I have been preoccupied over the last few months by the subject of tradition in the Reformation—how it is constructed, where it is appropriated, and where the self-conscious breaks occur. As part of that preoccupation, I’ve turned numerous times to the question of transmission. How is the faith being passed on to the next generation when new beliefs and new ways of being Christian appear in the 16th century? One way this transmission happened frequently was in the writing and disseminating of new catechisms, manuals instructing parishioners in the basics of the Christian faith.

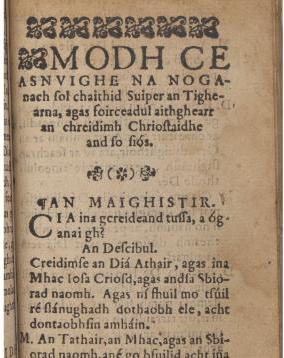

By all accounts, it would be quite fitting to call the sixteenth century, if not the age of catechesis, at least the age of the catechism. In the decades after Luther’s break with Rome, it seems that every churchman with at least a meagre education and a modicum of influence issued a program for pastoral education of the laity. Most of these catechisms shared a basic form centered around the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments along with some confessional statements about the sacraments. Many of them were in question-and-answer format, and within catechesis the subgenre of children’s education was quite popular.

Most catechisms were quite similar in their structure. But sometimes, much to the delight of sixteenth century readers and myself, the writers of catechisms would go “off script” as it were, often to indulge in some controversial theology, creative adaptation, confessional bugaboos, and a little bit of name-calling. The presence of polemic in these teaching manuals suggests to me that the catechetical genre could be quite flexible in scope and purpose. Rather than just giving instructions in the long-revered basics of the Creed, the Prayer, the Ten Commandments—church leaders could use these manuals to construct new religious borders, to chastise one’s neighbors or family members, or to insult one’s religious enemies.

In the past, confessional Protestant histories have been quick to emphasize that 1) post-Tridentine Catholic catechesis was especially polemical in its approach and 2) the great catechists of Protestantism largely avoided polemic in their works. This is true, as far as it goes. Luther’s 1528 Small Catechism was indeed more reserved in tone than some of his other, more salty treatises, while Robert Bellarmine’s famous catechism of 1597 was certainly polemical at many points. But the picture is more complicated.

The desire to “play nice” was not shared by all those who engaged in early attempts at Protestant catechesis, especially in places where the question of religious adherence was a live and contentious one. Today, I’ll illustrate this fact with three documents that arose in varying cultural and confessional contexts: Balthasar Hubmaier’s 1526 Anabaptist catechism, William Roye’s A Brefe Dialogue Between a Christian Father and His Stubborn Son of 1527, and John Carswell’s 1567 Scottish catechism found in his Foirm na n-Urrnuidheadh, a Gaelic translation of John Knox’s liturgy.

Three Pioneers of Religious Education

I’ll spare you the long version of how all three of these came to be. Suffice it to say, all three of these are historically important, although none of them had lasting influence in the movements they represent. Yet they all share characteristics that may prove helpful in looking at the function of polemic as a rhetorical device. First, all three are pioneering works in their respective territories of Moravia, England, and Scotland, being the first vernacular catechisms in print in each location. Second, all three employ a question-and-answer format and a focus on the education of youths. And third, all three draw on, yet significantly alter, preexisting catechetical source material. To further frame this exploration, I’ll note these works’ stated purpose and the varying points in the teaching when harsh rhetoric surfaces to see if there are any clues as to why such rhetoric was deemed useful in Christian education.

(One more note—someone may ask the question of whether all catechisms are inherently polemical. To this I answer, yes, all are by virtue of their exclusionary nature. But this does not mean that all catechesis uses the rhetorical device of polemic. The use of polemic as a device means that a text uses language self-consciously to attack, delegitimize, or suppress a literarily constructed “other,” to recognize the proximity of that other only to deny them a voice and dismiss their claims as self-evidently wrong. Here I’m drawing on Peter Matheson, Almut Suerbaum, George Southcombe and others.)

So let’s look at the stated purposes of these works first. On the face of it, the three catechisms are written to aid in the education of youths and to remediate the knowledge of the laity who had been failed by the clergy of the land. The prefatory material of each work serves as a springboard into later anticlerical language in each catechism.

Balthasar Hubmaier’s 1526 catechism is dedicated to Martin Göschl, erstwhile prior of the Kanitz monastery who settled in Nikolsburg, Moravia in 1526, shortly before Hubmaier arrived in the summer of that year. In his dedication, Hubmaier notes that it was Göschl who requested the catechism so that youths could be given pure doctrine that had for so long been “congealed in the mire and mud puddles of human precepts.” He writes that the church was plagued by “incompetent shepherds and pastors…whom we would in truth not have trusted to herd our pigs and goats, but still we had to accept them as our souls’ shepherds.” For Hubmaier, such men were not priests of the Mass but of Maoz, the foreign idol of Daniel 11:38 who must be honored with gold, silver, and precious stones. Hubmaier states that his catechism was written to provide “food and drink” for youths, to rectify his previous errors in doctrine, and to provide clear teaching of what one must know before receiving baptism into the “holy, universal Christian church.”

In the dedication of Roye’s Brief Dialogue, Roye states that he wanted to produce a text to aid the common person’s capacity which had been stifled under “great superstition which so long hath reigned and had the upper hand.” He was moved to do so because he thought it “most grievous to see the price of the precious blood of Christ so despitefully to be trodden under foot by such unclean swine”—that is, by the leading clergy of the Roman church. As Roye would have it, he stumbled on “a treatise most excellent” that was fitting for his cause. This, we now know, was Wolfgang Capito’s 1527 Kinderbericht, written in both German and Latin.

In the case of Carswell, no preface to the catechism is given, although the prefatory material for the Form provides hints as to the catechism’s role. In his dedication to the earl of Argyll, Carswell noted that “this testimony of Christ has been suppressed, and drowned, and polluted” by “the oppression of the Pope and other false apostles who have deceived the whole world…through great ignorance.” Thus, Carswell felt compelled as by God to “help the Christian brethren who have need of teaching and of comfort, and who have no books.” Like Roye, Carswell presented his work primarily as translation but, like Roye, Carswell took significant liberties with the Genevan shorter catechism, essentially creating an altogether new catechism based loosely on Calvin’s earlier work.

The prefatory material of the three works utilizes various, sometimes contradictory language to refer to Roman interference with true teaching; it could be simultaneously priestly ignorance and conspiratorial obfuscation; both the novelty of the medieval doctors and the blind obedience to ancient customs. In every case though, language of darkness and suppression appear. While this is significant, it is not in and of itself unique. After all, Luther’s small catechism was also prefaced by noting its necessity due to lack of teaching and lack of urgency among ministers and the laity. But the remedial purpose, paired with the catechisms’ shared status as texts situated on the front line of a burgeoning reform movement, suggests that defense against superstition and false teaching was an essential element in educating in the faith. They were not written with a long view in mind—catechesis for a reformed and socially stable church—but rather were created ad hoc for a decisive moment in time, a period of nascent religious pluralism in Europe, when the need was urgent and the stakes were high. We gain further insight into catechetical polemic by looking at individual questions and answers that focus on creating distance between the catechumen and the threatening religious “other.”

Teaching in the Trenches

All three catechisms use the pedagogical format of a question-answer dialogue to point sharp words at their traditional education, or lack thereof, in the Roman rite. The objects of their ire are not surprising—the Eucharist, images, baptism, veneration of the saints—but the language is at times shockingly pointed. The questions on the sacraments are particularly telling. For Hubmaier, infant baptism is nothing but a “bath” administered by those who are “water-priests.” Hubmaier’s constructed dialogue partners, Leonhard and Hans, also take up the question of the Mass. Leonhard asks, “what is the mass?” And Hans answers: “It is the very idol and abomination spoken of by the Prophet Daniel…By his honor he is recognized as the kind of God he is to the papists, maozites, mass-priests, sophists, and all belly-Christians.” Roye’s catechism addresses the question of why the doctrine of transubstantiation was not true, as the son in the catechism says, “as they whom men call ghostly fathers, doctors, and preachers do affirm?” The father answers that “they being blind would fain lead other blind with them into the pit of error.” Carswell notes that “they are directly opposed to each other, the mode of administering the sacrament according to Christ…and the mode followed in the popish mass.”

On the question of images, Roye notes that “maintainers of such abominable seductions” are “Baal’s priests” who “have no god saving their belly only.” So too Carswell, typically the most reserved of the three catechists, writes that “the erring priests stole away [the commandment against idols] from the Christian people, that they might place these lying images before the people as deceiving shadows in their own place, and so escape the performance of their own duty to the people, and besides from love to the gain they might obtain from the ignorant people in honor of these accursed images.”

Indeed, any clerical traditions that reinforce the traditional church hierarchy become the targets of Hubmaier, Roye, and Carswell. Hubmaier, drawing again on the apocalyptic imagery of Daniel, notes that the only true vow is the baptismal pledge that takes place in water baptism, a vow that has been lost for a thousand years. “Meanwhile,” Hubmaier writes, “Satan has forced his way in with his monastic vows and priestly vows and established them in the holy place.” Roye writes that such vows, like voluntary poverty, are taken by “belly beasts whom men call monks, friars, canons, nuns” who “promise they never will have thing in proper and yet in the meanwhile they devour up the blood and sweat of the other poor people.” On the question of following church tradition, Carswell writes that the command of God “was dimmed, or concealed, or corrupted very much in the time past, through the covetousness and ignorance of the priests.”

So what?

It’s clear from the brief scan over these three texts that anticlericalism and antifraternalism stand behind many of their authors’ choices. Why might polemic have been used in catechesis? I am hesitant to make any definitive statements based on three catechisms, and I recognize that the reasons are likely manifold and highly contextual. The varied social situations of even these three catechisms resist any imposed uniformity. So in lieu of any pronouncements, I have three hypotheses that are open to further testing.

-

Influence of the 16th century pamphlet wars on Reformation writing

In the case of both Roye and Hubmaier, we cannot discount the situation of the mid-to-late 1520s. Mark Edwards, Miriam Chrisman, Amy Nelson-Burnett, Andrew Pettegree and others have opened our eyes to the power of the pamphlet and its attendant rhetoric. Controversial literature was the demand of the day, the earthy language of the early Reformation as it took shape in the minds and mouths of the city and town. The abundance of pamphlets helped shape the opinions of the laity—but one wonders if they did not also shape the overall style and form of writing in the early sixteenth century. Was the literary atmosphere so saturated with polemic as to dampen the effectiveness of other written forms?

2. The social setting

It may be that many catechisms that utilize polemic share a similar social situation, as these three do. All three catechisms form part of a program of early literary penetration into a cultural vernacular. For Hubmaier, Roye, and Carswell, catechesis, for whatever reason, seemed a fitting mode for pressing the front line of a nascent ecclesiastical regime change. In such a context, the boundaries of community identity are reinforced not only by illustrating adherence to right belief but by self-consciously creating metaphysical distance where spatial distance is not yet possible. This is done by giving new believers conceptual tools to actively shape opponents (in this case, Catholic clergy) into objects of contempt, presumably through rote memorization. This may also help explain why polemic as a rhetorical device does not appear in catechisms like that of Geneva. For Calvin, his catechisms of 1538 and 1541 appeared as the fruit of a constitutionally ratified, city-administered reform movement already in process. He explicitly expresses a desire to avoid whatever is not basic and universal in Christian education, noting that catechists who are intent on “disseminating controversial matters in religion” profane baptism and fatally injure the church.

3. Fluidity of literary genre

The above points suggest that catechesis could be used not only for cross-generational transmission of the faith within the worshipping community but also for persuasion of potential converts. Ian Hazlett suggests this is the case with Carswell’s catechism: “The Strasbourg and Genevan catechisms were intentionally not overtly contentious, but Carswell’s introduces controversial elements and tones presupposing debate…An understanding of this gear change is that while Genevan non-polemical catechisms had existing Reformation communities primarily in mind, Carswell’s version also aimed to convert Catholics.” Eamon Duffy also points to the use of catechesis in English contexts as a tool of conversion, to “bring the tepid to a boil…to arouse to faith.” Indeed, this is suggested in the prefatory material of the three texts surveyed above. Such a purpose betrays the stated function of our three catechisms, the education of youths—or perhaps it expands what is meant by “youths” to include those who are young in belief, or those childishly holding on to irrational beliefs.

So were such catechisms written to create distance between the religious pure and their enemies, or to draw vacillating enemies into the fold of the faithful? Were they written to aid believing parents in the education of their children, or to convince doctrinally unstable parents on the prevailing questions of the day? Were they forms of interrogation or thinly veiled charges of apostasy? It may well be that authors of such works were so enraptured in the gravity of their respective moments, so consumed with zeal for the new faith, and so anxious in anticipation of the future, that they themselves were not interested in parsing out the distinctions assumed by such questions.

While lack of education of the laity had been a trope of church leaders’ complaints for centuries, it wasn’t until the Protestant Reformation ignited the ancient coals of what Nicholas Terpstra has called the obsession with purity, contagion, and purgation that church leaders began to put their minds and pens to the education of the laity in a concentrated way. Whether or not one utilized polemic likely depended on a complex interaction of variables, some of which I have at least pointed to—the literary ether and social location—but most of which I did not trace here, not least of which is the author’s personal disposition. But in cases where polemic was deployed and where it was not, pastoral concerns were at the forefront. In this way, polemical catechisms were true to their intention, even if they betrayed a certain level of elasticity in their presentation.