class that I reflected on is called “Christian Thought, which is essentially an introduction to historical theology. If you are uninitiated, historical theology is the study of God through the lens of historical figures. Thus, one must pay particular attention to both theological ideas and the historical milieu which shapes them. As Ellen Scully and Anthony Briggman put it,

“In contrast to confessional, constructive, and systematic methods, the method of historical theology is essentially historical, defined by a commitment to consider and elucidate the Christian tradition in all of its variety and complexity and in light of its full historical context. In contrast to sociocultural methods, the method of historical theology is essentially theological, defined by a commitment to consider and understand the full complexity of the abstract thought world that stands behind the textual tradition of early Christianity” (Briggman and Scully, Historical Theology: Aims and Methodology, 2).

If you are one of these aforementioned uninitiate, you are not alone—my primary student demographic is South Carolina Baptists who are largely unaware of most of Church History, particularly from the premodern era, with only a few history classes under their belt by the time they enter my classroom.

Course Structure

So how do I go about teaching historical theology, especially to those who do not have much background knowledge? Importantly, my primary aim is to develop in them the skills of historical theology rather than its content. Now, don’t get me wrong—we do learn about important ideas being discussed in the late fourth century, but the course is not a survey or a ‘great ideas’ course for the history of the church. Rather, it tries to instill both the desire and the ability to come back to historical texts throughout their life, engaging them in robust ways.

The first skill associated with historical theology is simply to learn how to read historical figures well. Many students have never picked up a primary source before, even if they have been told about them. Thus, after the initial two weeks of historical context, we only read primary literature. For each day of class, students are required to have read a small portion of a work or two, such as Basil’s On the Holy Spirit and Gregory of Nazianzus’ Epistle 58, mentioned above. During our class period, I typically contextualize the reading for about ten to fifteen minutes, which includes relevant background information—this might be tracing a theological debate or ideas, societal norms, even the specifics of canon law which bear importance for the reading. After this, I walk through the text with the students in a seminar style format, asking students to exegete a passage, chart out an argument, even asking what their favorite insult in the text is (for real, people, the Cappadocians can be impressively catty). In this portion, I want to teach the students how to approach the text—to ask certain types of questions, to inquire in particular directions. These questions must be honest and earnest though, which allows space for ambiguity when the text is ambiguous, even pointing out when a specific argument from one of these fathers is simply not effective. By engaging in this type of discussion together, my students learn how to read historical texts well by have someone to guide them through.

On assessment, I do have a research paper associated with the class, but their weekly reading assignments are unique. Each week, students submit two types of assignments. The first is a creative one that is meant to develop historical thinking in tandem with theological reasoning. In the week on the nature of God, for instance, my students read polemical texts against Eunomius of Cyzicus. Their creative assignment asks them to make a propaganda poster, which details aspects of this debate. And yes, I did receive a ‘mean girls’ poster with the Cappadocian’s faces placed on top of the main characters from the film. Further, they are to write a response to the readings and poster, which details the how they connected the weekly readings to their creative decisions. Thus, they are able to articulate the different approaches to theological epistemology between Eunomius and Gregory of Nyssa, for instance, while still considering the rhetorical, political, and polemical aspects of the debate by creating a propaganda poster. Or, to use another example which gleans different insights, students create a fake dating profile for the ‘ideal’ human being according to a Cappadocian, after reading sermon literature on what it means to be made in the image of God. This forces the students to reflect on the striking differences in basic notions that might be obscured in a cursory reading—the Cappadocians think differently than we do. In other words, these assignments are not only meant to be engaging and entertaining, but to encourage students to think about aspects of historical theology that might be obscured by reading a text on trinitarian theology.

Challenges and Opportunities

Teaching a class in this way, especially to students who have not engaged with the rich tradition, provides unique challenges and unique opportunities—let me provide a few examples. The two biggest challenges are simply historical illiteracy and the inability to look past their own modern questions. As historical theology is multi-disciplinary in nature (using both historical and theological skills and reasoning), it can be challenging to teach students who have almost no prior knowledge of these topics. But, in many ways, this is what provides such wonderful opportunities. Above all, they do not come into the class with the opinion that we need to defend the Cappadocians or read them into current confessional debates, as they tend to do with more modern or familiar figures. My students are coming in with a blank slate and thus are more comfortable with historical ambiguities. To be honest, the Cappadocians are downright mean to Eunomius (read Basil’s Against Eunomius 1.1-8)—and my students are willing to admit it, since they don’t feel a need to view them as perfect exemplars of faith. The Cappadocians also provide a compelling vision of right worship, which doesn’t map onto many modern evangelical notions—this encourages my students to rethink their understandings of worship rather than force the Cappadocians into a contemporary mold. The goal is not to defend, praise, or duplicate a Cappadocian theology for our modern moment, but to learn from them not only as church fathers but as our brothers in Christ, even 2,000 years removed. Thus, my students point out something important which is sometimes obscured in the church’s desire to defend the legacy of their saints—they are also sinners as well. Yes, we must critique Basil’s unwillingness to call the Holy Spirit God with Gregory of Nazianzus, but we must also seek to understand why he is hesitant in the first place. Teaching historical theology in this way can help us do both.