My current work concerns the relationship between empires and the making and development of religion. Some of that connection is obvious – think of Christianity growing within the matrix of the Roman Empire, and then spreading worldwide through the missionary work of other later empires. But there are many other forms of influence and impact, and today I will talk about some other very modern patterns that occurred within an American imperial framework. Specifically, I will address the imperial dimensions of the much-discussed Protestant/Pentecostal explosion in the Americas.

How Empires Shape Religions

My most recent book was Kingdoms of this World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Religions (Baylor University Press, 2024). There, I described some of the ways in which the fact of empire shapes religions. Examples might include:

1.Intentionally or not, empires spread the religious forms that prevail in the metropolitan homeland to distant fringes of empire.

2.Empires foster speedier and more efficient means of communication and transport, in part as a means of preserving their power.

3.Empires enormously expand the geographical awareness and participation of subject peoples whose world maps would otherwise have been much more limited.

4.Empires bring awareness of conditions in remote lands to the attention of metropolitan societies, inspiring interest and perhaps imitation. People from the metropolis travel to remote societies and return carrying ideas and impressions. Empires send religions forth, and they receive them again.

5.Empires build cities in conquered lands, and these provides centers for disseminating ideas and beliefs.

6.Empires promote migrations and movements of peoples, often on a very large scale, bringing together peoples and ideas that never would have encountered each other.

7.Such migrations might bring subject peoples to the metropolitan homeland, or else to one or other of the new cities that the empires have developed on their occupied territories. In either setting, migrants encounter influential new ideas and beliefs.

8.The wars undertaken to advance or defend empires also accelerate the movement of peoples, whether as migrants

9.Empires spread common languages that promote the dissemination of ideas.

10.In all these processes, borderlands and marginal territories play an especially critical role.

I could expand this list considerably, but that will do for a start.

I make the obvious comment that in studying this topic, I am making no defense of empires, in theory or practice. I am just making what seems to me an irrefutable point about the huge role that empires and imperial contacts have in the history of religion, of all religions. In my book, I use case studies drawn from Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism, besides Christianity.

“In the long view, all world religions are imperial religions” (DISCUSS).

American Empires

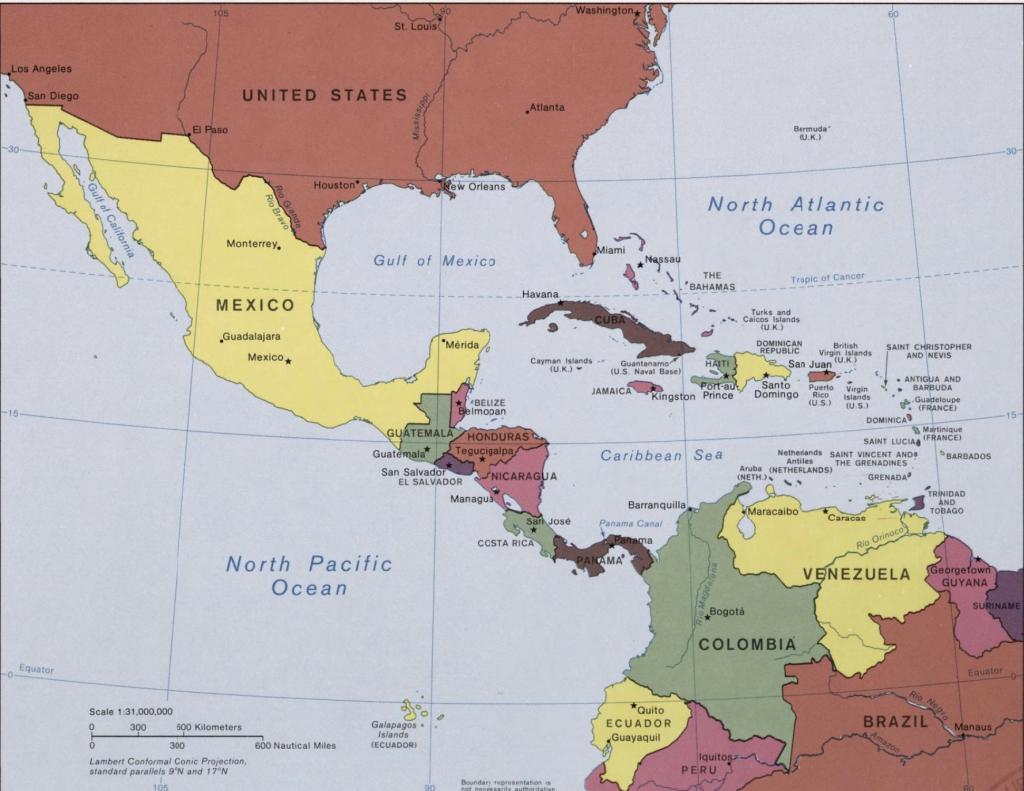

As I have noted in quite a few posts at this site, empire has been a constant and vital factor in American history, from the time of the British colonies through the settlement and expansion of the United States, and that process has often had religious manifestations. Most recently, I posted about the informal empire or quasi-empire that the US has long exercised in the Gulf/Caribbean region, the area we significantly refer to as the nation’s “backyard,” although lands such as Nicaragua never showed up on official imperial maps.

A hundred years ago, American forces directly occupied several territories in the region, including Nicaragua, although subsequently direct interventions have been rarer – the Dominican Republic in 1965, Grenada in 1983, Panama in 1990. Rule was rather exercised indirectly, through puppet regimes and dictators, and where necessary through the use of proxy forces and coups d’etat, directed fairly overtly by US intelligence. Much of the power was exercised through US corporations, such as the legendary United Fruit.

That was the background of the extraordinarily violent conflicts in Central America during the 1980s, which became integrated in the larger story of the Global Cold War, but which must also be seen as components of the long history of quasi-empire in the region. Cuba, of course, decisively seceded from the US sphere of influence, and Americans portrayed subsequent efforts at resistance or revolution as part of that Communist plot. In some cases that kind of domino theory had a factual basis, and in others, it did not. But the consequence was the savage wars in Nicaragua through the 1980s, a struggle which spilled over into neighboring nations. American policymakers viewed El Salvador as the likely next “domino” and the resulting war in this tiny nation killed up to 100,000 through the decade. Even that was dwarfed by the war waged by US-supported proxy forces in Guatemala, to which many apply the language of genocide. The three wars combined – in Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador – claimed at least 400,000 lives, mainly in the 1980s. That does not include victims of official killings and death squad activities in other countries in the region, including Mexico.

As in the Vietnam era, commentators on Central America drew freely on the language of American empire and colonialism, which seemed apposite given the ethnic composition of the region. In Guatemala above all, this was quite literally a latter-day Indian war, with notorious massacres of Native (Maya) populations.

I also note one point in passing, as it is so poorly remembered today. During the 1970s the US faced a significant danger from urban terrorist attacks organized by Puerto Rican revolutionaries closely aligned with Cuba. Literally, those forces viewed themselves as a revolutionary army struggling against the US colonial empire.

That whole Late Imperial aspect of the Gulf-Caribbean story is familiar enough, but we rarely pay attention to the religious impact.

Converting the Quasi-Empire

The Central American struggles of the 1980s – those wars on the frontiers of the US’s quasi-empire – transformed the religious realities of the societies that were directly affected by violence. To a degree that American policy makers barely appreciated at the time, this had most of the features of a religious war.

As is well known, one of the great facts in Latin American history in modern times is the phenomenal growth of Protestant and Pentecostal Christianity, and the consequent decline of the Catholic church. But that story cannot be understood except in the context of empire, quasi-empire, imperial wars, and the migrations they drove. Historically, the nations of Central America were not just Catholic but very traditionally so, and particularly among the rural populations of Native heritage. In the later twentieth century, American Protestant and Pentecostal missionaries enjoyed enormous success in the region, where large churches flourished, especially in the cities. In Guatemala, around forty percent of the people are now Protestant. This is not to say that such a transformation meant that local people were wholly accepting US ideas and beliefs, as churches quickly accommodated themselves to local interests and needs. But the mushroom growth of those congregations closely reflected the US influences that were so readily available in this era.

The religious change inevitably acquired a political dimension. Protestant advances inspired conservative American believers, who dreamed of a new Reformation in that area, and such hopes reinforced their anti-Communist fervor. The same changes also reshaped local political boundaries. At the bloody height of Guatemala’s civil war in the early 1980s, the military regime was headed by the evangelical general Efraín Ríos Montt, who closely allied with US counter-insurgency efforts. In effect, a state apparatus controlled by Protestants was targeting mainly Catholic Native peoples, a situation with many echoes of the European Reformation half a millennium earlier. The government actively supported Pentecostal growth in the countryside – which is not to accept the criticism that the movement was some kind of cynical creation of US policy.

Protestant and Pentecostal growth supplied the subtext for other conflicts and civil wars around the region. In southern Mexico, the revolutionary Zapatista movement of the 1990s often found itself fighting traditional-minded Catholic peasants.

The New Faith of the Cities

As conflict swept the countryside during the 1980s, rural populations migrated en masse to the cities, where they found succor in those Pentecostal congregations. If not wholly, Pentecostalism is par excellence a faith of cities, and of poor cities. In the 1960s, Tegucigalpa (capital of Honduras) had a population of around 250,000: today the figure is 1.5 million. The metropolitan area of San Salvador today stands around 2.4 million, and Guatemala City has some three million people. Of course Pentecostalism is flourishing: how could it be otherwise?

The wars of this era likewise drove migration to the relative safety of the United States, particularly in California. There are presently some four million immigrants from the region, 40 percent of whom are from El Salvador, 32 percent from Guatemala, the remainder from Nicaragua and Honduras. This too had major religious consequences. Many of the migrants remained faithfully Catholic, and they joined Catholic congregations in American cities, importing their familiar devotions and forms of the Virgin. But whatever their tradition might have been in their homelands, many other immigrants now acquired or renewed the Pentecostal faith that was so well established in poorer areas of US cities. Immigration thus vastly strengthened such churches in the US, but it also had a huge impact in the countries from which those migrants had fled. As migrants traveled to and from those countries in succeeding decades, they further promoted Americanized styles of worship and belief, which was most powerfully expressed in megachurches in the US mold. El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama all acquired such institutions, each with congregations running into the tens of thousands.

Just to take one example, the Misión Cristiana Elim Internacional (“Elim Central”) is based in San Salvador, in El Salvador, and its usual attendance is around 80,000. El Salvador is also home to the astonishing Tabernáculo Biblica Bautista. Or look at Casa de Dios, or Lluvias de Gracia, in Guatemala. Anything like those would have been inconceivable in the region before the religious transformation, which cannot be understood except in the context of the imperial wars.

Of Gangs and Churches

I just make one point here that is totally not intended to be disrespectful or trivializing. When scholars study the Central American immigration to the US, they often focus on the experience of criminal gangs, and that story has a surprising amount in common with that of Pentecostal churches. The two phenomena share a comm0n trajectory.

The Central American refugees and migrants who arrived in the US in the 1980s were concentrated in southern California, which was then in the middle of its urban gang boom. Black-derived gang subcultures and language were widely influential, and were popularized in hip hop. Largely for self-defense, Central Americans formed their own gangs, which became very powerful on US soil. The Salvadoran MS-13 was and remains a notorious example, with some 10,000 reputed members. After a few years, reverse migrants carried that whole gang culture back to their countries of origin, where such gangs came to dominate whole cities. Ever since then, gangs and gang influence have engaged in regular interchange and cross-pollination between US cities and the countries of Central America.

This is a complex story, but in the story of how influences travel, the analogies to churches and megachurches are obvious. And both stories grew out of war-driven migration.

Chile Too

The Central American experience makes us recall a closely parallel example from outside that region, which happened in the nation of Chile. Historically, Chile belonged to the British informal empire, rather than the American. In the 1970s, however, it was the Americans who intervened clandestinely to preserve their dominance in the Western hemisphere, and defend the larger quasi-empire against the Soviets. The 1973 coup and the regime that followed initially devastated Chilean society, immiserated large sections of the population and in the process transformed the cities. The consequence was that people were forced to depend on their own social and cultural resources, and Pentecostal churches boomed. Today, the most Protestant nations in Latin America by population share are Chile and Guatemala – an interesting duo.

In both cases, we are looking at a religious revolution, and one driven by Late Imperial conflicts and rivalries. As you observe the process I have described, just go back to the list of “empire factors” that I outlined at the beginning here, and see how closely at least most of them apply.

I will have lots more to say about these topics next time, among other things addressing the impact on Catholics in the US itself.

AND ON A TOTALLY DIFFERENT MATTER, which, well, actually is pretty closely related to the main subject of this post. It’s all about marigolds.

The New York Times has a lovely piece about Hinduism and How Marigolds Became a Flower for Weddings and Funerals, which tells us a great deal about the linkage between empires and religion. The story begins:

In the holy Indian city of Varanasi, the bodies of the dead are draped in garlands of marigolds before being cremated on the banks of the Ganges River. According to Hindu teachings, marigolds embody purity, strength and new beginnings, which means that they feature in rituals of all kinds, from political rallies to sacred festivals to weddings. In cities and towns across India, vendors display them heaped into small mountains or strung into ropes, which are used to adorn the necks of newlyweds or to embellish ceremonial altars.

Wonderful, but where do marigolds come from in the first place? They originated in Mexico, where the Aztecs used them in funerary rituals associated with the death goddess Mictecacihuatl. That custom is widely recalled in modern Day of the Dead celebrations. Those flowers were then trafficked widely by the Spanish and Portuguese after the Habsburg imperial conquest of that land. Those trophies of empire reached India, presumably through the Portuguese imperial settlements there, and were then distributed widely through the subcontinent. So widely in fact that they came to be integral to Hindu practice, and were commonly viewed as an ancient and fundamental element of the faith.

That is how empires work.