I once spent several years on a teaching team with the same group of people. One of them, a man I'll call Tom, exuded a loving, supportive presence, expressed not so much in words, but in the affectionate aura that he brought into a room. Another, whom I'll call Don, exuded a kind of judgmental harshness. I trembled when I had to present ideas to him, because most of the time he shot them down. We loved Tom and often resented Don, yet we all knew that they were both essential to our group. In fact, when Don tired of the unpopular role of critic, and started holding back his opinions, we all begged him to get real, and be his acerbic self. His challenges kept us at our edge. Tom was a "nice" person, and Don was not, at least not around us. Yet both of them, by being themselves, allowed the whole group to flower.

Part of the reason that expressing your svadharma—being Zusia, or Tom, or Don—is so tricky, is because it is not just a matter of figuring out a set of "right" behaviors and sticking to them through thick and thin. Our dharma in some situations may demand that we follow conventional rules and moral precepts, but at other times we're called to that post-conventional form of dharma that St. Augustine summed up in his famous dictum, "Love, and do as you will." Dharma is alive, and it changes, day by day, year by year, and situation by situation.

Judy, a social activist married to a fellow aid worker and living in Zambia, had no doubt about her life work until she got pregnant and began to wonder if she wanted to raise her child in the bush. Darren is offered a grant that will free him to finish his novel, then finds out that the grant's corporate sponsor is a well-known corporate polluter. Larry has a weekend meeting with a prospective client, but his daughter is failing geometry and has asked him to stay home and help her. These are the kind of large and small decisions that dharma is all about. What personal compass should Judy and Darren and Larry use to make their decisions? Should they follow their feelings, which may or may not be skewed by hidden desires or emotional wounds or cultural prejudices? Apply personal principles? Look for the higher law in the situation? Go with their intuitive "hit"? Is doing the right thing about the greatest good for the greatest number (in which case, as one great thinker said, we should be thinking about what is good for viruses!)? These are all fundamental questions of dharma. And they can be really hard to answer.

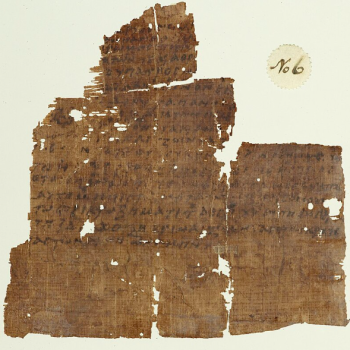

The guidelines I've found most helpful in resolving these questions come from a traditional text of the Upanishadic tradition of India, the Yajnavalkya Samhita. Of course, like most ancient wisdom, the text needs to be periodically re-interpreted to suit contemporary conditions, and so I offer it to you with a few adaptations of my own, and a suggestion that you experiment with it yourself.

The text offers four clues to correct dharma, and one overall "rule" that trumps them all. Here are the four: 1)"The Vedic scriptures and other sacred texts, 2) the practices of the good, 3) whatever is agreeable to one's own self, and 4) the desire which has arisen out of wholesome resolve—all these are known to be the sources of dharma." Then the passage goes on to tell us the real bottom line: "Over and above such acts (as) . . . self control, non-violence, charity, and study of truth, this is the highest dharma: the realization of the Self by means of yoga."

Here's how I suggest you work with these prescriptions. For "Vedic scriptures," you might substitute the wisdom of a tradition you trust—the yamas and niyamas of the yogasutra, the Sermon on the Mount, or a universal teaching like: "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." My Guru used to say that we know we've imbibed spiritual wisdom when it arises spontaneously in moments of intense stress: "When you're angry, the teaching of non-violence should arise," he used to say. "When we're tempted to take something that doesn't belong to us, the teaching of non-stealing should come before our mind."

The second yardstick for right action, "the practices of the good," invites us to channel the discernment we've received, often unconsciously, from observing the people we admire. When I'm trying to make a choice that demands diplomacy and discriminating wisdom, I often ask what my brother David would do. When the question is "What's the most loving choice?" I think of my friend Lee. And when I need to practice equality awareness, or when faced the choice between the demands of society and the demands of my soul, I take inspiration from my teacher's ability to see everyone as equal, and to choose truth over comfort. Even more powerful is to turn to the sage inside. Often, one of my favorite forms of self-inquiry in moments of indecision is to ask myself, "If you did know the right thing to do, what would it be?"