I am not sure how much people read Mark Twain these days, but one work of his has never really got the attention it deserves, even when he was at his most popular. This is his Following the Equator (1897), which is an endlessly quotable account of the world of high imperialism. Although the book is often very funny, I’ll focus here on a couple of examples that are anything but funny, but which do speak powerfully to our current concerns.

In the early 1890s, Samuel Clemens was in deep financial trouble, and nearing bankruptcy. Seeking material for a profitable new book, he undertook a tour of the global British Empire, then approaching its height. He liked many of the people he met on his venture, but he loathed imperialism in general. On one occasion, it was an encounter with a dog that galvanized him into a rhetorical denunciation. In Australia, he discovered the wild dog known as the dingo, and like many travelers before and since, he really liked the animal, which is Essence of Dog. He found it

a beautiful creature—shapely, graceful, a little wolfish in some of his aspects, but with a most friendly eye and sociable disposition. … He is the most precious dog in the world, for he does not bark. But in an evil hour he got to raiding the sheep-runs to appease his hunger, and that sealed his doom. He is hunted, now, just as if he were a wolf. He has been sentenced to extermination, and the sentence will be carried out. This is all right, and not objectionable. The world was made for man—the white man.

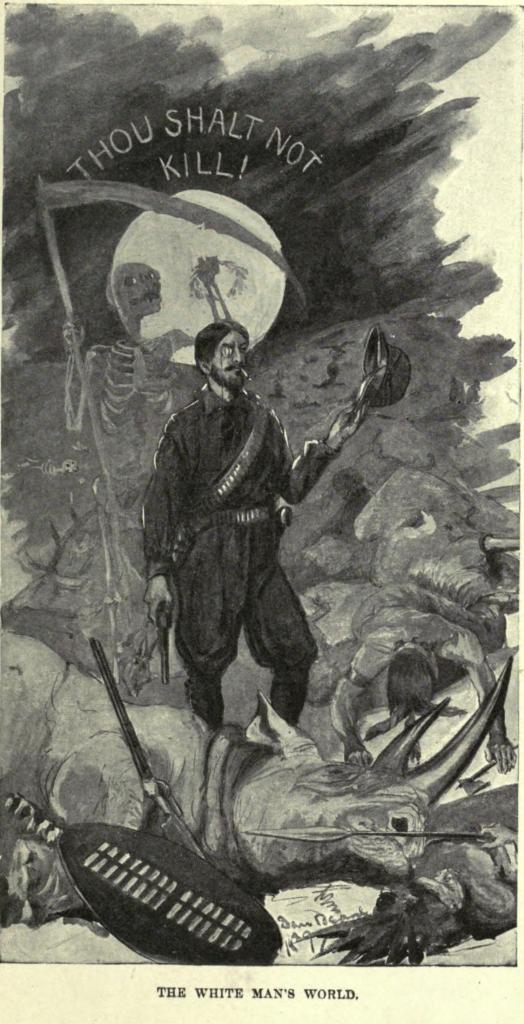

That story was illustrated by a picture which is still amazing in its raw anger, and which actually makes a terrific teaching tool (and a book cover?) It depicts “The White Man’s World,” in which empire-builders randomly slaughter wild animals and Native peoples alike, treating both with equal contempt.

“There are many humorous things in the world; among them the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the other savages.” I may be wrong, but I don’t think at the time many critics of empire so totally linked the devastation of the environment together with violence against Native peoples. The illustrator was Dan Beard who had strong radical connections, as a follower of Henry George. He was also a friend of Ernest Thompson Seton. Together, Seton and Beard laid the foundation for the US Scouting movement, with its commitment to Nature and environmental concerns.

In part, Twain hated imperialism because he associated it very directly with the racial injustice of the America in which he had grown up (he was born in Missouri, in 1835). I will quote here a passage that brings this out so well, and which gives such a notable picture of the racial privilege and violence against which he was rebelling throughout his life. The incident he observes in the 1890s takes place in a hotel in Bombay:

Our rooms were high up, on the front. A white man—he was a burly German—went up with us, and brought three natives along to see to arranging things. …

There was a vast glazed door which opened upon the balcony. It needed closing, or cleaning, or something, and a native got down on his knees and went to work at it. He seemed to be doing it well enough, but perhaps he wasn’t, for the burly German put on a look that betrayed dissatisfaction, then without explaining what was wrong, gave the native a brisk cuff on the jaw and then told him where the defect was. It seemed such a shame to do that before us all. The native took it with meekness, saying nothing, and not showing in his face or manner any resentment. I had not seen the like of this for fifty years. It carried me back to my boyhood, and flashed upon me the forgotten fact that this was the usual way of explaining one’s desires to a slave. I was able to remember that the method seemed right and natural to me in those days, I being born to it and unaware that elsewhere there were other methods; but I was also able to remember that those unresented cuffings made me sorry for the victim and ashamed for the punisher.

My father was a refined and kindly gentleman, very grave, rather austere, of rigid probity, a sternly just and upright man, albeit he attended no church and never spoke of religious matters, and had no part nor lot in the pious joys of his Presbyterian family, nor ever seemed to suffer from this deprivation. He laid his hand upon me in punishment only twice in his life, and then not heavily; once for telling him a lie—which surprised me, and showed me how unsuspicious he was, for that was not my maiden effort. He punished me those two times only, and never any other member of the family at all; yet every now and then he cuffed our harmless slave boy, Lewis, for trifling little blunders and awkwardnesses. My father had passed his life among the slaves from his cradle up, and his cuffings proceeded from the custom of the time, not from his nature. When I was ten years old I saw a man fling a lump of iron-ore at a slaveman in anger, for merely doing something awkwardly—as if that were a crime. It bounded from the man’s skull, and the man fell and never spoke again. He was dead in an hour. I knew the man had a right to kill his slave if he wanted to, and yet it seemed a pitiful thing and somehow wrong, though why wrong I was not deep enough to explain if I had been asked to do it. Nobody in the village approved of that murder, but of course no one said much about it.

It is curious—the space-annihilating power of thought. For just one second, all that goes to make the me in me was in a Missourian village, on the other side of the globe, vividly seeing again these forgotten pictures of fifty years ago, and wholly unconscious of all things but just those; and in the next second I was back in Bombay, and that kneeling native’s smitten cheek was not done tingling yet! Back to boyhood—fifty years; back to age again, another fifty; and a flight equal to the circumference of the globe-all in two seconds by the watch!

I am not saying that this is the most eloquent or damning account of the brutality associated with American slavery, but for the casual and everyday violence of the system, which so thoroughly affected ordinarily decent people like Twain’s father, this is revealing.

I’ll have more to say about Following the Equator.

On Twain in politics, see Stephen Kinzer, The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire (Macmillan 2017).

Susan K. Harris, Mark Twain, The World, And Me: Following The Equator, Then And Now (University of Alabama Press, 2020)