by Janine Giordano Drake

I think a lot about the Second Great Awakening. I think about its overlap with the market revolution, with the growth of Jacksonian democracy, with the rise indigenous removal and settler colonialism, and with the growth of Anti-Mormon and Anti-Catholic sentiment. But perhaps most of all, I think a lot about the role of the Second Great Awakening in forming Americans’ understandings of what a democracy looks like. Democracy, for so many Americans in the early nineteenth century, was put into practice through communal Bible studies, prayer meetings and musical worship, all of which were led by both lay people and ordained clergy alike. The class structure was alive and well in the early nineteenth century. There were people with lots of land and others who struggled to make ends meet as wage earners, people with disabilities, and people without work. Coverture was still an ordinary practice in most communities, and slavery was an expanding institution in the South. Americans were not equals under the law, in the voting booth, or in the home. Far from it. But, to so many Americans, “American democracy” meant joining on Sunday mornings as equals before the Lord. I often think about how Alexis deTocqeville should have given evangelicalism more credit for the marvelous “conditions of equality” he encountered in the burned-over-district of Western New York. I’m not the first person to make this observation and I surely won’t be the last. But to me, you cannot understand the” democracy” craze in the United States without understanding what it meant in the mid-nineteenth century to participate in an evangelical community.

The Second Great Awakening also helps me understand the social conflicts of the late nineteenth century. So many children of the Second Great Awakening in the Northeast empathized with abolitionists and other people of “conscience.” Many such believers supported the Underground Railroad, defied the Fugitive Slave Act, and opposed the wave of state laws and Constitutional amendments in the 1850s which excluded African Americans from land ownership and voting rights. After the Civil War, however, children and grandchildren of the Second Great Awakening took part in more intense disagreements about how to put the doctrines of human equality into practice. Some invested more in evangelism (in that classic Victorian sense of teaching “the Bible” to the “unreached”) than they did in interracial and cross-class worship. Others, meanwhile, believed they were carrying on the fundamental calling of their parents and grandparents by rejecting “brute capitalism” for its exploitation of fellow human beings. So many Americans in the late nineteenth century tried to carry on the “conscience” of their parents and grandparents in conceiving of new ways to run businesses and build communities. Late nineteenth century Christians cheered the expansion of both purchasing and productive “cooperatives.” These were not a brand new idea of course (see, for example, New Harmony and the many communities like it). Nonetheless, carrying on this older form of capitalist production in a rapidly “industrializing” country was making a statement about the real possibility of a business-without-exploitation in a modern United States.

I often tell people that the elections of 1912 (for presidential, state and local offices) served as a referendum on the next big “Strategic Plan” for American evangelicals. For many grandchildren of the Second Great Awakening, the answer was clear: socialism needed to replace capitalism as an organizing principle for most commercial activities. Socialists wanted utilities (water systems, transportation systems, electricity systems, and communications) to be owned and managed by communities. They appreciated independent proprietors (what we call “small business”) but they loved community cooperatives like granaries and cooperative groceries, which directed the profits of the “economies of scale” back into the community. Socialists opposed monopolies and trusts,

what they called the “conglomeration of capital,” for the way it strangled out both small business and the opportunity of hard-working farmers and independent proprietors to support themselves and their families.

And yet, around 1912, for other grandchildren of the Second Great Awakening, “capitalism” did not feel like such a problem. Much to the contrary, capitalism felt like the key to all the social mobility their family had experienced over the previous two generations. As early twentieth century evangelical Republicans told the story, non-Protestant immigrants and their radical ideas about politics, religion, and culture were eroding the “democratic values” the nation had long held dear. To name one example, the conservative response to the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike–a strike led by Italian American women and the IWW–was a “patriotic parade” with large replicas of Uncle Sam swinging around the American flag. Conservative Protestants of the early twentieth century reminded one another that American jobs were a gateway to opportunity. They thought that their own hard had flowered into all the material comforts of the modern age.

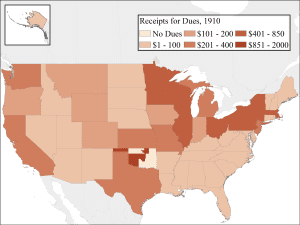

When Americans debated socialism and the next steps for Christians in the early twentieth century, they were really fighting over how to memorialize the Second Great Awakening. I see this debate, for example, in this map of the Dues Paying Members of the Socialist Party in 1910 (which we made based on data from a Socialist Party Yearbook). We could superimpose this map on a map of the Methodist circuits of the 1840s or the Underground Railroad and see substantial overlap. We could also superimpose it on a map of the many “cooperative settlements” of anti-capitalist (so called utopian) Christian socialists in the mid nineteenth century. So many of the American socialists of the early twentieth century saw themselves bringing their parents’ vision of a Christian democracy into its modern form.

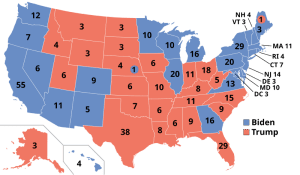

It is interesting to reflect on the ways that so many of the “battleground states” for the presidential elections of of 2020 and 2024 were also the site of the culture wars of the 1910s. We’re still debating the relationship between Christianity and democracy

in Western New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Illinois. In so many ways, we are still fighting over how to define Christianity for the American democracy, and how to put that vision into practice.