Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy: Did an Ancient Indigenous Tradition Prepare the Americas for Millions of Conversions to Christianity? Part II

This (long) post serves as part two of my response to Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy: How God Prepared the Americas for Conversion Before the Lady Appeared. Part I provides an outline of the book’s argument, which I will not discuss here.

Reading Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy: How God Prepared the Americas for Conversion Before the Lady Appeared at the park while my children were in PE

I thoroughly enjoyed immersing myself in Juan Diego’s world via the Mesoamerican philosophy, anthropology, art, and flower-songs (poetry) in this book. Its content neatly aligns with themes in my APU course: “Native People Before and After Iberian Invasion,” especially because students read sample chapters of my Juan Diego book this week.

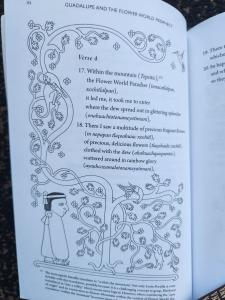

Ultimately, Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy is impressive for what it is – a book written by Catholic authors (who are not trained scholars) for a Catholic press formulating a new argument about the spread of a Catholic devotion. Challenging its classification as a devotional text, the book incorporates a range of interdisciplinary scholarship including anthropology, philosophy, theology, literary criticism, and history penned by European AND indigenous authors. The book’s dedication to locating its discussion within a native context is a departure from similar devotional approaches to Guadalupe, and thus laudable. The indigenous-inspired line drawings that pepper the text further reflect the desire to immerse readers in Nahua culture, and the authors’ translation of some Nahuatl material is noteworthy. Despite my own study of Nahuatl my mastery of this complex tongue remains elementary, so for reference I pulled out James Lockhart’s Nahuatl as Written and consulted the online Nahuatl Dictionary.

Indigenous-inspired images accompanying the English translation of the Cuicapeuhcayotl

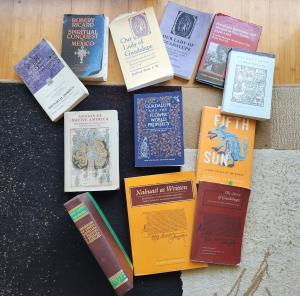

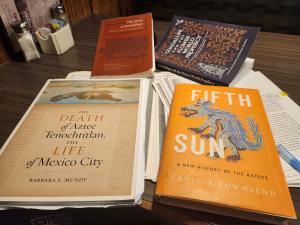

Reading this book did not consist of the simple act of turning its pages. Inspired, I would set the book aside, pull a text off my shelf, and lose myself in it. I didn’t get past the first page’s opening quote from fray Toribio de Benevente Motolinia’s 1541 Historia de los indios de la Nueva España without pulling out my own copy, purchased in Mexico City some 20 years ago. One night I reread Steven Turley’s Franciscan Spirituality and Mission in New Spain, 1524-1599: Conflict Beneath the Sycamore Tree (Luke 19:1-10), and turned frequently to Camilla Townsend’s Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. During discussion of the Guadalupe narrative I had The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega’s Huei tlamahuiçoltica of 1649, translated by Lisa Sousa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart, open beside me. I also pulled out my heavily annotated copy of Stafford Poole’s Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531-1797, which I read in my first History Graduate Seminar at Penn State with Matthew Restall, and my equally worn copy of Robert Ricard’s 1933 seminal work, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, which I read during that same Seminar. Last to come off the shelf was Miguel León Portilla’s 1956 Aztec Thought and Culture. Surrounded by old friends, I felt transported back to my graduate school days.

My current read surrounded by old friends

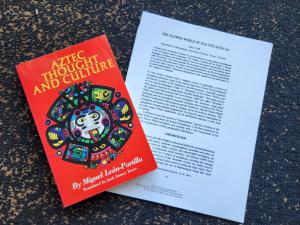

References to the foundational work of Mexican historian Miguel León-Portilla proliferated Flower World Prophecy, but not until I leafed through Aztec Thought and Culture did I realize how much the book’s arguments hinge upon his scholarship. In essence, Flower World Prophecy merges León-Portilla’s understanding of Nahua philosophy as a search for “the only truth” (Aztec, 96) with more recent scholarship among linguists, anthropologists, and art historians demonstrating a Pan-Mesoamerican belief in the Flower World to argue that “for close to three thousand years, the people of Pan-Mesoamerica were supernaturally pointed in one direction, and that was their Christian conversion through the fulfillment of the Guadalupe Event of 1531” (20).

Miguel León Portilla’s 1956 Aztec Thought and Culture and Jane Hill’s “The Flower World of Old Uto-Aztecan” which introduced the pan-Mesoamerican Flower World concept

This realization gave me pause, as our understanding of Nahua culture, language, and philosophy has advanced significantly in the nearly 70 years since León-Portilla published in the 1950s, not least because of the rich archival record uncovered by generations of scholars, many trained in native languages. Contemporary scholars like Camilla Townsend recognize that “it is … difficult to grasp spiritual concepts in the Nahua world due to the limited nature of the evidence. Many have made assertions, but recent work indicates how dangerous such guesswork often has been” (Fifth Sun, 242, fn 50). The sources we have, are, by and large, colonial. This, then, is why the book gave me pause, compelling me to stop and cross-reference its claims. The scholarship anchoring the text is outdated.

Let me set that aside for now. The authors, noting how J.R.R. Tolkien used the language of mythology to share his faith with C.S. Lewis, ask their readers to imitate Lewis, set aside our biases, and approach the Guadalupe Event as “true myth.” Taken as “true myth,” the book’s argument holds and is, in fact, rather compelling, for the authors trace the continuity of two Nahuatl phrases – in xochitlalpan in tonacatlalpan (Flower World Paradise) and in Tloque in Nahuaque (the God of Far and Near) from ancient Nahuatl flower-songs to indigenous paintings decorating colonial Catholic churches. Viewed through a critical historical lens, however, the book’s claims falter.

The core argument rests on what the authors term the Four Conceptual Pillars or Bridges of Understanding:

- The Transcendentals: Beauty, Truth, and Goodness

- Life After Death

- The One Supreme God

- Worthiness to Enter Heaven

I don’t have space to respond as I would like, so I will focus on #4, problematic given its western assumptions about “sin” and the related concept of “worthiness.” The authors make much of lines 27 and 28 of the “Cuicapeuhcayotl,” or Origin of Songs (quoted in part in my first post): “Could one be accompanied to the Flower World Paradise (in xochitlalpan in tonacatlalpan) who is nothing, afflicted, and who sins on earth? Indeed, it is the God of Far and Near (in Tloque in Nahuaque) who makes one worthy here on earth” (117) [emphasis mine]. Based on these lines, the authors argue that the speaker of the poem, and by extension all Nahuas, had recognized since ancient times that their sins barred them from Flower World unless the God of Far and Near (i.e., the Christian God) made them worthy. Two issues: 1) The Cantares Mexicanos, a collection of flower-songs of which the “Cuicapeuhcayotl” is the first, was complied in the sixteenth century by fray Bernardino de Sahagún and his indigenous Christian aides, so it’s possible the words and/or their meaning shifted when filtered through Christian transcribers; and 2) as Louise Burkhart points out, tlatlacolli, the Nahuatl root word translated as sin, is imperfect, because “though used for moral misdeeds, it also encompassed a broad range of accidents, crimes, and other breakdowns of established order. It failed to convey the sense of personal moral responsibility, with its accompanying burden of guilt, that sin bears in Christian theology” (Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico, 170). Further, the authors tie the idea of worth to the root word macehualli, generally meaning “commoner” or “man” in general, asserting that for the Nahuas, the term macehaul [sic] meant “one’s deserving or not deserving of the Flower World Paradise after death” (101). This interpretation applies a Christian gloss to an ostensibly precontact term; recall that the friars alphabetized Nahuatl for the purposes of evangelization, developing, in essence, ecclesiastical Nahuatl. Any definition applied to any Nahuatl word would have been necessarily applied in a post-Christian world, hence, one should use caution when defining precontact terms with postcontact glosses. Consider that Camilla Townsend glosses macehualli as a word meaning more than “commoner; etymologically, it referred to those deserving of the land, and hence of their own space in the polity” (Fifth Sun, 35). According to this definition, the idea of worth is tied to the land, not to the hereafter. The notion that Nahuas were awaiting redemption for their sins to become worthy to enter the Flower World appears repeatedly throughout the book, but it does not make sense in a Nahua world that lacks the concept of moral responsibility for personal sin that affects one’s worth in the afterlife. Despite their wide reading of Nahua culture and philosophy, the authors build their argument on shaky understanding of the Nahuatl world and thus pillar #4 falters.

Reading the Cuicapeuhcayotl chapter as the sea lions doze, turn, and bark

My primary critique is that the authors accept all printed sources at face value. As a history professor, I insist that my students interrogate primary sources, asking WHAT kind of document it is, WHO wrote it, WHY the author(s) wrote it, WHEN was it written/published, and WHERE was it written/published. The latter is a particularly critical question when dealing with early colonial indigenous-authored texts since their reflections on the Mexica-Castilian War and Christianity differ drastically depending on their altepetl (polity) of origin. Lastly, students must discern AUDIENCE, which is not always obvious. For example, who’s really the audience for El Requerimiento, a Latin or Spanish-language declaration meant to be read to newly-encountered native peoples to justify conquest if native peoples could not understand it?

Though Flower World Prophecy quotes Franciscan chroniclers and colonial, Christianized, indigenous historians without critical or historical analysis, the most egregious error is the authors’ use of the Coloquios, a reconstruction of conversations about Christianity that took place in 1524 between the newly-arrived Franciscans and the Nahua tlatoque (lords) and tlamatinime (wise men/priests). Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan humanist whose arrival to New Spain in 1529 means he was not present at these exchanges, fashioned the event as one conversation. Serving as the principal instructor at the Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco (founded in 1536), Sahagún became masterful at Nahuatl, co-authoring several important ethnographic sources with his trilingual (Nahuatl, Castilian, Latin) native students. After acknowledging that this 1524 exchange would have necessitated a translator, Flower World Prophecy quotes a portion of the Coloquios, then analyzes “why the Franciscans would use these Nahuatl terms [including in Tloque Nahuaque (the God of Far and Near)] to describe the One Supreme God” (156). What? Notes about this series of conversations would have been written in Spanish, because Nahuatl remained pictographic until the friars understood it well enough to alphabetize it. As Camilla Townsend astutely notes, “No one alive in 1524 could possibly have written in Nahuatl with the fluency that the document exhibits” (Fifth Sun, 136). The friars in 1524 did not choose these Nahuatl terms, Sahagún did decades later. This entire section (pp. 153-163) falters (which isn’t to say they couldn’t have used this source in another way if they had contextualized it!).

As a homeschooling mom, I had to fit in my reading whenever I could; given the theme of the book being a flowery paradise, I quite enjoyed that I read most of the book outdoors as my children played

The authors fail to properly contextualize the accepted Guadalupe account, Luis Laso de la Vega’s 1649 Huei tlamahuiçoltica, ignoring its grammatical errors and its relationship to Miguel Sánchez’s 1648 Imagen de la Virgen Mariía, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, nor do they engage with the fact that despite being composed in Nahuatl with Nahuatl expressions for Flower World and the God of Far and Near, its narrative follows the formula for the European genre of apparition literature as outlined in William Christian Jr.’s Apparitions in Late Medieval & Early Modern Spain (Princeton, 1981): a marginalized figure not immediately believed by Church hierarchy receives a sign to be believed. This fact is mentioned in the Story of Guadalupe, 18, a source the authors cite several times. The authors likewise gloss over details that would have resonated with colonial Nahuas, for example, mentioning that “[i]ndividuals from [Juan Diego’s] hometown of Cuauhtitlan came and assisted him at times in cleaning and sweeping the chapel [dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe],” but overlooking how daily sweeping for home deities was a precontact Nahua ritual. THIS would have resonated with the Nahuas, because it would have signaled an act reserved to the divine and indicated that others could participate in honoring the divine, i.e., God, to whom the Guadalupana points.

The authors end by marshalling evidence detailing how friars converted 8 to 10 million native peoples post-1531 after news of the Virgin’s appearance spread from altepetl to altepetl by way of flower-songs. The evidence might have convinced me, had I not been trained to interrogate the sources and had I not known that the story doesn’t end here, for the Mexican Catholic Church’s enthusiasm for native peoples waned in the sixteenth century. Whereas clergymen initially supported the ordination of native priests and in 1539 approved their ordination to the minor orders, by 1544 the clergy decreed native people incapable of civilization and Christianization without the Spaniards, and the First Mexican Provincial Council in 1555 forbid native ordination and decreed that native people must not touch the sacred vessels (Stafford Poole, “The Declining Image of the Indian Among Churchmen in Sixteenth-Century New Spain” in Indian-Religious Relations in Colonial Spanish America). This reality hardly supports the authors’ conclusion that the Nahuas’ “about-face was profound. They went from being immersed in heavy pagan ritual to becoming sincere, committed, and model Christians” (227) and that “[t]he friars were witness to a remarkable and resolute commitment from the Nahua as they wholeheartedly embraced complete Christian conversion” (228). [Side note: I’d be out of a career if Christianization of native peoples unfolded this way!] Significantly, internal dispositions are impossible to measure and scholars have moved away from discussing sincerity of belief. Even the humanistically-trained friars themselves recognized that conversion, from the Latin “convertere” or “turn around, transform,” was a daily decision.

Dining out with new and old friends

The theory expounded in this book is beautiful and the argument compelling. Were I not a historian specializing in the origins of Mexican Catholicism I might have been convinced. Perhaps I would have been convinced by the beauty of the argument itself. I love the idea that God prepared native peoples in the Americas to accept Christ (as I write these words, a jade hummingbird, inhabitant of the Flower World, hovers outside my window!). So, I suppose I accept the conclusion without accepting the premises.

I’ll end with something my 10-year-old daughter told me when I shared my thoughts with her. She said, “Mama, it’s too bad the authors of the book didn’t talk to you before they published it; you could have helped make it better.” I certainly would have enjoyed trying.

* A formal book review will appear in Fides et Historia later this year.