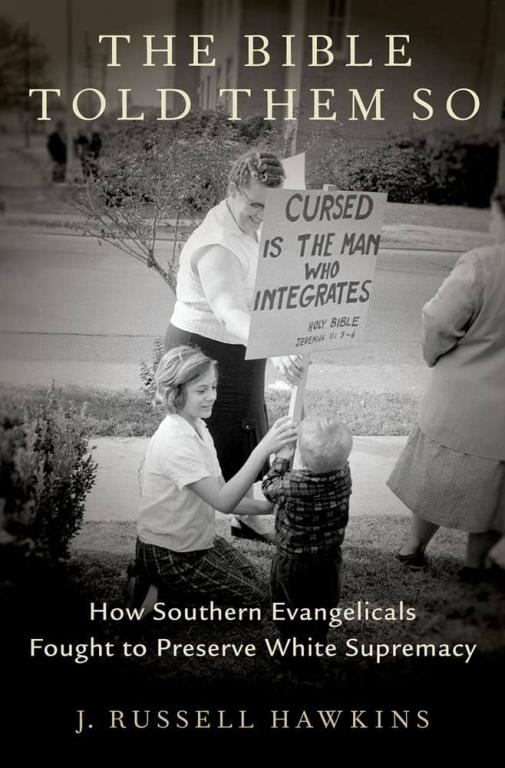

I’m pleased to welcome Rusty Hawkins to the Anxious Bench. He is a professor of humanities and history at Indiana Wesleyan University and dean of the John Wesley Honors College. Hawkins studies race and religion in recent America and is the author of The Bible Told Them So: How Southern Evangelicals Fought to Preserve White Supremacy, which was published by Oxford University Press in 2021. –David

***

David: The last sentences of the introduction read, “Scripture was a significant source of the problem . . . The pages ahead explain why.” What were the key passages and theological principles segregationists used to show that “the Bible told them so”?

Rusty: The two scriptural book-ends for segregationist Christians were the Genesis account of the Tower of Babel and Paul’s preaching in the Athenian marketplace in the book of Acts. Segregationist Christians read into the Babel account God’s original intent for racial separation. Paul’s sermon in Acts 17:26 reiterated this divinely endorsed segregation declaring that God “set the bounds of (humanity’s) habitation, which in the minds of segregationist Christians meant that even in the New Testament, God continued to support segregation. In between Genesis and Acts, segregationist Christians were adept at finding support for segregation in the Levitical code (don’t weave unlike fabrics into a garment) in Jewish prohibition of intermarriage with foreigners, and even in the fact that Jesus said he will “segregate” the sheep from the goats at his final judgement. I try to lay out all of these scriptural proofs as thoroughly and systematically as possible in the book’s second chapter, but readily acknowledge that no reader today is likely to find them persuasive.

David: Historian David Chappell showed that the Bible galvanized civil rights activism. You show the opposite. Has your research changed your view of the Bible? Does it seem like a more unstable text because so many American Christians have used it toward such different ends?

David: Historian David Chappell showed that the Bible galvanized civil rights activism. You show the opposite. Has your research changed your view of the Bible? Does it seem like a more unstable text because so many American Christians have used it toward such different ends?

Rusty: I wouldn’t say my research has changed my view of the Bible, but it has certainly changed my view of how people read and come to interpret what the Bible means. This isn’t a novel insight on my part. The story of Protestantism told one way, for instance, is the story of Christians endlessly splintering over differing interpretations of biblical texts. What struck me most about my research from the civil rights period is how closely tied orthodoxy became to the notion of majority rule. So, for example, it didn’t matter in the minds of segregationist Christians that very few academic theologians or seminary-trained pastors agreed with their interpretations of the Bible endorsing Jim Crow. Rather, they felt their interpretations were correct because the majority of Christians they knew and interacted with agreed with their interpretation. Segregationist Christians were always claiming that their views were in the majority precisely because majority rule was how they determined orthodoxy. But this insight from the civil rights period is just an extension of what Nathan Hatch identified decades ago as the democratic impulse of American Christianity.

David: Strom Thurmond, the famously racist 48-year senator from South Carolina, makes several appearances. How closely tied was he to the churches you studied?

Rusty: Thurmond was first a foremost a politician. He was active in correspondence with Christians in his state who wanted him to fight against civil rights reforms and in letters affirmed he was in agreement with his constituents’ views. But I wouldn’t say he was a chief contributor to segregationist Christianity. However, as a central node for segregationists throughout the South, his papers (especially his correspondence) were invaluable for my ability to reconstruct what segregationist Christians said and believed throughout the civil rights era.

David: You tell many stories of southern pastors who resigned or were fired for their support of racial integration. Do you know what happened to them? Did they turn toward the mainline? Did they pursue other vocations?

Rusty: Of all the stories that appear in the book, I only know what happened to two Methodist ministers were forced out of their pulpits for speaking out against the Citizens Councils (an anti-civil rights organization that used economic intimidation to keep Black southerners for pushing for civil rights reform) in 1955. In both these men’s cases, they were reassigned to administrative positions within the denomination and as far as I could tell, did not serve again as ministers.

David: You stress continuity more than discontinuity in tracing the evolution of segregationist theology to colorblind individualism. How did colorblindness maintain racial segregation?

Rusty: Yes, one of my main arguments is that the explicit segregationist theology of the 1950s and early 1960s in southern evangelicalism begot colorblind individualism by the late 1960s and early 1970s. The major civil rights legislation of the mid 1960s (Civil Rights Act of 1965; Voting Rights Act of 1965), coupled with the growing revulsion of the American public toward segregation due to the media’s widespread dissemination of images showing state violence enacted upon non-violent protestors (police dogs, fire hoses, tear gas, etc.) made segregationist Christians less comfortable talking so openly about God’s desire for segregation by the end of the 1960s. When Christian colleges and denominations came around to actually embrace integration and started advocating that they break down the walls of segregation within their own institutions and become more attentive to race in an effort to promote integration, segregationist Christians found themselves in a tight spot. On one hand, they still believed that racial separation was God’s plan. And yet, saying such things publicly by the late 1960s risked making them appear thoroughly out of step with an American society that in many ways was “bending toward justice” the aftermath of the violent protests in places like Birmingham and Selma. So what these segregationist Christians did was modify their language. They started talking about how churches and Christians were putting too much emphasis on race and that the best way toward a harmonious future would be to just stop talking about race altogether. Rather than taking intentional steps to address structural injustices in their churches, these segregationist Christians advocated for treating individuals by their own merits without accounting for race. What I need to stress, though, was that the people who were making these arguments for colorblind individualism in the late 1960s and early 1970s were the same people who ten years earlier were saying that God was a segregationist. They were not making good-faith arguments about doing what was in the best interest of their fellow Black Christians. They were fashioning a new defense of segregation and calling it colorblindness. By ignoring race, by ignoring intentional policies that would ensure racial diversity in their institutions, these white Christians were supporting the status quo—which, not incidentally was segregated.

David: You found a smoking gun in the archives: a letter in the archives by a man named William Workman that marked a key moment in the transformation of segregationist Christianity. Tell readers what was in that letter.

Rusty: William Workman was a prominent Methodist layman and one of the most influential segregationists in South Carolina. When the Methodist church started the process of undoing the racial segregation that was built into their denomination, Workman was one of the most outspoken critics. Workman was one of the key architects of the colorblind individualist approach to avoiding racial integration in the Methodist church. He helped form a group of conservative Methodists who goal was to block the integration of their denomination and he was the one who floated the idea that one way they could successfully outmaneuver the integrationists was by saying that Christians should be colorblind and stop paying so much attention to race. (Mind you, Workman had been obsessive about race and policing racial boundaries for all his adult life prior to this new tactic of “colorblindness.”) The smoking gun that I discovered in the archives was a letter Workman wrote to his fellow conservative Methodists outlining his colorblind strategy. In the letter (which Workman later sent out for publication to newspapers across the state), Workman defended his colorblind individualist rhetoric with the words penned in 1896 by a Supreme Court Justice named Henry Billings Brown. Justice Brown wrote that states should stop being so attentive to race, and instead should focus on the “natural affinities” and “individual merit” of people when constructing laws and ordinances. Workman liked Brown’s language from the 1896 decision and incorporated it into his strategy. The kicker was that the decision Justice Brown was writing in 1896—and Workman was citing in 70 years later—was the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case, which had made Jim Crow segregation the law of the land. The fact that Workman used the language of Plessing when laying out his case, was a not-so-subtle nod to the fact that segregation was the intent of the first generation of advocates for colorblind individualism.

David: Why have white evangelical efforts at “racial reconciliation” fallen “spectacularly short of their goals”?

Rusty: One of the biggest reasons for this failure is precisely because white evangelicals for so long thoroughly adopted the colorblind approach to issues of race that was championed by folks like William Workman. For instance, I came of age in white evangelicalism in the 1980s and 1990s and was taught (implicitly for the most part, but occasionally, explicitly) that talking about race was wrong and just exacerbated racial tensions that would go away if we just stopped “picking at that scab.” By the time white evangelicals started waking up to the idea that racial division were a problem that needed to be addressed in the late twentieth century, they (we) were thoroughly unprepared to think about how problems could or should be addressed structurally. Instead, white evangelicals thought the best way to “improve” on the issue of race was to simply treat individuals with respect, kindness, and dignity. Don’t mishear me, these are GOOD things, but it doesn’t do much to move the needle on the kind of racialized power inequities and racialized understandings of theological normativity that sociologists still find endemic in American evangelicalism.

Rusty: One of the biggest reasons for this failure is precisely because white evangelicals for so long thoroughly adopted the colorblind approach to issues of race that was championed by folks like William Workman. For instance, I came of age in white evangelicalism in the 1980s and 1990s and was taught (implicitly for the most part, but occasionally, explicitly) that talking about race was wrong and just exacerbated racial tensions that would go away if we just stopped “picking at that scab.” By the time white evangelicals started waking up to the idea that racial division were a problem that needed to be addressed in the late twentieth century, they (we) were thoroughly unprepared to think about how problems could or should be addressed structurally. Instead, white evangelicals thought the best way to “improve” on the issue of race was to simply treat individuals with respect, kindness, and dignity. Don’t mishear me, these are GOOD things, but it doesn’t do much to move the needle on the kind of racialized power inequities and racialized understandings of theological normativity that sociologists still find endemic in American evangelicalism.

David: What are you working on next?

Rusty: I’m working on a religious biography of former Alabama governor George C. Wallace. Wallace is arguably the most famous racist (though he always contended he was a “segregationist,” not a racist) in American history. And yet he supposedly had a born again experience after his attempted assassination in 1972 and over the next 25 years went looking for redemption from his segregationist past. By the end of his life, he’s exchanging Christmas cards with Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell–Franklin Graham even gave his eulogy. So, I’m trying to figure out how Wallace’s religious beliefs (particularly as they related to race and politics) changed over time and how his life might reveal the possibilities and limitations of certain conceptions of “forgiveness” in history.