Empires are a very hot issue in historical scholarship right now, and missions and missionaries are an important part of the subject. That goes far beyond a crude stereotype of the missionary as a cynical servant of empire, preparing the way for conquest and exploitation. The relationship between missions and empire is complex, and especially so in an American context. That is one theme I am discussing right how in the book I am presently writing on Religion and American Empire. I want to illustrate this in the context of one particular part of American informal empire or quasi-empire, namely that in the Middle East.

American Missionaries and Empire

The United States was an early and passionate sender of missions, dating from the establishment of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1810. American missionaries were son operating across the globe. In terms of American political power, these figures occupied a special place because of the expertise they acquired in remote lands – in languages, in social customs, and the political situation. This was uniquely important in a US context because Americans did not have the long history that European powers shared of commercial enterprises and great corporations like the British and Dutch East India Companies. American governments often relied on missionaries to consult on particular situations, to serve as diplomats, consultants and spies. They were so important that missionaries often led the way in policy making, sometimes drawing US governments into situations where they were far from comfortable.

That importance went beyond the first generation of actual missionaries in the field. Over time, families with missionary backgrounds inevitably acquired a far more international outlook than neighbors who might be wealthier and in other ways better educated, so that new generations naturally gravitated to careers in international commerce, or (commonly) in diplomacy or intelligence. Here, their languages and intercultural skills served them very well indeed. Interacting with other similar families, they formed whole missionary and post-missionary dynasties, who cast their influence over generations. Those families continued the work of building and defending American empire.

Obviously, I am drawing here on the work of several very active current scholars, including Emily Conroy-Krutz, Daniel Bays, Dana Robert, and Matthew Avery Sutton. I think I am the first to use the term “post-missionary” in this sense and context: I find it to be a very useful concept.

The American Middle East

In writing the history of empires, various key dates suggest themselves for their beginning, peak and end. One that rarely receives the attention it deserves is 1911, which was the year that the British Royal Navy (under the guidance of Winston Churchill) decided to shift from coal to oil as its main source of power for its ships. All the world’s navies soon adopted the policy, which made it so crucial for any Great Power or empire to secure reliable sources of petroleum. The easiest and most obvious were in the Middle East, where the British and French had interests dating back several centuries, and where the Germans, Russians, and Italians were soon hoping to create their own areas of influence or outright dominance.

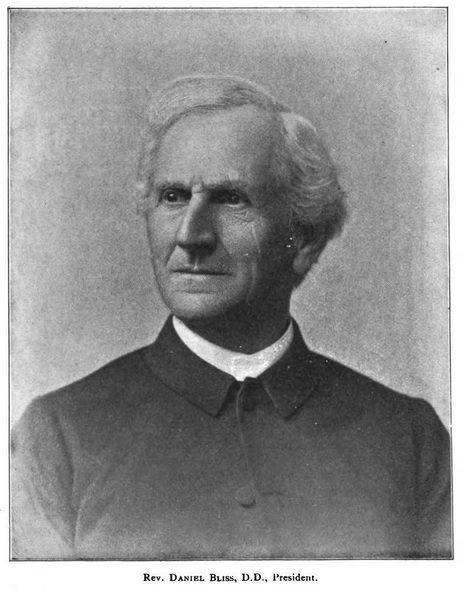

As so often elsewhere in the world, the Americans did not have such ancient and complex records of political and military interaction with the Ottoman world. What they did have was missionaries, who from the earliest periods of American enterprise had focused on the Middle East. In 1862, the ABCFM decided to create a Syrian Protestant College, to be headed by Dr. Daniel Bliss. This opened in 1866, and subsequently in 1920 changed its name to the American University in Beirut, AUB. In 1863, Robert College was created in Constantinople: it is now the oldest continuously operating American school outside the United States.

The strong American presence in the Middle East was vitally important in the two waves of the Armenian Genocide, in the 1890s and in 1915. Missionaries carried news of the horrors to the international community, pleaded for intervention, and in short helped direct US poicy towards gigantic humanitarian efforts of the kind that we are so familiar with in the modern world.

Oil, Empire, and Influence

So what does this have to do with oil or empire, and more specifically to informal empire? Partly, it is a matter of cultural empire, of soft power. Both AUB and Robert College educated generations of Middle Eastern political and cultural leaders, to the point that they are indispensable to any account of the modern history of the Middle East, or of the Arab world. Certainly, such colleges did not create any sweeping expansion of Christian faith in the region, and plenty of their graduates became celebrated for nationalist, radical, and anti-Western attitudes. (The Ba’ath Party that so long ruled Iraq and Syria traces its origins to AUB alumni). But the deep expertise in the region acquired by the American missionaries, and their extensive connections, gave them a potent role in foreign policy discussions, in a region historically dominated by British, French, and other European interests.

The key names were the Bliss and Dodge families. These began their missionary ventures in the Middle East in the 1860s, and they deep roots acquired vast new significance with the crucial significance of oil resources in the early twentieth century. The Dodges had a very strong political presence in the US, arising from the immense wealth arising from the Phelps Dodge mining corporation. That firm represented an earlier stage of imperial expansion, with its massive interests in the borderlands in the southwest, in Arizona and New Mexico, and later generations of the family projected American power to new parts of the world. Industrialist Cleveland Dodge was a critical financier for the election of President Woodrow Wilson, and during Wilson’s administration Dodge was the most important single individual in shaping US diplomacy in the Middle East.

Successive generations of Dodges were heavily involved in the exploitation of Middle Eastern oil by American corporations, besides the family’s related ventures in diplomacy and intelligence. Even so, they never lost their ties to missionary and educational enterprises: as late as the 1990s, David S. Dodge served as president of AUB.

Missionaries and Spooks

Also active in the creation of AUB were the Eddy family, another multi-generational line of Presbyterian missionaries. In later years, the family was represented by William A. Eddy, who was born in what we would today call Lebanon, and who acquired excellent Arabic. His distinguished military and diplomatic career included time as a leading intelligence agent in Morocco in the Second World War, when he was deeply involved in quite bloody active measures against German and Axis forces. From 1943 through 1945, he served as US Minister to Saudi Arabia, and was pivotal to shaping the US relationship to that country, and its oil industry.

Eddy was among the principal founders of the post-war CIA. His colleagues in that enterprise included Stephen Penrose who likewise came from a distinguished church family and later served as President of AUB. During the war years, he supervised American intelligence efforts in Egypt and the Levant (See Matthew Avery Sutton, Double Crossed: The Missionaries Who Spied For The United States During The Second World War, 2019).

When we write the history of US informal empire in the region, as manifested especially in the history of the great oil companies, time and again we come across such missionary and post-missionary backgrounds.

This was not just a Middle Eastern story. Witness the Dulles family. John Welsh Dulles was a Presbyterian minister who began his missionary career in India in 1848. His wife was the daughter of pioneering American missionaries in Sri Lanka, where her mother Harriet Winslow had founded the first all-girls boarding school in Asia. After returning to the US, John remained committed to missions until his death in 1887. His son followed him in the Presbyterian ministry, and he in turn became the father of two crucial figures in the mid-century US, namely Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and Allen Welsh Dulles, the first civilian director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

With that family background, it is less than astonishing that they saw their task, their mission, in religious and even millenarian terms, stressing America’s special divine mission in the Cold War confrontation. At the height of the Cold War in the 1950s, both Dulles brothers acquired global notoriety among leftists for what was portrayed as their ruthless enforcement of perceived American interests, often through cover action, subversion, and violence.

The Missionary-Petroleum Complex

I have used the term informal empire or quasi-empire, which I have earlier discussed in the context of the Caribbean and Central America. A Great Power dominates a region, even if that region is never a formal possession, and there is always the veiled suggestion that military intervention might happen if a lesser power gets out of hand. The US situation in the Middle East was somewhat more complex, especially given the rivalry with other overtly imperial states, Britain and France. Nor was the Saudi Arabia under the house of Saud any kind of puppet: managing the state required careful diplomacy, by skilled and sensitive intermediaries. This was a delicate relationship.

But for much of the twentieth century, it was Saudi oil that was so critical to the US world system. When that position was challenged, as during the oil crisis in 1973-74, the US drew up serious plans to seize Saudi oil and occupy the country. When the country was again challenged by Iraqi aggression in the early 1990s, the US sent in sizable military forces. That had the unintentional effect of sparking the growth of al-Qaeda, whose leaders were so appalled by the presence of infidel boots on Arabian holy ground. But the odds were too high. I would argue that the language of informal empire applies totally to this Saudi situation, at least before 1973, and probably for long afterwards.

Missions, oil, empire, and intelligence were inextricably linked.