In recent years, American historians have reached a fair consensus that their nation’s history must be considered in terms of its being an empire, and from its earliest era. As such, we should apply to that history the insights of the modern study of empires, which is a very lively field of study. In this series of posts, I have been considering the implications for the specific theme of religion. Today I will be describing several critical aspects of that story, including such foundational matters as American attitudes to religious freedom, and the structure of its greatest churches and denominations.

In my recent book Kingdoms Of This World, I listed multiple factors common to empires in any time or place, which together constituted what I termed their “empire-ness.” These included, for instance, their construction of lengthy lines of communication, of new trade routes, of imperial cities, and the dispersal or migration of large populations. Empires mix population groups from previously unconnected parts of the world, and crucially, they spread common languages. All of these factors contributed to the spread of religions, which might or might not represent the approved creeds of the empire in question.

But empires vary enormously in how directly they seek to impose their rule, and to reproduce the conditions prevailing in their home society. As I discussed in my last post, some empires are happy to exploit conquered territories without settling large numbers of their own people. Others pursue a policy of settler colonialism, in which they largely or thoroughly replace older populations. That, of course, is what happened in the US context, and the religious consequences were sweeping.

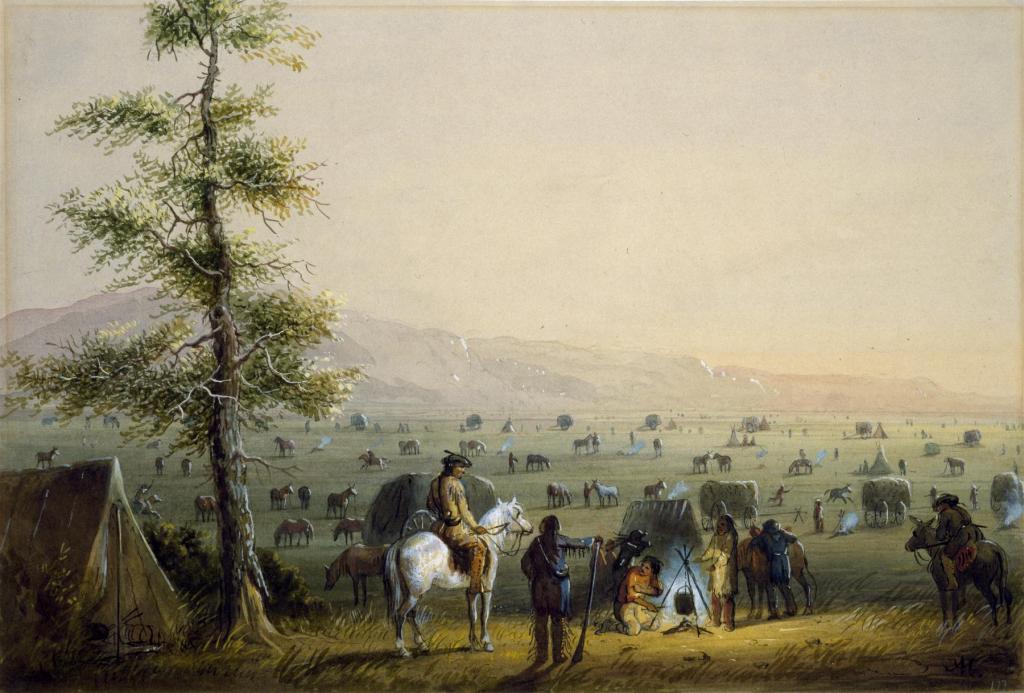

The comparisons might seem obvious, but they are illuminating. In much of the Americas, empires ruled over very large Native populations who retained much of their language and tradition, and European settlement was sporadic and gradual. In Mexico or Peru, religious life meant imposing new Christian forms in ways that accommodated and absorbed Native traditions – even on occasion to the point of facing charges of syncretism. In contrast, the settler colonial model meant thoroughly displacing Native traditions, and imposing thoroughly European concepts of Christianity. In practice, there was little need to accommodate to Native spiritual ways. As I noted last time, by 1930, the reported Native population of the US and Alaska was just 360,000, out of an overall national population of 123 million. If that was not Native extinction, it was close.

One of the great consequences of settler colonialism was not what happened, but what did not happen. In the British-derived world at least, American Christianity never had to consider issues of syncretism, or even religious accommodation.

Many imperial regimes used religion to justify their enterprises, and those ideologies strongly influenced the religious character of emerging societies. But in the case of the United States, with its settler-colonial patterns, religious ideas justified ideas of empire that were not just diverse, but were irreconcilable. In theory, Native evangelism and White settlement should have gone hand in hand, but in practice, this was close to impossible.

From earliest colonial times, British governments favored imperial colonies that, at least in theory, were obliged to spread the Christian faith among the Native peoples. Some colonists followed these directions faithfully, notably John Eliot in Massachusetts, whose settlements of “praying Indians” closely followed Spanish practice in their dominions. But most settlers also followed a deeply rooted Biblical tradition growing out of ancient Hebrew wars with Canaanites and other indigenous people, and according to this model, God’s Elect had an absolute duty to expel and eliminate the pagan inhabitants of the land. One variant of this story, targeted at the Amalekite people, seemed to demand not just the conquest of those rivals, but outright extirpation – that is, genocide.

The “Canaanite” or Amalekite model gained ever greater prominence during the quite frequent outbreaks of warfare between expanding settlers and older indigenous communities. That ideology provided the foundation for later theories of limitless imperial expansion, and Manifest Destiny. American churches thoroughly imbibed those ideas, and became some of their most enthusiastic advocates.

Religious policy provided a firm foundation for settler ambitions. In some empires, such as Russia, governments strongly directed settlement by Slavic and Christian groups. Settlement in the American colonies, and the United States after them, was highly voluntary for White residents (not, of course, for enslaved Africans), and governments had to tempt and encourage them. British North America incorporated multiple very diverse societies, each with its own distinctive religious order, in large part to encourage settlers from different British and European lands. From an early point, it became apparent that policies of broad religious toleration proved highly attractive in encouraging immigration and settlement, notably in Pennsylvania and, on a different scale, in Rhode Island. However sincere the intentions of the founders, such colonies knew that toleration was an excellent way to build wholly new European societies in the New World. Traditions of toleration and diversity continued to attract settlers and colonists through the nineteenth century, and each new group broadened the religious spectrum with its own imported forms. Religious freedom was an excellent foundation for imperial expansion.

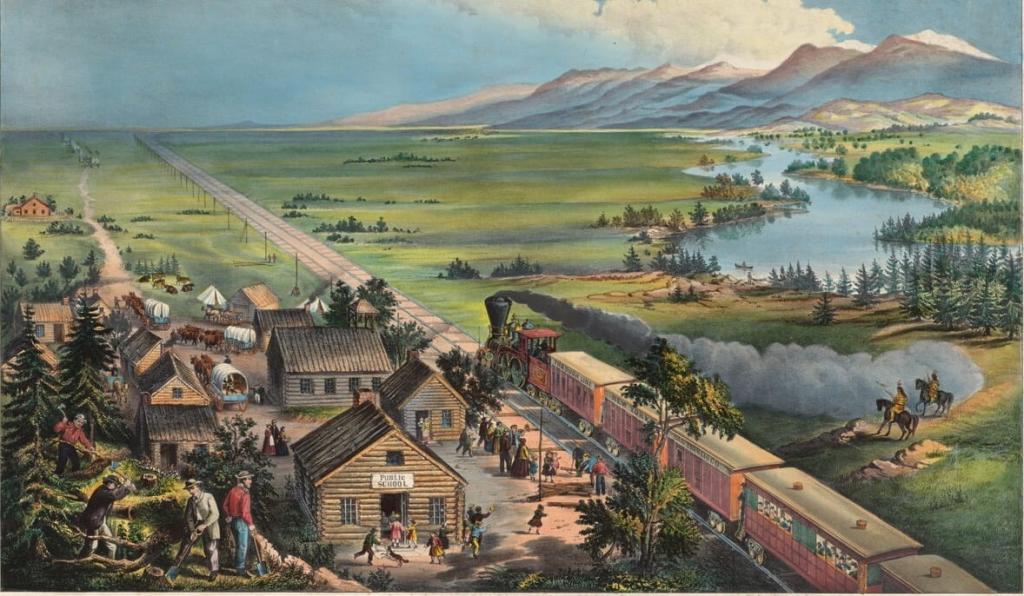

American imperial expansion, in its settler-colonial mode, not only spread new European-derived populations and cultures, but more precisely defined the religious structures they followed. As I have remarked, one critical aspect of “empire-ness” was the greatly expanded space on which institutions had to operate, far larger than anything contemplated in older European societies. Thinking as we often do that the growing US was in a sense just growing into its natural and predestined natural boundaries, we easily forget just how inconceivably vast was the territory it was acquiring during the nineteenth century. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 swelled the new country by over 800,000 square miles, an area ten times larger than the whole of Great Britain. In the 1840s, the US grew by an additional million square miles.

Such inconceivable growth had huge religious consequences, and especially for the older and more staid churches. In colonial New England, the most significant denominations tried to reproduce European conditions, with well-educated clergy assigned to particular areas. Among the largest was the Anglican/Episcopal church, which all but collapsed with the withdrawal of its (British) imperial sponsorship during the Revolution. Although the Congregationalists suffered no such political disaster, they could not hope to cope with the demand for new ministers as populations spread to the vast western lands.

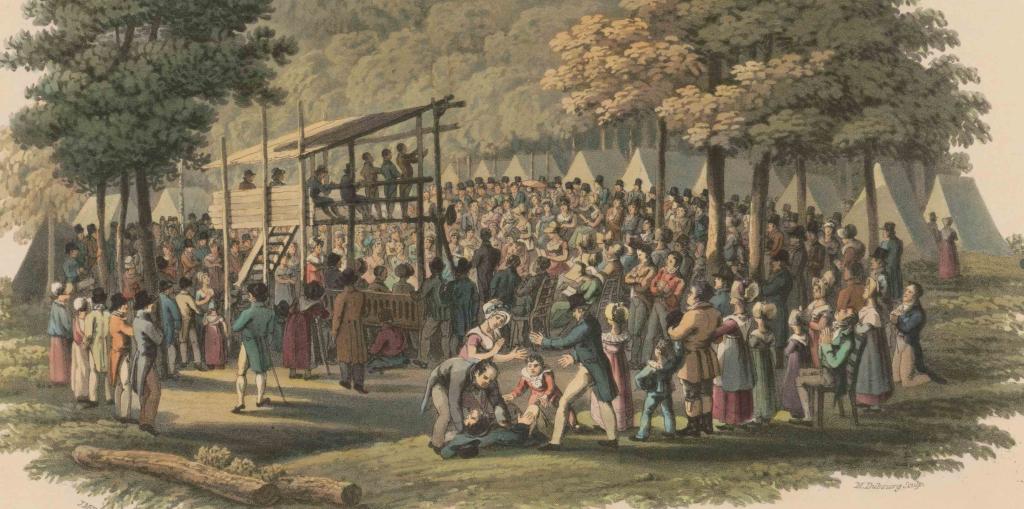

Between 1790 and 1860, the great story in US religion was the tremendous upsurge of the Baptists and Methodists, both of which were ideally suited to rapidly expanding settlement, with their decentralized and autonomous structures, and their lack of need for formally trained clergy. Highly mobile and flexible, these frontier faiths fitted perfectly in the expanding settlements. They also gained new vigor from the regular revivals along the advancing frontier of imperial settlement: the outburst in Kentucky in 1798 was one of the best known. Those movements in turn spawned new denominations, such as the Disciples of Christ.

American religion as we know it was born in space, and specifically the limitless spaces of the imperial frontier.

The Baptist and Methodist explosion had an enormous impact on Black American cultures. These churches were the first American denominations to permit Black congregations, with profound consequences for the long-term development of Black religious life, and for culture more broadly defined. Black churches, such as the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) showed early enthusiasm for the missionary ventures that were such a hallmark of imperial ideology, and had a special commitment to the American semi-colony of Liberia. Black churches sought to show their worthiness to participate in the imperial project. These stories too were part of the larger success of those churches, which were so well fitted for the new imperial worlds.

This is still very much a work in progress. I have a great deal more to say on these themes, especially the Catholic dimension, and oh my, those Mormons – the definitive religion of America’s advancing imperial frontier.

See also my full bibliography on American Empire here.