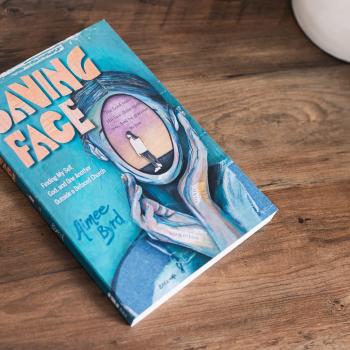

The 1991 Christmas standard “Mary Did You Know” was an oft-repeated anthem for many of us over past Christmas seasons. With its repeated titular question, the song is one of a relative few modern songs to focus on the perspective of Mary in the Christmas story. Its emphasis, however, is characteristically Protestant: not on Mary as the mother of God or as a key part of the Christmas story, but on Mary as a figure observing the Christmas story unfolding without an understanding of the significance of what she is seeing.

In the Middle Ages, Mary was a far more popular dialogue partner in Christmas and devotional texts. Importantly, she was not just a spectator to the Christmas story, but a figure providing insight into God’s plan, into what unfolded over the Advent season, and into the nature of God more generally. Medieval mystics like Marie of Oignies or Margreth Flastrerin, both discussed in Mary Dzon’s and Theresa Kenney’s work The Christ Child in Medieval Culture, envisioned themselves as Mary, actively engaged in the Christmas story and in the childhood of Christ. Yet, because many of these texts are framed around Mary herself– in Marian odes or prayers or hagiographies– modern evangelical audiences tend to overlook them. What might these Marian odes have to say to us during the Advent season?

One such ode comes from the 9th century author Hrosvitha (c. 935-1000). Hrosvitha was a woman from the area known in our modern era as Germany. She was born to a noble and wealthy family but spent most of her life as a nun in a Benedictine convent. She wrote six comedies in Latin that embodied Christian themes as well as other narrative poems and verse chronicles. Through her writings, she sought to provide education and spiritual edification for her fellow nuns and to strengthen their understanding of Christian virtues and theology. Her name means “mighty voice,” perhaps a reference to the power of her written works, the first surviving poetic and dramatic works from a German woman and the first dramas written in the Latin West since the collapse of the Roman Empire.

One of her writings is a text called the Maria, a saint’s life of sorts focused on the Virgin Mary. Drawing on the apocryphal text the gospel of James, Hrosvitha’s Maria begins with her miraculous conception and birth before proceeding through her pious childhood, her marriage to Joseph, the angel’s announcement to Mary about her role in the Incarnation, and then the birth and early years of Christ.

Parts of this Marian ode lay out beautiful reflections on the Incarnation. For example, in the description of the birth of the Christ child, Hrosvitha describes the scene as follows:

“Here in the calm midnight hour the Virgin Mother in joy brought forth her divine Child, venerated throughout all ages, Jesus, to Whom be praise, glory, and power; Who coming to fulfil the predictions of the ancient prophets, fortelling that He was to come into the world for our salvation, established peace between the heavenly citizens and the terrestrial. As soon as the Blessed Virgin, all chaste, had brought forth her Child, there appeared a throng of heavenly citizens praising in subdued tones the Maker of the universe, celebrating the Child sent for us from the stars. But presently venerable Mother Mary wrapped the tender limbs of Christ, the Eternal King, in swaddling clothes and laid Him in a narrow manger.” (Hrotsvitha, “The Maria,” in The Non-Dramatic Works of Hrosvitha : Text, Translation, and Commentary, Translated and edited by Gonsalva Wiegand. (PhD Dissertation: Saint Louis University, 1936; p. 47)

Mary’s reactions to the events leading up to this point– to the annunciation, to the call for a census, and the trip to Bethlehem– are not those of someone surprised by the fulfillment of God’s plan, but of a knowing and willing participant in the fulfillment of promises and prophecies. She didn’t need the angels around the manger to know that the child born that night was part of something much bigger.

Earlier in the text, Hrosvitha even points to Mary’s birth and childhood as part of this revealed knowledge of God’s plan of salvation, as Mary is the first signal that the promises of old were being fulfilled. In talking about Mary’s own birth, Hrosvitha notes that even at this time, before the Annunciation and Incarnation, God’s Light was coming into the darkness:

“And thus gradually the glory of the Heavenly Father began to break forth to the world in resplendent rays, and ancient discord was brought to a definite end as soon as the celestial citizens had promised companionship with themselves to those earthborn citizens whom hitherto they had disdained by reason of the guilt of their Father, Adam. Neither did the clemency of the All-Father lie hid from the angelic host when in the fullness of time, He in His mercy decreed to send his own Son into the womb of a Virgin, in order that this Son, born of the Father before all ages, might in time assume flesh of a Virgin Mother, and thus save all mankind by His all-holy Blood, and that after this the wily enemy of man might not rejoice in holding the world in his malicious snare; but that the Godhead of the Father and of the Son and likewise of the Fostering Spirit, equal in nature, might under this triune Name, reign as is just throughout the peaceful world even unto the end of time . . .” (Hrosvitha, “The Maria,” pp. 25-27)

In pointing to Mary as not just a passive observer of the Christmas story, but as an integral part of the coming of the light of God into darkness, Hrosvitha is able to point us as readers to the fuller theological truths contained within the Nativity, including the guilt of humanity, the salvation promised through the Incarnation, and the eventual triumphant reign of the triune God over all.

In response, both Mary (and Hrosvitha and her readers) are called to two things: to recognize and know the God revealed through the manger, and to worship this triune and gracious God through praise and action. The Maria concludes with several episodes where a young Christ teaches his parents about His father and points them towards hope, not fear. In response, Hrosvitha herself breaks out into an ode not to Mary, but to Christ:

“O how praiseworthy is the grandeur of your power, O Christ! . . . You, born from the Father before all ages, did in obedience to His Will take up your abode in the womb of your mother and did take from her a human form in the fullness of time; You are able to enclose the world in the palm of your hand but did not despise to be wrapped in swaddling clothes of little worth; You, whose throne is above the starry skies, did become small enough to lie cradled in a tiny manger; You who did name the myriad constellations and are able rightly to count the drops of rain and the grains of sand on the seashore, did as a helpless babe abide in patience silence while you did dutifully take nourishment from your Virgin-Mother’s breast . . . Therefore to Your Eternal Father may glory be throughout all ages from your creatures, Who knew not how to spare His beloved Son; and likewise to You, Christ, be eternal honor, victory, and power. Who did shed Your Blood to redeem the world on its way to perdition; together with the Holy Spirit, be glory throughout all ages, through Whom all heavenly gifts are granted to us! What gifts shall I render now to the Creator, worthy of all the good He hath bestowed upon me, Who graciously in His wonted goodness hath permitted me, an unworthy servant, to render thanks, however feeble? For this, may the angelic hosts, I pray, unceasingly praise the Lord.” (Hrosvitha, “The Maria,” pp. 63-65)

Hrosvitha’s active and knowledgeable Mary ultimately responds to the events of the Nativity not through passivity or through blind holiness, as in so many modern representations, but instead through learning about God, through teaching others about Him, and then through active praise and good works. In doing so, she provides a model for all of us as we encounter the deep theological truths of the Christmas story.

The popular 1990s anthem “Mary, Did You Know?” tries to express some of these same marvels of the Incarnation, but ultimately, does not provide us with a way to respond. We are observers in the story rather than participants, men and women alike (but perhaps especially women, at least within the framework advanced by much of popular evangelical culture). The medieval Mary, at least according to authors like Hrosvitha, knew– she was no passive woman simply watching God’s plan unfold, but an active participant in it. Because this medieval Mary knew, increasingly so as her relationship with the Christ child increased, she provides us with a model of Christian action and worship in response to the wonders of the Incarnation that we are called to reflect upon during this season of Advent.