My current work involves the critical role of empires in making and reshaping the world’s religions. I recently published the book Kingdoms of this World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Religions (Baylor University Press, 2024), and currently I am working on the specifically American aspects of that issue. As you will see from a couple of recent posts at this site, I argue that this imperial dimension is critical for understanding many aspects of the American religious tradition, including something as basic as religious liberty and the nature of the denominations that became most successful, not to mention the New Age.

In the next couple of blogs, I want to explore the impact of what I call “Late Empire” on those religious trends and forms. But to do that, I have to do something really basic, which is to decide where we find the limits of anything that we can reasonably call the American Empire, and that is a harder task that it appears. Formally, the US has only a few territories that conspicuously survive as vestiges of older imperial outreach: Puerto Rico and Guam come to mind. But matters get more complicated when we look at many regions which have de facto been within the span of American power for a very long period, even if they were never officially part of that realm.

To leap ahead, I will argue that we can legitimately apply the language of empire and imperial struggles to events such as the wars in Central America during the 1980s, and we must discuss the religious consequences for the US. If that argument seems a bridge too far right now, bear with me.

Informal Empire

Empire in general is currently a very lively area of scholarship throughout the world, and one critical aspect of that is “informal empire.” This describes a situation in which a Great Power utterly dominates a smaller nation – mainly in economic terms, but also politically and culturally. To all intents and purposes, that small country is dependent on the Big Brother, but for various reasons, the Brother does not choose to annex it formally. The classic examples that gave rise to this concept were Latin American. For the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries, Argentina and Uruguay, for instance, were wholly owned subsidiaries of the British Empire, but annexation was never on the table because it would cause a nightmare confrontation with the US, and the Monroe Doctrine. The idea applied much more formally, including in the Persian Gulf, where local kingdoms were well aware that they lay within the British sphere, but that role is never reflected in the world maps that conveniently colored British possessions a bold pink. Some lesser states did ask for full admission to the empire, but were politely declined.

All empires, ancient and modern, have exercised such informal power, commanding varying degrees of direct control. Normally, the lesser power could do most things by itself on an internal basis, but the Big Brother controlled the levers of the economy, dominated investment and the economy, and only a very thin line separated local from imperial elites. Sometimes, power was exercised through corporations and business interests that had an intimate relationship with the imperial government.

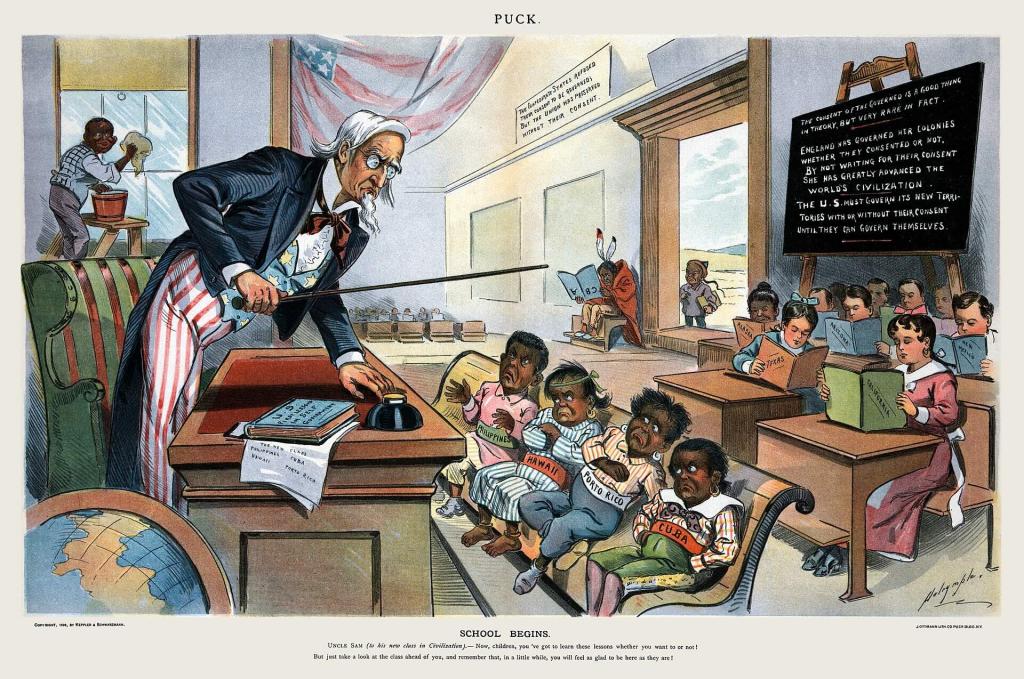

Informal empire often involved a great deal of what later generations would call “soft power,” dominating the cultural and educational life of the smaller state, whose elites avidly followed the ways of the imperial metropolis, and might send their children to learn in their great schools and colleges. If those peoples are not formally subjects of the great empire, then that empire, and no other, is the one they identify with.

The Japanese exercised this kind of power in China during the decades when they were not directly ruling the country. French, Germans, and Russians all behaved accordingly in their particular regions, which were often located quite close to areas of formal control. Over time, informal empire easily transitioned into formal rule, but it did not necessarily do so.

“America’s Backyard” as Informal Empire

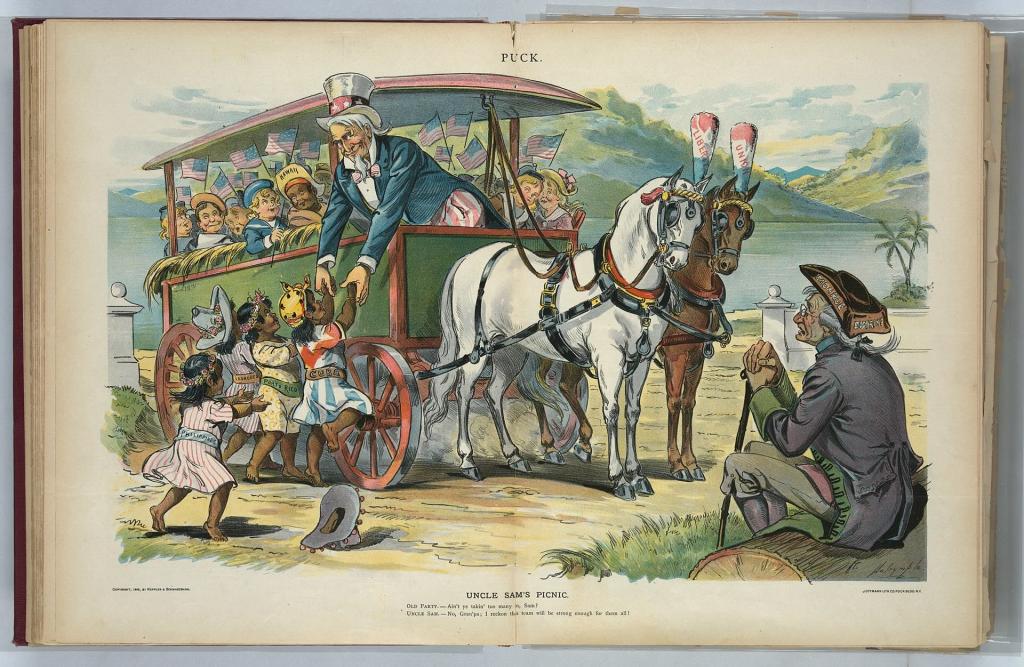

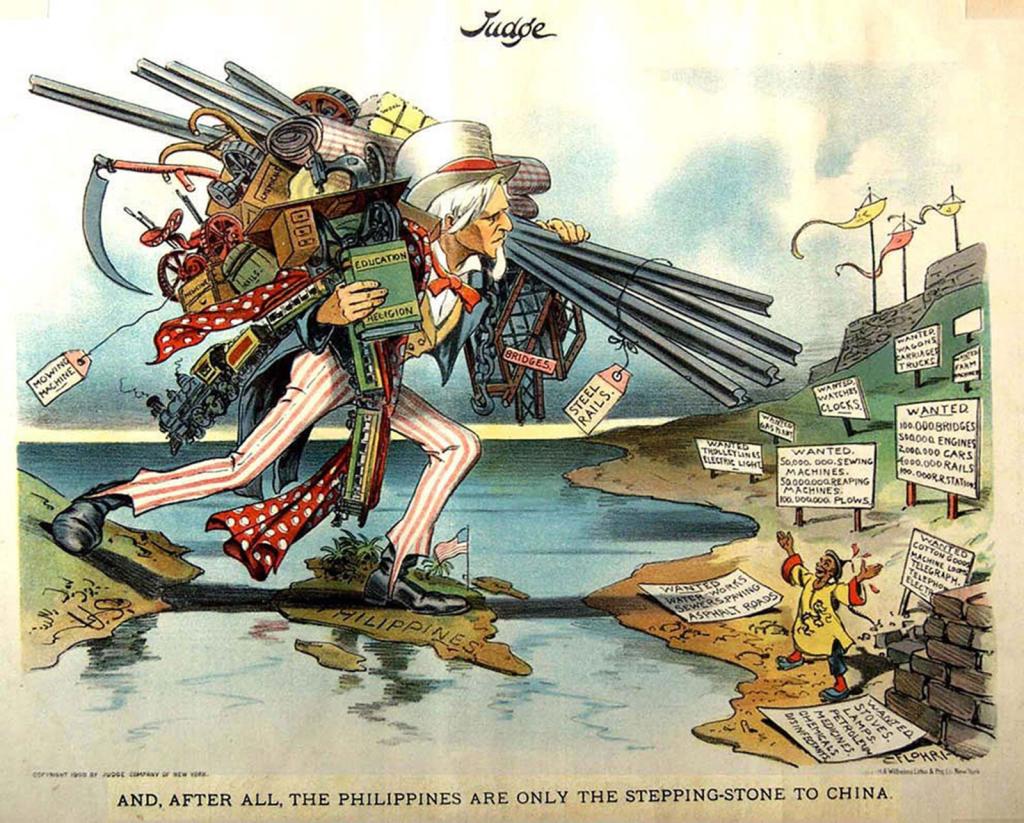

With that in mind, we think of the American empire, as has been very well studied by such scholars as Daniel Immerwahr and A. G. Hopkins (see the reading list below). In formal terms, the US overseas empire emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, and its most spectacular acquisition was the Philippines. But in terms of informal empire, that power stretched vastly further, and began earlier. For some decades before the 1890s, American informal power in Hawaii grew steadily to reach near-total hegemony, which in turn transformed into formal, official, imperial rule – and ultimately, to statehood.

It is hard to deny that a similar informal American rule extended over the whole Gulf/Caribbean region, except for territories that were clearly designated as the possession of some other empire, such as the British or French. And those claims and aspirations had a very long pedigree. Think of it as the quasi-empire.

I offer an example. Hard though it is to recall these days, back in the 1980s, the nation of Nicaragua was a desperate concern for American policy-makers, and that country’s affairs featured perilously on the global stage. For several years, the issue of supplying aid to US-backed anti-Communist guerrillas, the Contras, was one of the leading issues in American politics, and Reagan administration efforts to get around Congressional restrictions came close to getting the president impeached in 1986-87. Nicaragua-related activism and social movements were very evident in the nation’s religious and political affairs. Again, we tend to forget how critical Central American debates were to the American religious politics of the 1980s.

At the time, the administration decried the Nicaragua crisis as arising from Soviet and Cuban dabbling in the US “backyard,” but the whole story had a deep historical background, and one rooted in empire. To over-simplify, the British colonies in America had covered not just the thirteen colonies but also stretched into Canada and the Caribbean, and from the earliest days of the American republic, the new nation’s leaders had never totally believed that this “vast” territory would not sooner or later slip into American hands. Such hopes grew mightily during the slavery controversies of the Antebellum years. Entrepreneurs repeatedly tried to force the hand of their own government by launching military adventures into neighboring societies, creating a pro-US secession movement, and ideally laying the groundwork for annexation. Such an enterprise worked splendidly in the Texas Revolution of the 1830s, but other interventionists – filibusters in the language of the day – met disaster, in Cuba, and even in Canada.

In Nicaragua, the notorious figure was William Walker, who was declared President of that country, before ultimately being executed in 1860. In 1987, that story became the subject of the film Walker, with its deliberate anachronisms (helicopters!) and its explicit references to the Contra debates of the Reagan era. Nicaragua had a special appeal for Americans because of the lengthy dream that it m might provide the setting for a great canal to unite the Caribbean and the Pacific, as was eventually built in Panama.

American Empire Building: The Twentieth Century

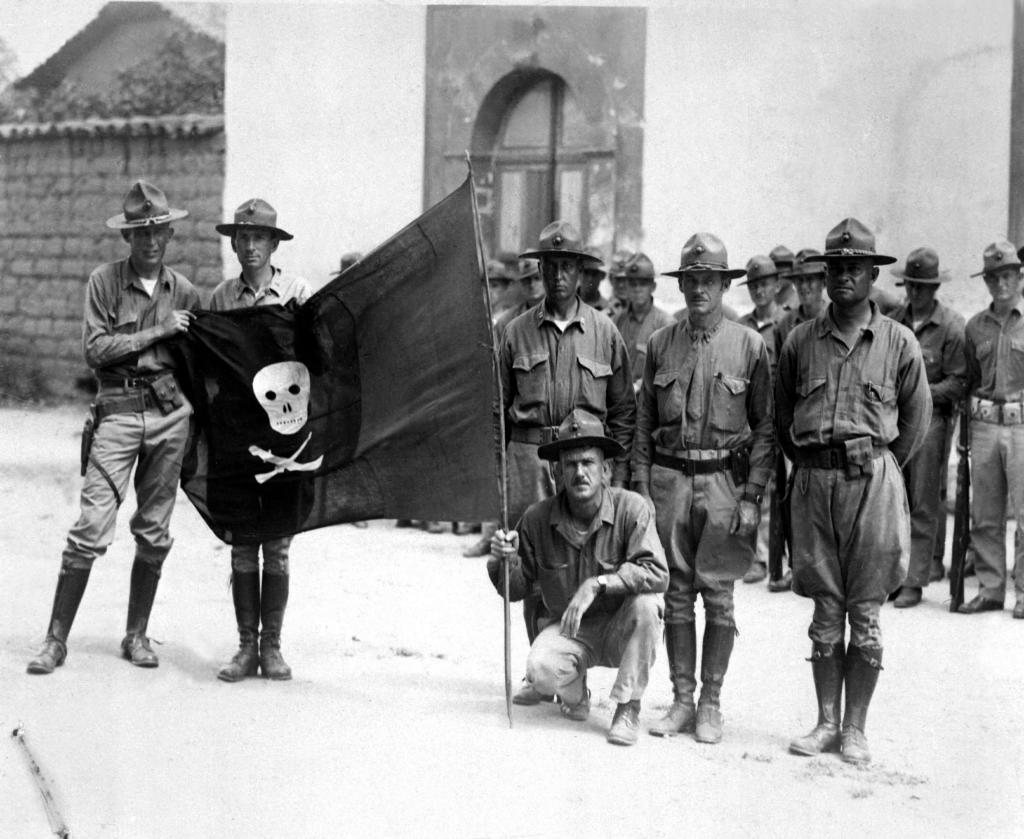

But filibustering and like activities assuredly did not end with the fall of American slavery, and the most aggressive expansionism occurred in the early twentieth century. On various pretenses, US forces occupied several nations in the Caribbean and Central America and ran them as protectorates for lengthy periods. This was the fate that befell Nicaragua for most of the period from 1912 through 1933; Haiti from 1915 through 1934; and the Dominican Republic, from 1916 to 1924. That does not include the nations that theoretically retained independence, but did so chiefly through the alliance of local elites with major US commercial concerns, such as the United Fruit Company in Guatemala and Honduras. It was in 1904 that the US writer O. Henry invented the term “banana republic” to characterize such arrangements, and the various conflicts and interventions of these years are commonly termed the “Banana Wars.” In 1917, the US acquired the Danish West Indies from that country, albeit by purchase rather than armed might: they duly became the US Virgin Islands. Even in Mexico, US forces launched a military expedition against the port of Vera Cruz in 1914, and then undertook a sizable invasion of northern regions in search of the forces of Pancho Villa in 1916-1917.

In the 1930s, the New Deal administration of Franklin Roosevelt systematically withdrew from direct occupation of these southern territories as part of a general “Good Neighbor” policy to Latin America. Even so, local proxy regimes ably defended US interests through long-established dictatorships associated with such notorious names as the Somozas in Nicaragua, Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, and Batista in Cuba. The Somoza dynasty held power in Nicaragua until 1979, when the collapse of the that regime opened the door to the left-wingers who so troubled the Reagan administration, the Sandinistas. Those leftists took their name from Augusto Sandino, who had led a rebellion against the Americans and their puppets before being killed in 1934. The National Guard through which the Somozas exercised power was a primary source of recruitment for the new anti-Communist Contras.

If Nicaragua never featured on any official map of the American empire, it is very difficult to see it as anything other than a component of that entity, albeit an informal possession. Nor can we easily mark a point at which that imperial domination ceased, to be replaced by the interaction of two sovereign states. Nicaraguan history throughout the twentieth century followed that same imperial, or quasi-imperial, trajectory. How can we not see the wars of the 1980s as a direct continuation of older imperial dreams and nightmares, a struggle of the Late Imperial world?

Cuba offers similar long continuities. In fact, it was a near-miracle that the United States never managed to absorb Cuba into its national territory. Jefferson had envisioned such a prospect as early as 1805, and in 1823, John Quincy Adams thought it was not only desirable, but natural, a matter of destiny, and even of objective science. As he said, “There are laws of political as well as physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground.” Once Cuba was detached from Spain, it could “gravitate only towards the North American union.” It was “ripe fruit.” In the decades to come the US made six separate proposals to purchase the island, culminating in conquest in 1898. A crisis in the 1870s very nearly led to Ulysses S. Grant’s administration taking the island from Spain, much as the US actually did a quarter century afterward. (Around the same time as that earlier Cuba crisis, Grant came very close to acquiring the Dominican Republic as a US territory). And although Cuba remained notionally independent after the US victory over Spain, its constitution specified that the US had the right to intervene in the nation’s affairs, and to exercise control over its finances and foreign relations. In effect, the treaty terms of the Platt Amendment made Cuba an American protectorate. Later, as in the case of Nicaragua, the US exercised power through a surrogate regime, but this was decisively overthrown by the Communist victory in 1959.

I would love to tell you that these informal adventures in such so-called “banana republics” agonized many Americans during these years, but I would be struggling for evidence. If those places existed at all on the American mental map, it was as tourist territory, where the laws about sex, alcohol, and drugs were much more easygoing than at home. In 1946, Guy Lombardo had a major hit with the song

Managua, Nicaragua is a beautiful town

You buy a hacienda for a few pesos down…

In the same year, Bing Crosby sang “I’ll see you in C.U.B.A.”:

The Blank Check

From the late nineteenth century through quite modern times, the US regarded its south-facing “backyard” as a natural possession, an informal empire, and that attitude explains some seemingly odd political responses. After 1898, the US had a fierce debate over the rights and wrongs of imperialism, in which the great opponent of empire-building was William Jennings Bryan, whose views often resonate with modern liberal sensibilities. But as Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson, it was Bryan who actually directed US interventions in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti, and with no obvious moral qualms: in the last instance, all that struck him as odd about the country was to find “N—-rs speaking French.” By implication, such ventures had nothing to do with empire. In their backyard, the US had something like a blank check to intervene in these territories, which were natural and indispensable adjuncts to US national territory.

In 1914, Bryan praised President Wilson who he had “opened the doors of all the weaker countries to an invasion of American capital and American enterprise.” That is a fine definition of informal empire. And as to when that situation ended…. when? Well, we might ask Ronald Reagan, or maybe the first President Bush, who invaded Panama in 1990.

So yes, we definitely need to study American informal empire, and to explore its dimensions around the world. The main area in which Americans hoped for informal empire was China, and there is a whole Middle Eastern story here also. And with that in mind, this opens the door to a lot that I have to say about the extensive religious implications of American imperial history.

More next time.

Some Selected References

Robert D. Aguirre, Informal Empire: Mexico And Central America In Victorian Culture (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2005)

Gregory A. Barton, Informal Empire And The Rise Of One World Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Matthew Brown, Informal Empire In Latin America: Culture, Commerce And Capital (Oxford: Blackwell 2008)

Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, ed., The Japanese Informal Empire In China, 1895-1937 (Princeton University Press, 1989)

A.G. Hopkins, American Empire: A Global History (Princeton University Press, 2018)

Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York: Macmillan, 2019).

Thomas J. McCormick, China Market; America’s Quest For Informal Empire, 1893-1901 (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1967)

Stephen McCullough, The Caribbean Policy Of The Ulysses S. Grant Administration: Foreshadowing An Informal Empire (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018)

Jessie Reeder, The Forms Of Informal Empire: Britain, Latin America, And Nineteenth-Century Literature (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020)

Daniel Silverfarb, Britain’s Informal Empire In The Middle East: A Case Study Of Iraq, 1929-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986)

David Todd, A Velvet Empire: French Informal Imperialism In The Nineteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 2021)

I have a sizable working bibliography on US Empire here.