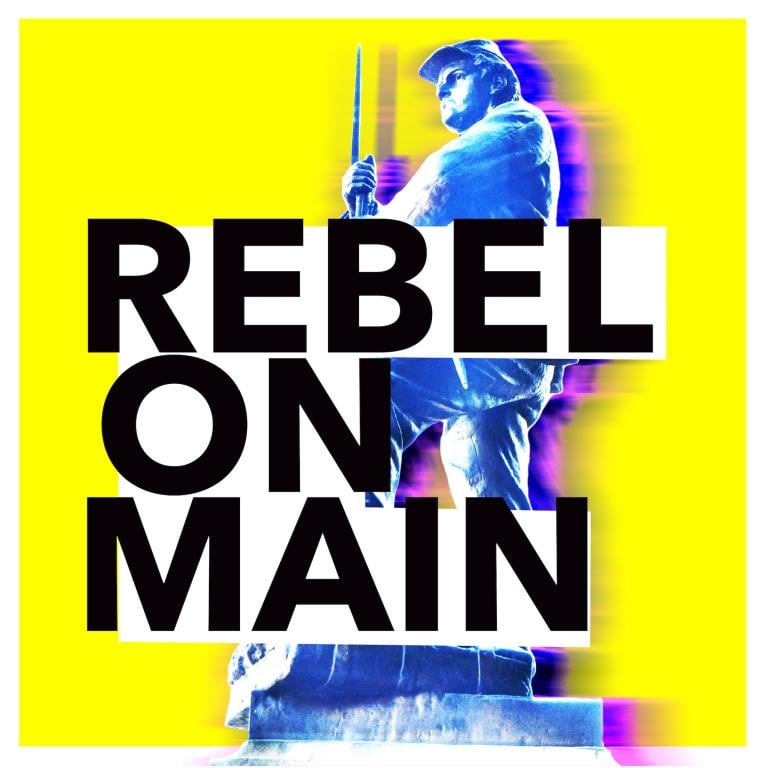

The Confederate on Main Street is imposing. Cast in bronze, he’s seven feet tall. His left foot thrusts forward. Both hands clutch a rifle and bayonet. If provoked, he would be eager for the fray. That’s how the local newspaper described him at his dedication in 1896. Over 125 years later, he still stands atop an eleven-foot granite pedestal on the Jessamine County, Kentucky courthouse lawn. His rebel eyes still stare defiantly at the north.

I encountered him soon after I arrived in Jessamine County to teach at Asbury University. The beautiful bluegrass region of Kentucky was the most southern place I had lived, and this Confederate statue seemed a fascinating regional exoticism. Before long I was taking students in my “War and American Memory” course to the courthouse lawn to analyze his posture, the inscriptions on his base, and the surrounding streetscape.

What we found proved so interesting that I decided to write a microhistory. How has Civil War memory evolved in this single Kentucky county? Why was the statue erected in a state that never left the Union? How did it end up with a Confederate belt buckle and a Union hat? How has its meaning changed through Jim Crow, the Spanish-American War, the civil rights movement, racial retrenchment, and our era of Black Lives Matter and Back the Blue?

I was halfway through drafting this biography of a statue when the protests began. Initially, in the hot weeks of June of 2020, protestors focused on George Floyd and on Breonna Taylor, who had been killed by police in her bed just eighty miles west in Louisville. But protesters soon trained their sights on the Confederate statue looming behind them. I pulled out my Zoom H5 recorder and began four years of journalistic coverage, historical research, and audio production. The result is Rebel on Main, a limited series podcast that launched this week.

I was halfway through drafting this biography of a statue when the protests began. Initially, in the hot weeks of June of 2020, protestors focused on George Floyd and on Breonna Taylor, who had been killed by police in her bed just eighty miles west in Louisville. But protesters soon trained their sights on the Confederate statue looming behind them. I pulled out my Zoom H5 recorder and began four years of journalistic coverage, historical research, and audio production. The result is Rebel on Main, a limited series podcast that launched this week.

My reporting, not surprisingly, revealed deep polarization. Some locals felt a deep attachment to the statue. They resented opponents for wanting to “erase history.” Others despised it. Decrying the statue as a deeply racist artifact of Jim Crow, they wanted it to be destroyed. To me, the intriguing feature of this conflict wasn’t the different opinions. As I stood in the midst of yelling and chanting at Black Lives Matter protests and Back the Blue rallies, I was struck by the depth and intensity of emotion.

The fraught moment got me thinking anew about questions that have long preoccupied historians. Are memorials reflections of the past? Or do they reflect the moment in which they were created? Or both? And what do we do with static memorials when interpretations of the past change?

In the spirit of these questions, I don’t offer a coherent, polished narrative in the podcast. Instead I invite listeners to accompany me in my research. I want them to see how narratives are built. Like the Pompidou Center in Paris, which makes architecturally visible the building’s plumbing, heating and cooling, and electrical systems, I put the guts on the outside.

I begin at the Jessamine County Public Library. Listeners follow along as I click and whir and ratchet my way through the 1880s and 1890s on a microfilm machine. They learn about the bizarre construction of the statue—how it began with a Union identity and was regalvanized to Confederate. They accompany me to the county clerk’s office. There a friend, a former paralegal, teaches me to read slave schedules and marriage records and deed books. We find complicated, contradictory facts: rapes of enslaved women, but also evidence that the Youngs, a prominent Jessamine County family who helped erect the Confederate statue, emancipated a Black man in the 1850s. What does it mean that their son Bennett, a Confederate veteran and prominent attorney, legally defended a Black man in the 1890s but never challenged Jim Crow?

I also wrestle with who gets to tell stories. For years I had heard that members of the Gates family refuse to walk by the Confederate statue. That’s because they intimately knew the story of a lynching from a sycamore tree beside the statue. Their ancestor had watched that lynching amidst a crowd of thousands of onlookers and had passed the memory through the generations. To this day, whenever the Gateses need to do business in the courthouse, they enter through the back—as if Jim Crow never ended.

I meet a Gates grandson in the podcast. Even though we become friends, he doesn’t seem to trust me with his family’s stories. I begin to wonder if my excavation of Black stories is just an academic puzzle that flies above his pain. And even if I mean well—and I think I really, truly do—am I acting like a white savior? Am I telling stories the Black community should be telling for itself? In the end, my new friend grants me an interview, and we discuss these questions of who should tell which stories—and whether I should include this one.

Then I head to the state capital, Frankfort. I visit the Kentucky Historical Society to examine a gruesome artifact that memorialized this Jessamine County lynching. I describe what it’s like to gingerly hold this cold hard object that bears the image of a man hanging from a tree. I describe what it’s like to see its decorative beading and to realize that this genteel spoon is a celebration, not a lament, of the lynching. As a historian—as a human being—I wrestle with my own emotions of revulsion and anger while I contemplate this “lynching spoon.”

Then I head to the state capital, Frankfort. I visit the Kentucky Historical Society to examine a gruesome artifact that memorialized this Jessamine County lynching. I describe what it’s like to gingerly hold this cold hard object that bears the image of a man hanging from a tree. I describe what it’s like to see its decorative beading and to realize that this genteel spoon is a celebration, not a lament, of the lynching. As a historian—as a human being—I wrestle with my own emotions of revulsion and anger while I contemplate this “lynching spoon.”

I also wrestle with source selection. In Episode 6 I describe the efforts of a political activist who spent three hours a night working through a list of 13,500 Democrats to conduct a telephone “survey” about the Confederate statue. It turns out that he was leveraging local affection for the statue to defeat Carolyn Dupont, a fellow historian of religion, author of the highly regarded book Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, and candidate for the Kentucky House of Representatives. When I finally make contact with the activist, I learn that he lives just two doors down from me. He’s my neighbor. Over half a dozen interviews with him, I wrestle, again, with my own emotions. I see unkindness in myself as I get angry with my neighbor for using the Confederate statue as a weapon against my friend. As I write the first draft of the episode, I find myself picking out my neighbor’s most inflammatory lines, not the lines that would demonstrate his thoughtfulness. I discover that I too am tempted to use history for particular ends.

Through all seven episodes of Rebel on Main, I try to show that constructing historical narratives is an exceedingly human process. The “facts” that historians (and builders and removers of memorials) select depend on their own histories, social locations, and anxieties and hopes. The facts depend on which sources happened (or were designed) to survive the sands of time. Just as no narrative is pure history, no memorial reflects the true complexity and contingency of the past. Perhaps these distinctions can free my county to think more deeply about—and perhaps even to reimagine—our courthouse lawn.

***

This essay was first posted at Current.