I have been posting on the religious dimensions of empire in American history, and I have stressed how the nation’s imperial expansion from earliest times must be seen in that imperial context. Over the past decade, one very influential approach to that story has been the idea of “Vast Early America,” which is commonly represented as a hashtag, #VastEarlyAmerica. Today I will describe the core idea and the debates that it has inspired, and next time, I will look at some implications, chiefly in terms of religion(s) and faith(s).

The debate over “vastness” owes much to a critique of current scholarship on early America that the magisterial historian Gordon S. Wood published in 2015. The term “early” is flexible, but for present purposes, let us say it runs up to the 1820s or so. Focusing on the flagship journal, the William and Mary Quarterly, Wood was disturbed at what he saw as the excessive attention paid to non-US regions (especially the Caribbean and Africa) and to subaltern peoples. Where in all this, he asked, was the central narrative of the formation and development of what would become the United States? Responding to that critique, other historians argued that the standard focus on the development of the British colonies into the US was so constrained and presentist as to be profoundly distorted in terms of understanding past realities. Diversity and inclusion were not just political buzzwords, they offered the only realistic means of understanding that larger – vaster – American history, or histories. In the words of Karin Wulf, one of the great exponents of this theme,

increased attention to diverse people (women, enslaved African Americans, Native Americans) and places (California, the Caribbean, West Africa, Atlantic port cities) takes us outside the framework that marches us from Colonial (British) America to the Revolution to the early United States.

These ideas were neatly summarized by the term “Vast Early America,” which received an effective branding as a much-used hashtag. To quote Wulf again, this is shorthand “for the chronologically, conceptually, geographically, and methodologically capacious early American scholarship that has characterized the last decades.” The concept has been much used in subsequent writing over the past few years, notably in a special issue of the William and Mary Quarterly in 2021. The same idea dominated a more recent special number this past January on “The End of Early America.”

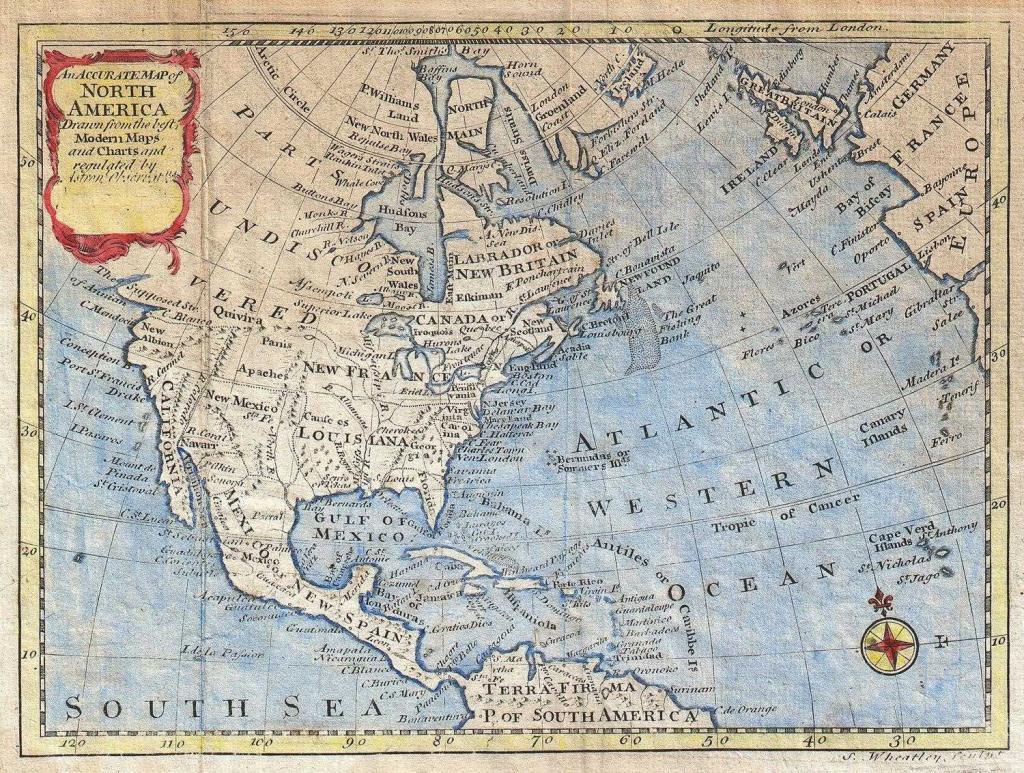

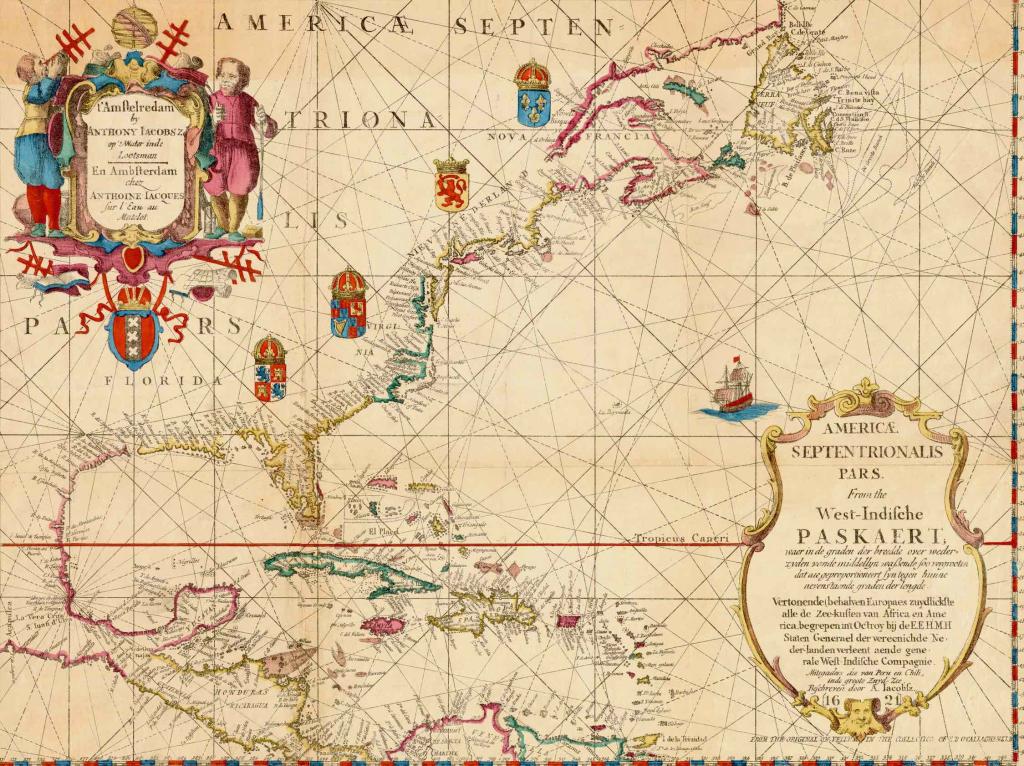

The appeal of “vastness” is obvious enough if we consider the alternatives. Think for instance of an older vision of “America” growing out of the British-ruled east coast and spreading into the continent, duly illustrated by maps in which regions were illuminated only when settled by those those British, Irish, and North European pioneers. Before that point, by implication, those regions and their peoples scarcely existed. They assuredly had no history worth mentioning.

The problems with such an approach are obvious, in terms of what it covers, and what it omits. As I have suggested in earlier posts, early (and early national) American history makes next to no sense unless we see it as part of a subcontinental reality that includes the Caribbean and territories that eventually become part of Canada – notably Québec and Nova Scotia. Seeking to correct that distortion, more recent historians used the model of the Atlantic world or worlds, whether British, French, or Spanish, and incorporating the vital idea of the Black Atlantic. Again, these visions demand that US history be placed in the context of events in Bristol or Bermuda or Freetown. Broadly Atlanticist accounts became very common in the Early American literature around the turn of the present century.

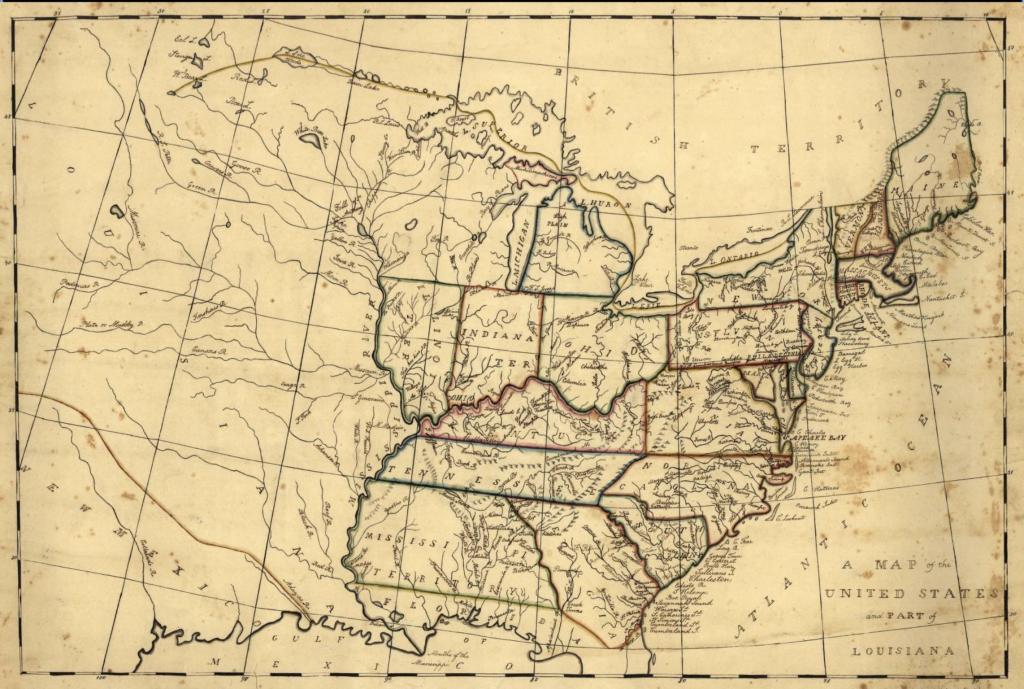

But was even such an expansion sufficient? Above all, what about Native peoples? As we know in retrospect, by the early nineteenth century, Natives were on the verge of suffering catastrophic dispossession, but that was in no way evident before that point. Suppose we write a “vast” history of America in 1750 or 1800. Our first problem concerns borders, which of course determine the limits of the story we are trying to tell. Should our history be confined to topics within the limits of the Lower Forty Eight states? Those borders were not finalized until the 1850s, however often we treat them as representing some kind of metaphysical reality that were always intended to be there.

Put another way, how far should our awareness of the later phenomenon of the US nation state determine how we understand earlier eras? To quote Karin Wulf again, “The connection to the early United States has long made early American history both terribly compelling and particularly vexed. It answered the question of whether history is about people, place, or polity, with a resounding affirmative only for the last.” Yes, we properly write about the evolution of the British colonies and their move to revolution and nationhood. “But, then, does that mean American geography only turns westward, over the Appalachian Mountains and on toward the Pacific once the United States officially claimed more territory? As a shorthand for this conundrum, does California have an early American past?” [my emphasis]. What a wonderful question.

If we visualize the regional focus of articles published in the William and Mary Quarterly between the 1940s and 2008, then “North America looks like a beachball made up of the East Coast with a bit of seaweed clinging to its left side representing every other region.”

And again, what does this say about Native Americans, whom we often present as if their doom was somehow inevitable, and as if they were serving merely as placeholders for the white settlement that was to come?

Although precise numbers are very shaky, Claudio Saunt suggests that if we look at the territory of the Lower Forty Eight in the mid-eighteenth century, then around half the overall population was still Native, 40 percent European, and ten percent African. That is eight or nine generations after the time of Columbus. And the obvious question then arises: just why should we be so concerned with focusing on the later territory of the US? Native peoples traveled freely across what would some day become those borders, into what we think of as “naturally” constituting Canada or Mexico, where other Native populations were abundant. Of course the Native victors of the Battle of the Little Big Horn fled into Canada to seek British refuge, and the British experienced agonies trying to persuade them nicely to go home, without starting an all out war with the US. Even in modern times, Mohawk and Ojibwe people, for instance, have been very slow to convince that they should pay much attention to the international border separating the US from Canada. Just ask the Border Patrol and hear them groan.

These Native peoples were moreover very diverse in their cultures, their attitudes and their behaviors, a point amply illustrated by the responses of various tribes and nations to such tumultuous events as the American Revolution. To take just one region, Michael Witgen shows that around 1805, the population of Michigan would have included around fifty thousand Natives and five thousand Whites. How then can any reasonable account of that region concentrate solely on the attitudes and politics of that quite small White minority?

When I approach such a situation from my own historical background, one analogy occurs to me overwhelmingly, and I am surprised that it is not cited more often in the contemporary “vast” American literature. Maybe it is just too famous and too familiar. In the 1930s, French historian Fernand Braudel began to write a history of the great battle of Lepanto, in 1571. As he went on, he realized that he had to expand the project greatly to survey the long political history that had preceded the battle. And gradually, he realized that any credible account must include the foundational realities of Mediterranean societies, in terms of factors of landscape and environment, social and cultural themes, very diverse histories of everyday life. His planned Lepanto monograph morphed into a sprawling and massively influential text originally published in France in 1949, and translated as The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. I quote:

Braudel was interested first and foremost in the environment in which the peoples of the Mediterranean basin lived: its mountains and plains, the sea, its rivers, roads, and towns. He combined the almost fixed rhythm of “geographic time” with the rapid rhythm of “individual time” and the movement of peoples and their ideas. This research led him to study such focal points of human activity as Venice, Milan, Genoa, and Florence, and the exchanges that took place between them.

You can think of plenty of equivalent focal points in the North American context, places where worlds and cultures and races intersect, including New Orleans. My own prime example in early America would be Michilimackinac and its surrounding region, which is now in Michigan. Its history is astonishing.

In our modern terms, we can think of Braudel as the inventor of historical vastness, and his methods are widely applied. In modern times, this has become the standard way of writing the intertwined histories of the Indian Ocean.

One insight of his still bears repeating. If you want to understand a geography, any geography, by all means look at a map – but defamiliarize yourself with it, so you see its connections for the first time. Make it strange. Turn the thing upside down! Only thus, for instance, will you see with a shock of recognition, that the southern coast of the Mediterranean is linked to the worlds of North Africa, stretching deep into the Sahara. And just how intimately Northern Italy is connected to the Rhineland, and the Low Countries. It is a brilliant tactic, and it still works. Try applying it to North America. Go ahead.

Hmm, it’s harder to see those national borders, isn’t it? That is definitely true along that very lengthy Pacific coast. Do you see those enormous Plains at the heart of the continent, which spread as deep into Canada as the US? And the Caribbean really does emerge as what some have indeed called an American Mediterranean. Oh my, New Orleans looks more central to American realities than we usually think. And again, so the Great Lakes have a whole big northern side that is beyond US borders! Who knew? Did that northern region actually mark crucial territory for whole Native cultures and peoples that we normally assign to the US side of the Great Lakes? (It did).

I have already suggested that students of early American history should have to take a course on Caribbean affairs. And also one on Canadian history?

In terms of my own interests, one lesson that emerges powerfully from the “vast” approach is the critical and enduring significance of empires, which in very few instances had any particular relevance to political borders as we know them today. At a minimum, that means the British, French, Spanish, and Russian realms (the Swedish and Dutch tried hard). Of its nature, vast American history – and certainly not just in its earliest manifestations – is imperial, or it is nothing. On five or so occasions between 1814 and 1930, American governments had to think very seriously indeed about the prospects of warfare with the British empire, and in that scenario both the Caribbean and the northern borders would have been in play. Arguably, not until the 1940s could the US afford the luxury of pursuing its destiny without the threat of serious conflict or competition with that neighboring empire.

And just at that point, the country then faces the new nightmare of another empire being built on its doorstep, in the form of expanded Soviet power, most alarmingly in the Caribbean. Just when you think you have kicked the British out, in comes the next wave of would-be empire builders, with all their military bases and intelligence stations. Hmm, so when was America anything other than #Vast?

If you are an American historian, you may think you are not interested in empires. But empires are interested in you, and shaping everything you study.

So how do you reach any kind of truth about early America? You might follow Goethe’s advice. To go forward into the infinite, you pursue the finite in all directions. You ignore borders.

Next time, I’ll explore the very substantial religious dimensions of this “vast” approach.