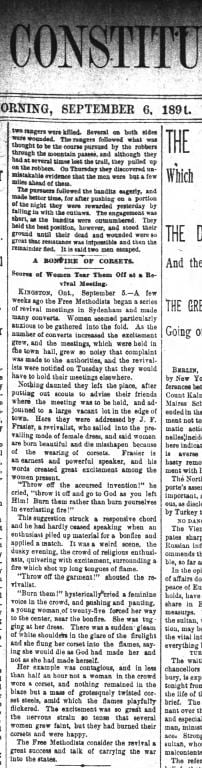

In 1891 a salacious article was printed in many North American newspapers. Entitled “A Bonfire of Corsets,” it chronicled a frenzied overthrow of patriarchy at a Free Methodist revival in Kingston, Ontario.

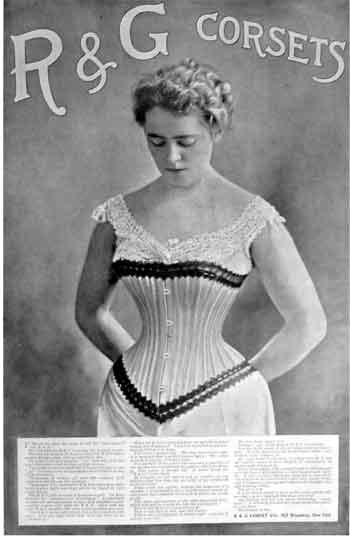

The revival began in Kingston’s town hall. Over the course of several weeks, as the story was told, many anxious women were gathered into the fold. So many, in fact, that the revivalist J. F. Frasier, described as an earnest and powerful speaker, moved the proceedings to a nearby large vacant lot. When the preaching resumed, Frasier uttered a provocative line. “Women are born beautiful,” he said, “and die misshapen because of the wearing of corsets.”

His words created great excitement among the women present. Egged on by the crowd, Frasier continued, “Throw off the accursed invention,” he cried. “Throw it off and go to God as you left him! Burn them rather than burn your souls in everlasting fire!” This suggestion struck a responsive chord, and he had hardly ceased speaking when an enthusiast piled up material for a bonfire and lit a match.

The description of the events that followed is worth quoting in full:

It was a weird scene, the dusky evening, the crowd of religious enthusiasts quivering with excitement surrounding a fire which shot up long tongues of flames. “Throw off the garment,” shouted the revivalist. “Burn them!” cried a feminine voice in the crowd, and pushing and panting a young woman of twenty-five forced her way to the center near the bonfire. She was tugging at her dress. There was a sudden gleam of white shoulders in the glare of the firelight, and she flung her corset into the flames, saying she would die as God had made her and not as she had made herself. Her example was contagious, and in less than half an hour not a woman in the crowd wore a corset, and nothing remained in the blaze but a mass of grotesquely twisted corset steels. The excitement was too great and several women grew faint, but they had burned their corsets and were happy: The Free Methodists consider the revival a great success, and talk of carrying the war into the States.

There is much that could be said here about collective effervescence, about repressed sexuality, about how starved these women must have been for acknowledgement of their experiences (and of oxygen), and about the economies of journalism that caused this article to be reprinted in the Scientific American, the Saturday Evening Mail, the Atlanta Constitution, the Wichita Daily Eagle, the Boston Globe, and dozens of other newspapers.

There is much that could be said here about collective effervescence, about repressed sexuality, about how starved these women must have been for acknowledgement of their experiences (and of oxygen), and about the economies of journalism that caused this article to be reprinted in the Scientific American, the Saturday Evening Mail, the Atlanta Constitution, the Wichita Daily Eagle, the Boston Globe, and dozens of other newspapers.

I simply want to point out how this moment of women’s empowerment reasserts sexual norms in the end. The corset, a tool of patriarchal oppression, is thrown into a fire and destroyed, but it is done so in a way that fulfills male fantasies. Indeed, the highly sexualized images—“dusky evening,” “long tongues of flames,” “tugging at her dress,” “pushing and panting,” “sudden gleam of white shoulders”—must have left readers very open to the idea of “carrying the war [against corsets] into the States.”

Moreover, these women converts are described as unthinking, emotive subjects of male authority. Frasier is getting the credit here. They’re being offered liberation, but only into the fold of organized religious communities dominated by men.

The irony here is that the feminists of the 1960s, reviled and celebrated for burning their bras, never actually burned them. Revivalists of the nineteenth century, reviled and celebrated for propping up patriarchy, actually did burn theirs.