I have been working on the topic of empires and their religious dimensions, and my new book Kingdoms of This World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Religions will be published next week. That book ranges very widely through time and space, but even so, it left a great deal to be said about one particular imperial setup, namely that of the United States. As I have argued in past posts at this site, it is impossible to understand the United States except as a classic empire, and by that, I include the emerging nation that spread across the Lower Forty Eight, even before it formally ventured into overseas empire-building in the 1890s. You can find and download a sizable and steadily expanding bibliography that I have compiled on that topic.

There is a huge amount to be said about the religious dimensions of that American imperial project, and I am presently mulling whether that might be a whole second book in its own right. In a sense, it is just too big a project because it could potentially include the whole of the nation’s religious history from the foundation up. But there are a couple of significant topics that I think deserve special attention, and I will highlight these here.

A simplistic stereotype of the empire/religion linkage imagines empires forcibly spreading their own beliefs onto unwilling Native recipients, who are thereby saved from Heathen darkness, and who in the process lose their cultures and (often) their lands. That certainly can happen, and the cynical uses of religion for imperial purposes have often been analyzed, and satirized. But other interactions are much more complex. Empires can for instance enable the spread of religious systems of which they totally disapprove, the obvious example being how the Roman Empire quite unintentionally created a world safe for Christianity. Also, empires can on occasion become “infected” with the faiths of which they initially disapprove, as those faiths develop roots in the metropolitan homeland. Subject religions can become official religions. However hard I strive to avoid the phrase, I just can’t: in religious terms above all, empires really do strike back.

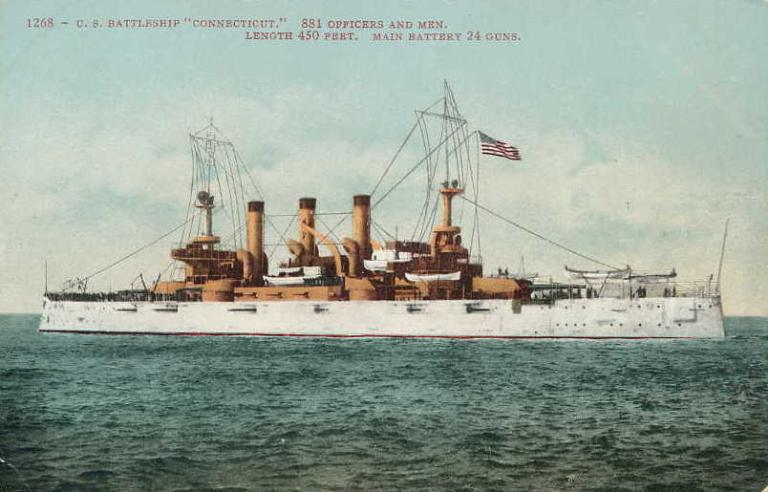

Look at what happened in the US in the generation or so following the Spanish-American war of 1898. This marked the full headlong plunge into empire in both the Pacific and the Caribbean, a vision reinforced by the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914. In 1907-09, the US Navy sent its Great White Fleet on a global journey to proclaim the arrival of the country’s new imperial presence. We can explore the religious consequences of that story in terms of expanding efforts by American missionaries in the Philippines and elsewhere, and the spread of American styles of Protestant Christianity. Of course you can’t write the history of American missions without confronting the idea of empire and of imperial ideologies, with all their racial connotations.

Consider the imperial impact on the US itself. These developments promoted a population boom in Southern California, which attracted a large number of migrants from the northeast and Midwest. Los Angeles grew from 50,000 residents in 1890 to 577,000 by 1920. A great many of those people were committed to various experimental and sectarian forms of faith, and they happily built headquarters and compounds where land was cheap, and regulation very mild. Also, many migrants moved for health reasons, seeking hot and dry climates, and those sick populations were very open to hearing the messages of alternative healers. In consequence, the emerging Southern California became legendary as a center for what we would call cults, and a booming ecosystem of alternative and esoteric religions.

I stress that this was not the first American encounter with “Oriental” religions. As I will discuss in a future post, American intellectuals such as Thoreau and Emerson had been fascinated by Indian faiths since the 1840s, drawing on what the British had discovered in their new imperial possessions. At this stage, Americans were drawing vicariously on the experiences of other empires. In the 1870s, the vital new movement of Theosophy disseminated Buddhist and Hindu ideas through the West, a process further continued following the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893. Esoteric, Asian, and mystical faiths now enjoyed a huge vogue in the US.

This world found its capital at Point Loma outside San Diego, where the great Theosophical settlement flourished from 1899 through 1946, serving as a kind of global metropolis of the mystical and metaphysical. That settlement was very well established in 1918 when the US began the construction of what became the crucial naval base of San Diego, which represented the central fact in American military empire in the Pacific world.

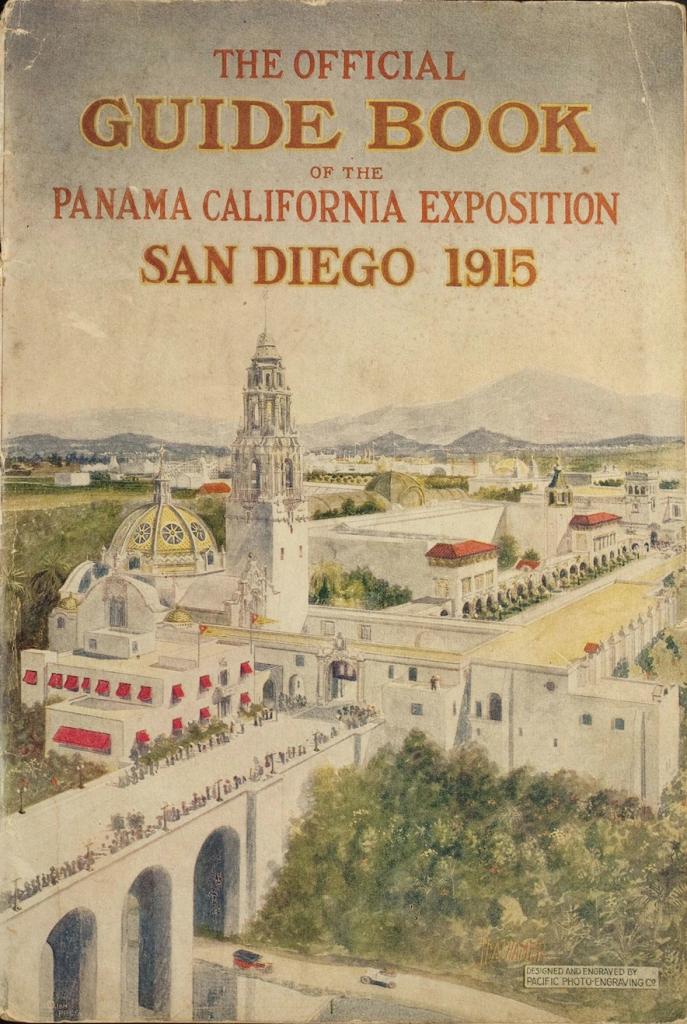

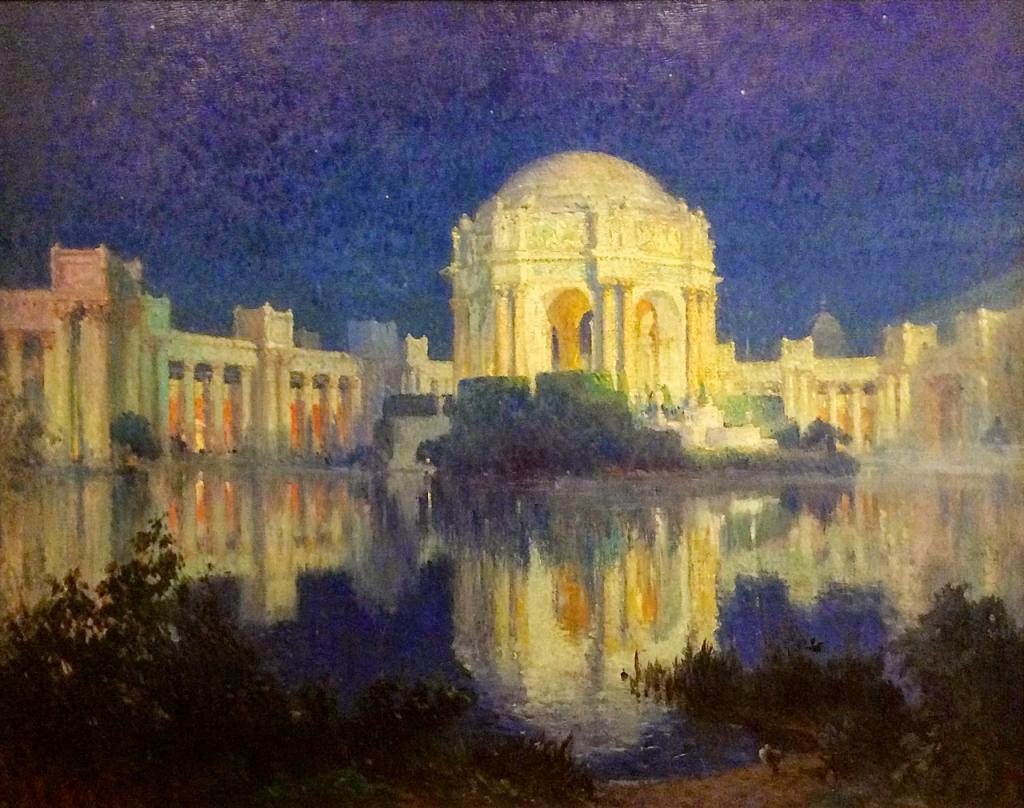

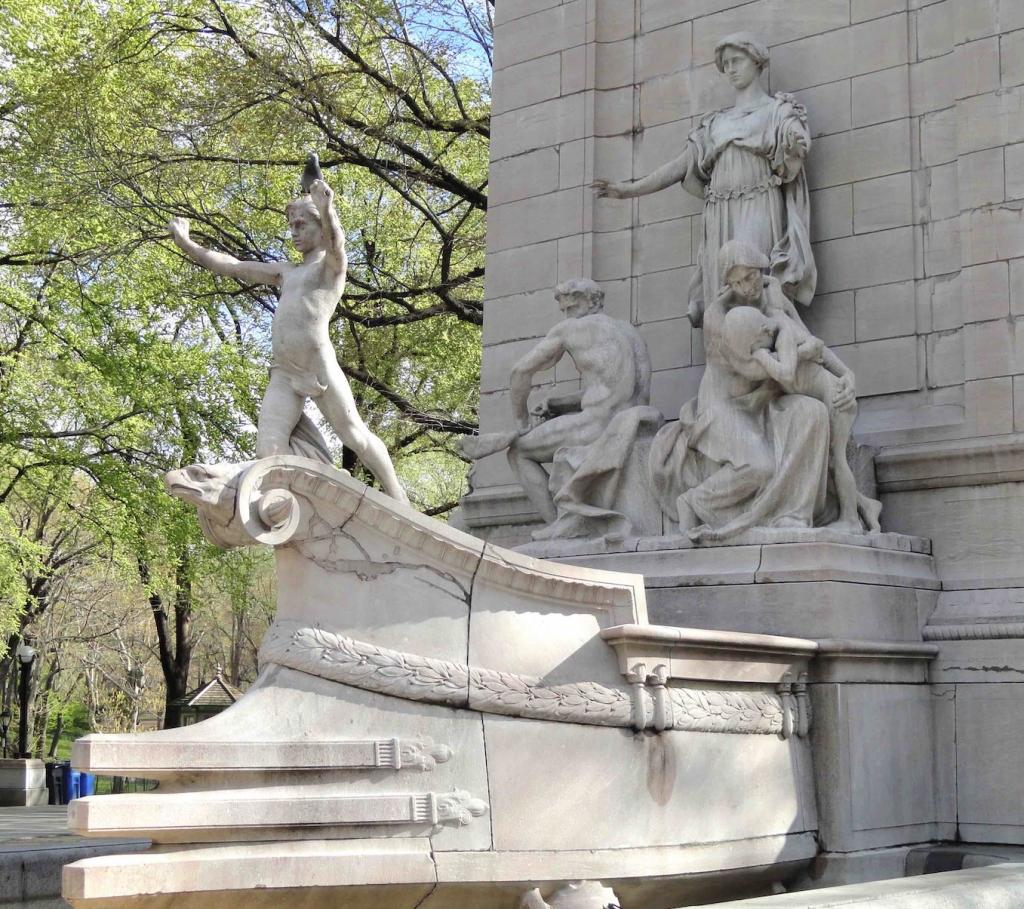

In the pivotal year of 1915, two crucial expositions celebrated the new Panama Canal, which was intended as the central artery of the emerging US dominions. San Francisco had its Panama–Pacific International Exposition, and San Diego held the Panama–California Exposition, and both attracted an unparalleled number of visitors to explore California. I have already mentioned San Diego’s imperial role, but we easily forget just how decisive an influence military and naval affairs had on the long term development of San Francisco, right up to quite recent times.

Both events left very substantial material structures that are vitally important to the cities today, but the religious consequences were incalculable. The San Francisco Exposition actively promoted New Thought as the religious vanguard of the new century. From about 1915, most of the New Thought leaders established institutions on the Pacific coast. George Wharton James declared of California as “the natural home of New Thought.” To quote Carey McWilliams, “these two imported movements – Theosophy and New Thought – constitute the stuff from which most of the later creeds and cults have been evolved… the mystical ingredients came from Point Loma; the practical money-mindedness from the New Thought leaders.” Other metaphysical movements boomed: just look at the imposing Christian Science churches we find across the West from these years.

That year 1915 marked the beginning of a national wave of interest in the occult and esoteric, and for the next couple of decades, every literary visitor to Southern California found themselves compelled to write shocking stories of cults and their naïve devotees. By the 1920s, those true believers created a whole new spiritual geography fitting to their location, with the growing belief that under the Pacific lay the lost continent of Mu, home to glorious ancient civilizations.

I have argued that 1915 can be understood in terms of its close parallels to 1968, when social crises resulted in a passionate hunger for new spiritualities. The term “New Age” is anachronistic in 1915, but it precisely catches the mood of that era, when broadly New Age and New Thought ideas penetrated so widely, including into some mainstream churches. That earlier spiritual world must be understood in the context of American empire and imperial expansion.

I offer a “mainstream” analogy here. At least from the late nineteenth century, many American Christian believers had high hopes of the seemingly limitless opportunities offered by missionary ventures in the Far East, and above all in China. Those hopes crested between the 1920s and 1940s, and then crashed with the Communist takeover in 1949. New Age and esoteric believers likewise looked out over the Pacific, and dreamed of idealized religious worlds. For both, westward the course of spiritual empire would assuredly take its way.

But it was not only the Pacific vision that promoted America’s first New Age. When the First World War created such general disenchantment with the claims of Western civilization, elites sought new hope in other old imperial borderlands, and in the nation’s oldest imperial subjects – namely, in Native Americans.

That sentiment originally emerged in the bohemian setting of Taos, where Mabel Dodge Luhan held sway, but it was soon popularized by very well known cultural figures like Carl Jung and D. H. Lawrence, and by well connected political figures like John Collier, who claimed to find among Native peoples a Red Atlantis. As Collier wrote, “The year 1919 saw the fading away of practically all that I, we, all of us, had put all our being into. My own disillusionment toward the Occidental ethos and genius as being the hope of the world was complete. . . . I knew that the old world was finished.” (This movement is discussed at length in my 2004 book Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality).

By the 1940s, Frank Waters integrated those Native ideas into a general New Age synthesis where they mixed and merged with Buddhist and esoteric thought, and that was the cultural package that had such an impact in the 1960s and 1970s. So many of the ideas and quirks that we associate with that era originated in the 1910s, and specifically in the context of mainstream White American encounters with empires and imperial subjects, both the oldest and the newest.

I will have more to say about these religious dimensions of American empire in several upcoming posts.