I am writing this post on December 12, the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a day of great rejoicing in Mexico and indeed throughout the Americas, celebrating that the Mother of God came down in the form of a Nahua to help her Nahua children. I am closer to the story this year than in years past because I am deep into the final chapters of my manuscript about Juan Diego, the 16th century indigenous visionary to whom Guadalupe appeared, which is tentatively scheduled to appear in Ignatius Press’s popular Vision series in Fall 2025. (For a brief overview of this apparition, please see my post, Juan Diego and the Indigenous Engineers of Mexico-Tenochtitlan).

I’ve written about this topic many times, including September 16 – ‘El Grito,’ the Mexican Inquisition, and Our Lady of Guadalupe, Will the real Juan Diego please stand up? Europeanizing an indigenous saint, Did God Prepare Native Peoples in the Americas for Christ? Part I, and Did God Prepare Native Peoples for Christ? Part II.

For this post, I’d like to share selections of my manuscript, reflecting upon the experience of writing a book introducing readers to the beauties of Nahua culture and the Nahuatl (Aztec) language against the backdrop of 1530s Mexico City. Given Ignatius Press’s global reach, this book will do more to challenge stereotypes of savage, heart-sacrificing peoples than all my scholarly publications and plenary speeches about indigenous Christianity.

Anyone familiar with the story knows that few details have come down to us, and even those are disputed; several scholars deny Juan Diego’s existence, among them Stafford Poole, who wrote the definitive scholarly book about it. Plus, the Lady specifically asks Juan Diego not to speak to anyone but the bishop about her appearance. How does one write a captivating story for children with a handful of facts and a handful of characters?

I originally had Juan Diego thinking. A lot. Remembering the past. In his mind. As he walked.

That did not work well. My children, who are my test audience and who generally love my stories, quickly felt lost. After borrowing their books and having long talks about their favorite stories, we co-authored and illustrated a series of little books about a family of flying squirrels who lived in the marsh outside our home, an exercise putting me in the mindset of a child and giving me an idea.

I reworked my manuscript, having Juan Diego interact with animals. More than underscore the close relationship between humans and animals in Nahua culture, it also reflects the practice of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Anthony of Padua, Franciscans like those who instructed Juan Diego. This selection hints about something unusual about this day, December 9, 1531:

“Glancing ahead, the Nahua traveler noticed ambling movement in the shadows close to the earth. Beady eyes and a pointy nose. Tall ears, sharp claws, a thick tail, and an earth-toned, banded shell. ‘Brother armadillo!’ he called out in surprise, for the ayotochtli preferred to hunt under the sun’s warmth. What would prompt him to venture out against his natural instinct? Juan Diego had never seen one out on a December morning, and wondered at the oddness of its presence. ‘It is a bit cold, a bit chilly for your body, is it not?’ he asked softly. The creature paused as it approached the path and turned in the Nahua’s direction, its nose twitching” (manuscript Chapter One).

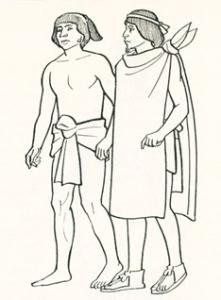

Accurate representation is important, so I write Juan Diego as indigenous as he would have been, having lived most of his life prior to European invasion. He walks barefoot, squats rather than sits when at rest, and wears the simple clothing of a commoner:

“Even though the air was thick with frost, the man was barely clothed. This morning, as he did every morning, he had knotted a simple cloak, or tilmatli, over his right shoulder. Woven from maguey cactus fibers, the undyed cape clung to his shoulders, then fell loosely about him, leaving the right side of his body exposed. Beneath his tilmatli, the man had knotted tightly about his waist a plain cactus-fiber loincloth, called a maxtlatl. His feet, which met the earth firmly, were bare (manuscript Chapter One).

Mesoamerican maxtlatl (loincloth), tilmatli (cloak), cactli (footwear), and traditional men’s hair

I endeavor to find interesting ways to prompt children to think from an indigenous perspective, that is, about Europeans Christians as foreigners, as indeed they were in the Americas:

“… Juan Diego’s soft, chocolate-brown eyes scanned the hillsides as he walked. Like his eyes, his skin was brown, his hair dark and glossy despite his age, and his chin bare. He could not grow a full beard, nor would his hair ever lose its rich darkness. He, along with other peoples in the Americas, had been surprised to learn that hair grew thick along the bodies of foreign men. More surprising still was that European hair, rather than remaining full and bright, thinned and dulled to gray, silver, or even white. The hair of some foreign men completely fell out, leaving a rounded mound of skin rising above their eyes and ears. Juan Diego had never seen such strangeness until he met the Christians” (manuscript Chapter One).

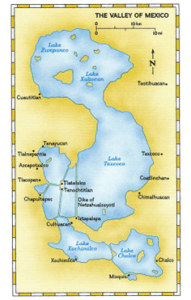

Importantly, what has been termed the “Spanish Conquest” was more accurately a clash between two imperialisms. I call it the Mexica-Castilian War or use the Nahuatl label, the War to End all Wars because guess what? This region was rife with warfare:

“For tens of thousands of years, native peoples like his own had inhabited the Americas, clustering together in villages and city-states they called water-hills, and developing their own languages, cultures, and traditions. Juan Diego’s village, like all those that had been conquered by the Mexica – a powerful people who lived on an island in the nearby capital of Mexico-Tenochtitlan – had adopted Nahuatl, the beautiful, lyrical language of their conquerors, as their own. Warfare and conquest had become so common in these lands, that these Nahuatl-speakers, known as Nahuas, were accustomed to invasion and attack. The Christians might have sailed in from another land, but they were just another group of conquerors in a history filled with conquest” (manuscript Chapter One).

My goal is to teach children without them knowing they’re learning, like this flashback about married life:

“Juan Diego had been squatting as he arranged reeds to dry in the sun so that his wife might weave them into mats to sell in the marketplace. Like most Nahua couples, they were partners. He collected and dried reeds and worked in the fields to grow crops, a portion of which he gave several times a year as tribute to the Mexica, and later, to the Castilians. María Lucía would sweep their home each morning – a Nahua tradition that reverenced the gods by removing tlazolli or filth – crush the maize to prepare tortillas, and provide their meals. On days her husband worked long hours in the fields, she would take him food, then remain to work beside him. She wove all their clothes out of maguey cactus fibers, toasting, dressing, scraping, washing, and treating them with maize water to make them waterproof. She also sold their reed mats in the marketplace, the tianquiztli, because before the Europeans arrived, women served as vendors, buyers, and overseers in the marketplace. After the Castilians took control in 1521, men began entering the marketplace, men like Juan Diego” (manuscript Chapter Two).

Juan Diego’s relationship with his wife has not ended because she has died. Through flashbacks and conversations Juan Diego has with her in “the Land of Heaven, in the Land of Flowers,” she is very much a character in my story.

One of my favorite parts of writing this story has been re-creating the Valley of Mexico in the 1530s, particularly the sensory details of Juan Diego’s walk across the causeway to the island:

“To the right of the causeway lay the shallow, motionless, and murky waters of the lagoon. Once spring-fed from the western mountains, sweet, and full, the lagoon’s cloudy, avocado-colored water now stained the side of the causeway, muddying the shoreline. On the left, the shiny, shimmery waters of Lake Tetzcoco, a low-lying inland saltwater lake, stretched out towards the faraway mountains. Squinting against the sun’s reflection on the water, Juan Diego detected the outline of two towering volcanos beyond the distant shore: the snow-capped Iztaccihuatl, the White-Lady, and her legendary protector, the Popocatepetl, or Smoking-Mountain” (manuscript Chapter Two).

Digital reconstruction of Tenochtitlan and its causeways, aqueducts, and dikes; the curvy dike of Nezhualcoyotl (separating brackish waters from freshwater) is visible on the far right. Juan Diego would have walked toward the island from the causeway on the top right (www.mexicolore.co.uk, Copyright Tomás Filsinger)

There is so much more to share — and perhaps I’ll do so in a future post — but for now, I will stop here.

One of the joys of this book is that I can write the Virgin of Guadalupe as I have always envisioned her: warm, maternal, affectionate, and with a hint of laughter in her chocolate brown eyes. Once the book is published, children around the world will see her this way, too.

More importantly, they will see Juan Diego as the Nahua Christian that he was.