Possibly the most well-known tragedy from antiquity is Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannos, or “Oedipus the King”. The tale is disturbing: Oedipus was that “most wretched of all men” who had been fated unknowingly to kill his father then marry his mother in fulfillment of an oracle delivered about him before his birth. Raised by parents who were not his own, he came to Thebes after killing a man on the path down from Delphi (in an act of ancient road rage), solved the riddle posed by a sphinx who had been plaguing the Thebans, and received the hand of the queen as his reward. Sophocles’ play is a masterful piece of whodunit detective work. The plot follows Oedipus, now the father of several children by the queen whom no one yet knows to be his mother, in his attempt to discover the killer of the former king. Climactic points arise in the twin recognitions that the man he murdered years before was the king, his father, and that the woman he married is his mother. The tragedy is especially rich with dramatic irony, since Oedipus’ reputation has long preceded him and we, the audience or readers, already know that he is the unwitting culprit of the crime for which he is the chief investigator. But aside from the natural draw of reading an ancient, dramatized version of ironic detective fiction, why has the Oedipus Tyrannos garnered so much attention in places, times, and cultures far distant from its original performance in the Dionysiac festival at Athens in roughly 429BC?

The tragedy is still being read today in high schools and colleges, whether public or private. And, although its usefulness may have long become opaque to students and teachers alike, it is not merely a rusted part of the old, sputtering curricular machine of the public school system. The Oedipus Tyrannos has had a remarkable staying power. In fact, in spite of only garnering second place at the festival, Aristotle later considered it the quintessential tragedy. Writing nearly a hundred years after Sophocles’ tragedy, he thought the issue hinged upon the relatability of Oedipus to those who watched or read the tragedy. In his Poetics, Aristotle argued that what made a good tragedy good was that its tragic hero was a person like us, not a god or a villain, purely good or insidiously evil.

In Aristotle’s view, a tragedy’s protagonist should be possessed of a hamartia. He never explained what exactly he meant by this otherwise relatively common word and scholars still debate as to whether its meaning points more to a fundamental “flaw” of the person’s character or is just a tragic “mistake” they have inadvertently fallen into. But, aside from this flaw or mistake, the tragic hero must be a relatively decent person – just like us (or just like we want to see ourselves), not paragons of perfection but not downright evil either. If we can relate to them sufficiently, their jarring reversal of fortune will provoke in us the tragic emotions of pity and fear: pity for their sad misfortune and fear that what happened to them could happen to us. It is not our fear of them. It is rather a fear that we are enough like them that their fate could become ours.

I wonder if Oedipus’ hamartia, is not a mere mistake that can be blamed on the divine realm or on our subconscious desires (as Freud famously thought in his notion of the “Oedipal complex”) but is in fact a flaw of his character. Many have suggested with a good deal of plausibility that he does exhibit a high degree of arrogance or hybris. Indeed, his unquestioned assumption while looking for the murderer is that of his own innocence and righteousness. It is this faulty assumption that leads him erratically to cast accusations of guilt upon others. The issue of his arrogance is a deep one. It is grounded in the text of Sophocles’ play: the Chorus at one point ominously cries out that “Hybris begets the tyrant (the tyrannos)” (line 873). At the same time, the issue is more far-reaching than we might at first realize.

In fact, there are two points that are recalled by the tragedy, only one of which is given explicit consideration in Sophocles’ text, and I believe that together they might be key to interpreting the play and the person more fruitfully – especially for Christian readers. First, if we look years before the opening of the play, Oedipus had solved the riddle of the sphinx, which in its more popular form ran: What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening? No one had been able to solve the riddle until Oedipus saw through it: a human being (who crawls on all fours in the “morning” of life, walks on two legs in their prime, and then walks with the help of a cane in the “evening” of life). The sphinx was forced to withdraw from the land and in the several years preceding the play Oedipus was seen as a savior and “wise above all other men to read life’s riddles” (lines 33-34; transl. Kitto).

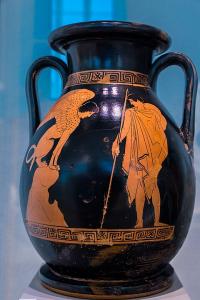

Secondly, however, there was at the same time something Oedipus did not know – even beyond the identities of the man he had killed and the woman he had married – and it was about himself. He walked with a limp. Scars of an unknown trauma from his infancy marked both of his ankles. Most ironically, his name is what we can call a nomen-omen, a name that bears some meaning for his identity or future destiny. The name Oedipus, spelled in Greek Oidipous, is in fact a compound name of two possible combinations of words: it means either “swollen foot” (oidos + pous) or “I know my foot” (oida + pous). Now, Oedipus certainly had swollen, damaged feet; some ancient art depicts him with swollen feet and holding a cane. At a critical point in the tragedy, the old herdsman who had taken the infant Oedipus years before is brought on stage and directly raises the painful issue of his feet (at lines 1034-1036; transl. Kitto).

Herdsman: Your ankles were pinned together. I set you free.

Oedipus: That dreadful mark – I’ve had it from the cradle.

Herdsman: And you got your name from that misfortune too, the name’s still with you.

Oedipus acknowledges the scars, but did he know his feet? Did he know what had made them scarred and misshapen? Some have taken this deeper and wondered whether his feet could stand metaphorically for his origins, the basis on which his life stood. In fact, Oedipus knows neither his feet nor his origins nor the ways in which both were interconnected. He could scarcely have imagined that his true parents were the king and queen of Thebes, that they had attempted to avoid the fulfillment of the horrific oracle about their son and so had sought to expose him as an infant in the wilderness (a practice widespread in antiquity); and that they had a spike driven through his ankles so that he could not crawl off but would die the more quickly when abandoned.

As the play progresses and Oedipus incrementally realizes with horror who he is, we are able to watch in excruciating detail his realization that any true knowledge of himself could not be assumed on the fact that he was wise “to read life’s riddles” or that he knew how to pursue the investigation of the king’s murderer thoroughly and effectively. His superior knowledge lay in the area of theory: the answer to the riddle was a generic human being – no one in particular, just any human. But his self-knowledge, the knowledge of who he was in particular, was a warped tissue of unresolved questions and failure to reflect on the mysteries of his own life and experiences. More than anyone in Greek myth, he exemplifies the truth of the prophet: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?” (Jeremiah 17:9, KJV). The words of the prophet reveal that Oedipus’ failure to read himself truthfully is a failure endemic to all of us. Oedipus’ failure is our own.

In another riveting investigative narrative of antiquity, Augustine becomes aware of this unsettlingly universal sort of Oedipal complex, this impulse towards self-deception that is ingrained in all humans: “But You, O Lord… turned me towards myself, taking me from behind my back, where I had placed myself while unwilling to exercise self-scrutiny; and you set me face to face with myself…, and thrust me before my own eyes, that I might discover my iniquity, and hate it. I had known it, but acted as though I knew it not — winked at it, and forgot it” (Confessions 8.vii.16; transl. Pilkington).

Oedipus is not merely a man fated to perform heinous deeds at the whim of forces beyond his control. He is an embodiment of the universally human temptation to distract ourselves with our successes, avoid facing who we really are, cast blame on others while refusing to suspect our own selves, and perpetuate lives that are a tangled skein of self-deception and self-comforting hybris. May God demonstrate his “severe mercy” upon us (to use another Augustinian phrase) and place us in front of ourselves; only then will we reckon fully with the twin facts that we are not the saviors of ourselves or others, and that salvation not condemnation comes from the Divine (Rom. 8:1) as the true oracles have predicted.