I have posted quite often here on the theme of American empire throughout history, and specifically its relationship to shaping religion. This post concerns a very useful and quite surprising way of approaching that topic.

Unlike other leading Western countries, the US has been quite ambiguous about its empire, and whether in fact we can even speak of such a thing. You don’t have to go too far back in history to find claims that the US was the only great power never to have had an empire, although few would argue that now. I like the title of Daniel Immerwahr’s fine book How to Hide an Empire (2019). In some eras of US history, to write about such an empire immediately alerted the reader that the work in question was going to offer a partisan and probably radical analysis, probably with the implication that the empire should be destroyed.

That brings me to a valuable tool that we can use for virtually any purpose, and with amazing results. This is the NGram viewer, which counts the number of occurrences of a given phrase in all the works digitized by Google Books – currently well over five million volumes. Briefly, you go to the page, and enter a word, name, or phrase. You choose the languages of the texts to be examined.

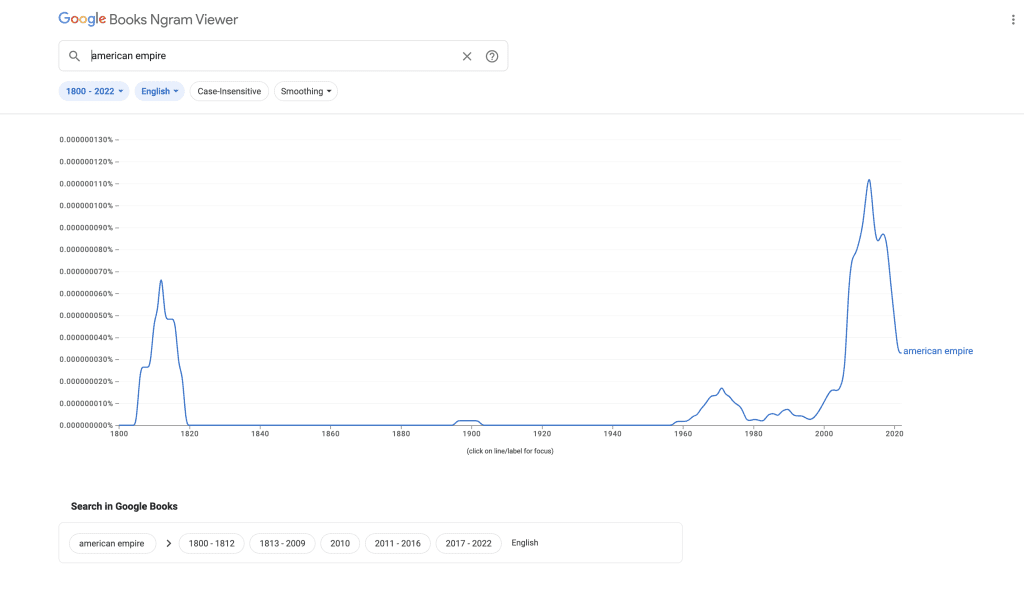

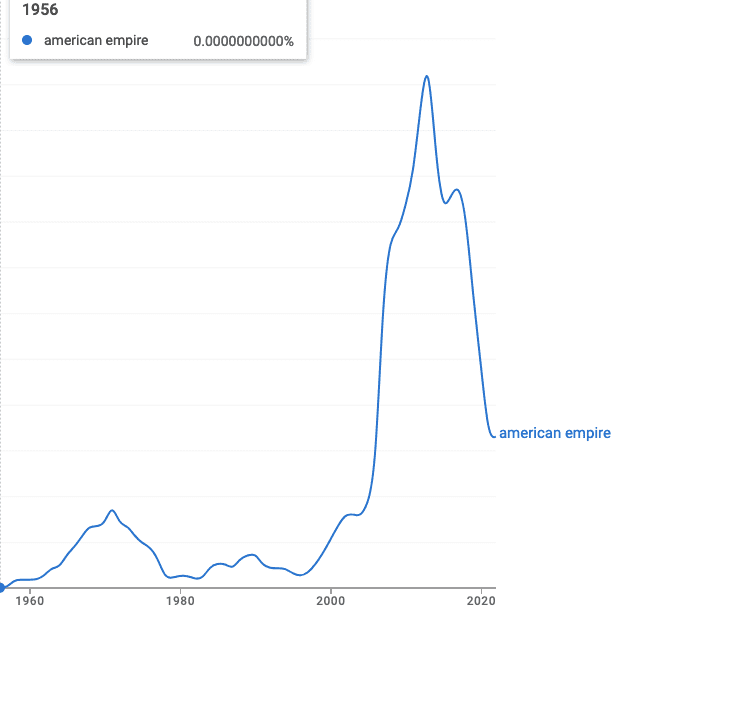

I entered “American Empire,” in English, and found the pattern represented here. You can also trace the line more precisely to identify particular years as peaks or troughs of usage.

Several eras show up very markedly:

1804-1819, with a peak in 1812;

1895-1903, without any obvious peak year;

1956-1978, with a sharp concentration in 1970-1971;

and then a real recent explosion from 2001 or so, with a dramatic surge in 2012.

Equally striking are the years of near or total non-usage, through most of the period from 1820 through 1895; and again 1903-1956. The period 1978-1996 was also relatively quiet.

In themselves, these numbers have to be used very carefully, as the data give us no information about how the phrase is being used. It includes historical usages, as well as polemic or controversial ones. Nor, of course, do we have any sense of the origins or nationality of the books surveyed, nor the authors. Having said that, some reasonable impressions emerge.

In the early nineteenth century period, Americans were very conscious of their rapidly expanding power and territory, not least with the Louisiana Purchase and the imminent prospect of expansion into other lands – Canada, perhaps, and the Caribbean. The focus around 1812 is very striking, and the subsequent decline might, conceivably, represent a dose of reality given the difficult course of the war with Britain.

The period around 1900 is very predictable, given the Spanish-American War, the vicious war that followed in the Philippines, and the fundamental national debate over the imperialism issue.

The 1970-1971 peak makes just as much intuitive sense. This was the absolute height of the protests about the Vietnam War, with surging movements for racial justice, all of which freely used the rhetoric of a general assault on American Empire. (Actually, it was more likely to be spelled “Amerikan” in those years, to sound suitably German and tyrannical). In popular culture, in 1970, Jefferson Starship produced the album Blows Against the Empire. Of course American empire was in the news, the headlines, and in books both academic and popular. Indeed, the whole notion of empires, viewed as evil and oppressive, was very much established in the culture. It was in 1973-74 that George Lucas was writing a science fiction script based on the resistance to an evil empire, with characters including a plucky princess, a heroic old knight, and some funny droids.

In the most recent period, we see two related trends. One is the upsurge of serious scholarly interest in the topic of American empire, which became thoroughly mainstreamed in the present century. Serious books on the topic proliferated. At the same time, we observe the consequences of the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Global War on Terror, and the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Again inevitably, it was difficult to describe these struggles except in terms of a crisis of empire, and indeed a general expansion of that entity. By 2012, criticisms of the ongoing Forever Wars had become very commonplace, while this marked this point at which the Obama administration was planning withdrawal and retrenchment: US involvement in the Iraq War ended in 2011.

I would argue that following the NGram evidence gives us a solid quantitative basis for discussing this topic, and potentially a very great many more.

One obvious point to make here is that the process does not map changing interest in a topic, but in a word or phrase that is used to describe it. It might be that the same problem is known by different terms in different eras, and the NGram viewer will map the terms, but not the thinking behind them. This is important for one area on which I work which is the long-term history of sexual abuse, in which the terminology for the behavior has changed quite a bit over time. If a given phrase no longer shows up in the NGram pattern, that may or may not mean that concern about the underlying issue has changed.

We have to be very careful, then, about any claims we make based on NGram evidence alone. But equally, it is difficult to think of areas of historical research in which it might not offer at least something of value.

By the way, as a very long time science fiction reader, I have to ask. Does Joe Haldeman receive a royalty payment every time some uses the phrase Forever War, which is taken from the title of his 1974 novel? He should.