My childhood experience of Christmas morning, like most, was marked by certain traditions. My siblings and I would wake up and excitedly descend to the living room to see a mass of presents under the tree. Then, we would eat my mother’s delicious monkey bread rapidly to get to the presents as quickly as possible. Before we tore open the wrapping paper concealing those treasures though, my father would pull out his Bible and slowly read from Luke 2 (it felt like an eternity as an 8-year-old!), reminding us why we celebrate Christmas—God became flesh to save us from our sins.

Now, as a parent myself, I find great joy in this same tradition—reading ‘the Christmas story’ before we open our gifts together. Further, I have added advent traditions, including reading Christian writers from the early church during Advent (see my thoughts on reading the early church devotionally, here). This year, I have been reading Ephrem the Syrian, who reflects on this same theme that my Father read from Luke, that the Christ child is our savior: “Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord (Luke 2:11).” Ephrem does something that I rarely see in modern discussions of Christ’s birth though, at least in Christmas sermons, devotionals, and hymns. Ephrem emphasizes the paradox of the incarnation, that “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14), what we might call the Johannine Christmas story. Therein, Ephrem uses striking and provocative language to claim that Christ, in the nativity, is not only child—he is also mother.

Background and Work

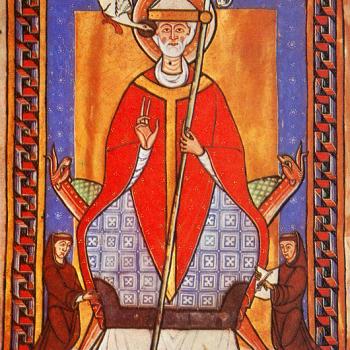

Ephrem is the most famous Syrian writer from the patristic period, venerated by both the eastern and western church. He was born in Nisibis (now Nusaybin, Turkey) in 306, where he spent most of his life as a deacon, though he was forced to Edessa (Şanlıurfa, Turkey) near the end of his life where he taught at an academy. Despite his importance and intellect, he was never ordained or promoted to a higher office—he continually refused such posts to focus on spiritual discipline and writing. He wrote over 1,000 works across various genres, including poems, hymns, polemics, sermons, and commentaries. His works have been used in theology and worship throughout the history of the church by Latin, Greek, and Syriac churches. He died in 373, after caring for victims of the plague.

Ephrem is most famous for his beautiful hymns, of which we have 28 devoted to the themes of the nativity. Throughout, he prioritizes a typological reading of the Old Testament, which he connects to Christ himself. If you are familiar with Patristic exegesis, some of these Old Testament ‘types’ that Ephrem employs will be unsurprising—Christ is the second Adam, the second David, etc.. But Ephrem makes some novel connections as well, as seen in Hymn 13 where Isaac, Samuel, and Samson are viewed as types of Christ. The last of those connections is, perhaps, the most striking: “The Nazarite, Samson, gazed at the type / of your courage. He tore the lion apart, / the likeness of death. You ripped [death] asunder / and made the sweet life emerge / from its bitterness from human beings” (Ephrem, Hymns, trans. Kathleen E. McVey, 13.4). Just as Samson killed the lion in Judges 14 and found sweet honeycomb in its carcass several days later, so Christ rips death asunder so that we might find the sweetness of life. Ephrem utilizes this type of exegesis throughout his nativity hymns, especially connecting Christ’s experience to Mary’s.

All Creation Dwells in Christ’s Womb

Ephrem centers Mary in God’s plan of salvation from the very beginning: “Therefore they answered, ‘Today let Eve / rejoice in Sheol, for behold the Son of her daughter (Mary) / as the Medicine of Life came down to save / the mother of His mother—the blessed Babe / Who will crush the head of the serpent that wounded her’” (Hymn 13.2). Mary’s place in salvation history and her unique relationship with Christ is an important theme for Ephrem (for some edifying medieval reflections on Mary and Christ, see Lynneth Miller Renberg’s recent post), particularly as Mary’s pregnancy and birth is the location of a paradox that he wants to draw out: The omnipotent creator God is now a powerless creature, a baby.

Ephrem elaborates on this theme in Hymn 4: “Mary bore a mute Babe / though in Him were hidden all our tongues. / Joseph carried Him, yet hidden in Him was / a silent nature older than everything. / The lofty One became like a little child, yet hidden in Him was / a treasure of Wisdom that suffices for all” (Hymn 4.146-148). The Christ child was like every other baby—unable to speak, young, and simple. But, as Ephrem points out, he is also unique, the eternal Word of God who is wisdom itself.

Ephrem continues with particularly striking language about Christ’s enigmatic nature as eternal creator and newborn baby, focusing on his relationship with Mary.

He was lofty but he sucked Mary’s milk,

and from His blessings all creation sucks.

He is the Living Breast of living breath;

by His life the dead are suckled, and they revived.

Without the breath of air no one can live;

without the power of the Son no one can rise.

Upon the living breath of the one who vivifies all

depend the living beings above and below.

As indeed He sucked Mary’s milk,

He has given suck—life to the universe.

As again He dwelt in His mother’s womb,

in His womb dwells all creation. (Hymn 4.148-154)

The paradox of Christ’s infancy is his very dependence on his mother for life, seen here in the language of dwelling in her womb and breastfeeding. As a human baby, Jesus would have died without Mary’s nurturing—she gives him life. As God though, he also gives life to Mary. Thus, Ephrem provocatively claims that Christ is the ‘Living Breast’ from which life is given, that creation dwells in his womb. Later, he narrows in on Mary herself: “She gave Him milk from what He made exist. / She gave Him food from what He had created. / He gave milk to Mary as God. / In turn, He was given suck by her as human” (Hymn 4.184-185). What a marvel, that the creator is being sustained by his creation while continuing to provide for it!

Christ as Mother and Child

In using maternal language for Christ, Ephrem is not trying to argue that Jesus is literally a mother, as this misunderstands Christ’s divine nature. He is reflecting on the creative work of the Son of God in connection with the creative work of Mary in bearing Christ. As Mary gives Jesus life, so he gives her life. In a later hymn from the perspective of Mary, Ephrem emphasizes the unique relationship she has with this child: she is mother to Christ, but also sister, bride, and daughter:

“Son of the Most High Who came and dwelt in me,

[in] another birth, he bore me also

[in] a second birth. I put on the glory of Him

Who put on the body, the garment of his mother. (Hymn 16.9-11)

Christ carries us, as a woman carries a child—he gives birth to us in baptism and sustains us as a breastfeeding mother. This child is also, in a spiritual sense, a mother.

Ephrem is meditating on the Christmas story, not only through Matthew and Luke, but from John 1 as well—the Word is God, all was created through him, and he came to dwell with us. This paradox, that the creator God became a created child, is a profound mystery that demands reverence and worship. As we meditate on coming of Christ, might we remember that his salvific work is always in conjunction with his creative work. This babe wrapped in swaddling clothes is the one who gives us life.