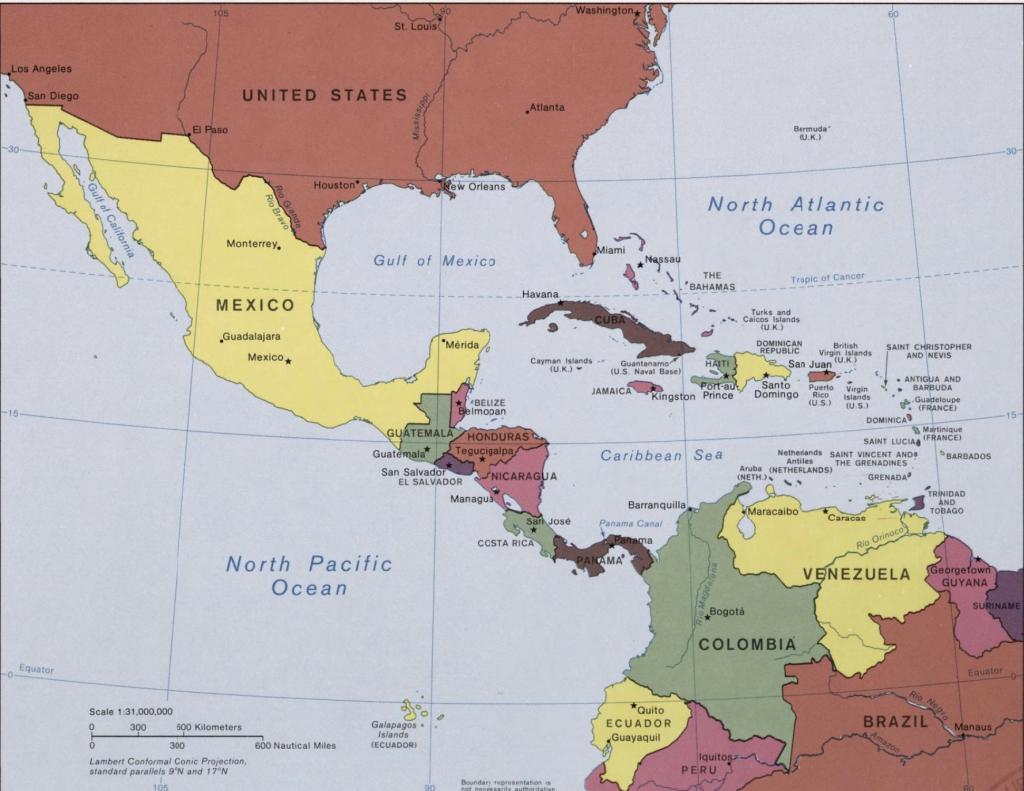

During the 1980s, Central America was the setting for brutal revolutions and civil wars that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. The United States was closely involved in all these struggles, and I have argued that they must be seen in the long-term context of American empire and quasi-empire: they were America’s Late Imperial Wars. As in another such contexts through imperial history, such wars had profound consequences for the homeland. To adapt a famous phrase, what happens on the imperial frontiers does not stay on the imperial frontiers.

The long wars had a deep and lasting impact on American religious life, one that bears many parallels to the much better-known divisions of the Vietnam era. Far from being a mere adjunct to secular protest movements, clergy and religious groupings became quite central to the very lively opposition culture. Religious wars, political struggles, and culture wars were inextricably linked – although this 1980s crisis is now largely forgotten, or at least underplayed. Some of the practical results live with us today, in terms of debates over immigration, which are going to be ever more in the headlines in the next few years.

Imperial and post-imperial battles overseas generated a religious struggle within the United States.

Fire in the “Backyard”

Just to summarize the background briefly, revolutions and discontent were simmering trough the region from the 1970s onwards, leading to a successful left-wing revolution in Nicaragua in 1979, under the Sandinistas, and there were keen hopes and fears of a similar outcome in El Salvador and Guatemala. Although these movements undoubtedly had strong local foundations, they were just as clearly supported by Cuba, which was a proxy for Soviet influence in a global Cold War which was then at its height. The US armed and sponsored counter-revolutionary forces in each country – repressive regimes in Guatemala and El Salvador, and insurgent guerrilla armies in Nicaragua, the so-called Contras. In their ideal world, the Reagan administration would have considered an invasion of Nicaragua, but that was politically impossible.

Crusade in Central America?

If you were a regular mainstream American Christian following the religious press or media during these years, you were very closely attuned to the crisis, due in part to the long history of missions and missionaries on the imperial frontier. Protestant and Pentecostal missionaries had scored major victories in recent years, leading to hopes that the whole region might experience a New Reformation. Intimately linked to these visions were the apocalyptic and end-times concerns of the era, with their intense focus on Soviet Communism. If you watched the evangelical religious broadcasters of the era, notably The 700 Club, which was then at its viewing peak, they vigorously sounded the alarms about Communist expansion. Specifically, the program campaigned constantly for the US to support the Contra forces. This was a vital issue at the time: the Reagan administration made funding and arming the Contras a centerpiece of its Cold War policies, but it could rarely convince a Democratic-dominated Congress to go along. This became all the more difficult, and controversial, following major Democratic gains in the 1982 mid-terms. Televangelists became primary vehicles for making the administration’s case.

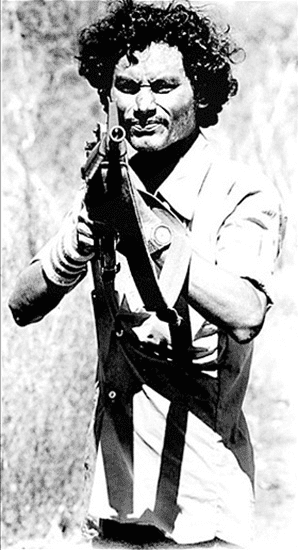

The program hero-worshiped Guatemala’s dictator, Rios Montt. I quote Counterpunch:

[Pat] Robertson took a personal interest in the strife torn Central American nation, developing warm ties to General Efrain Rios Montt, a born-again evangelical Christian. When Rios Montt took power in a military coup d’etat in March of 1982, Robertson immediately flew to Guatemala, meeting with the incoming president a scant five days after he came to power. Later, Robertson aired an interview with Rios Montt on “The 700 Club” and extolled the new military government.

Rios Montt was, basically, a monster, whose forces were then engaged in the mass slaughter of the country’s overwhelmingly Catholic Indian peoples. As I have suggested, this was a religious war as much as an ethnic or political conflict.

Jerry Falwell was equally devoted to the cause. Robertson, meanwhile, had Presidential ambitions, and he ran an active campaign in 1988. The televangelist Right made a national hero of Oliver North, who directed covert illegal efforts to fund the Contras.

Evangelicals as such did not act as a bloc in such matters, but a great many certainly favored the Reagan-Falwell approach, especially in matters of Contra funding.

Martyrs and Protesters

Other American Christians held a diametrically opposite view, in which opposition to US policy in El Salvador and Nicaragua became something like an act of faith. Again, this was partly due to the long record of missions in the region, which had given a good number of Americans direct experience. Also, it was difficult for such observers not to have had at least some awareness of the liberation theology that was then so very influential across Latin America. Liberation-minded Catholic clergy strongly favored the Sandinista regime, which included some radical priests in its leadership. Priests, religious, teachers, and church workers made home parishes aware of such trends, which were duly reported in church news media.

This reinforces the message of the excellent recent book on Missionary Diplomacy by Emily Conroy-Krutz. Empires sponsor missions, or at least make their activities possible, and missionaries acquire skills, together with direct knowledge on the ground, that often set them far above secular professionals. They thus become invaluable to empires, but they can lead policies in directions the empires do not favor – provoking acts of aggression and conquest, emphasizing concerns over religious freedom and humanitarian crises, or, as in this case, driving anti-imperial activism. Moreover, the reports they bring back home, the missionary intelligence, have an amazing capacity to reach ordinary believers in their congregations.

In the Central American case, those church workers were closely rooted in local communities, they were well informed about official violence and misdeeds. Two episodes in El Salvador in 1980 acutely focused such outrage, namely the murder of four US churchwomen, and the murder of that country’s archbishop Oscar Romero. Each incident in its way was widely reported as an egregious example of modern-day martyrdom. Increasingly, many American Catholics strongly identified with the leftist movements in the region, and became among the most vocal critics of US policies.

If you want to get a sense of how left and liberal Catholics interpreted these issues, turn to two bestsellers by Penny Lernoux, namely Cry Of The People: United States Involvement In The Rise Of Fascism, Torture, And Murder And The Persecution Of The Catholic Church In Latin America (Doubleday, 1980); and her People Of God: The Struggle For World Catholicism (Viking, 1989). Or really, any issue of National Catholic Reporter from the era, where Lernoux was also well represented.

Or, you might watch the remarkably good Oliver Stone film Salvador (1986), with James Woods. This harrowingly depicts the two key events of the murder of the church workers, and the Romero assassination. Other films of the era sent a similar message. The 1983 Nick Nolte film Under Fire had already offered a very sympathetic portrait of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua. In 1989, Romero was in effect a hagiography of the murdered archbishop.

We should recall the political splits in the US Catholic church at this time, the two decades or so after the Second Vatican Council that have aptly been described as the “Catholic civil war.” See Kenneth Briggs’s study Holy Siege: The Year that Shook Catholic America (Harper 1992): this focuses on the year 1986-1987, but most of the remarks apply much more widely through the period. Briefly, conservatives and the hierarchy were ranged against insurgent clergy and laity, over such issues as clerical marriage and celibacy, women’s ordination, and such secular matters as nuclear weapons.

Naturally the radicals and liberals were passionately concerned about the Central American crisis, but many conservatives likewise were appalled by the murders of clergy and church workers. Even strikingly conservative bishops made it clear that they were not going to support US aid to the Salvadoran regime that had perpetrated or tolerated such atrocities. However oddly they might have viewed the fact, those conservatives actively found themselves on the side on secular leftists and liberals who were equally shocked by the situation, and who loudly warned of a new Vietnam in Central America. As the slogan declared “El Salvador is Spanish for Vietnam.” Catholic outrage over El Salvador spilled naturally into anger at Contra funding.

Through the 1980s, domestic American protests about Central America and the Contras were highly likely to be led and mobilized by Catholics, including clergy.

Pro tip: If you want to track the secular leftist/liberal views of the 1970s and 1980s on pretty much any issue, in highly accessible form, you can do a lot worse than to follow the coverage in Doonesbury, which was highly attuned to the news, and was always well informed. The writer, Garry Trudeau, is married to Jane Pauley, for heaven’s sake. Trudeau offered much coverage of the Central America issue. In one item I like, an American spy is scoping out territory for the likely imminent invasion, as bemused locals ask why he is so interested in the place they call the Bay of Piglets? The suggestion is that such a US move would end in catastrophe, as had occurred earlier in Cuba. Trudeau also regularly featured the activities of Rev. Scot Sloan, a fictional radical cleric deeply involved in protest movements. I could easily choose many similar examples.

Migrants and Sanctuary

In my last post, I described the sweeping refugee movements caused by the Central American wars and persecutions, and how migrants contributed to building new churches both in the region, and in the United States. As so often, we see a continuing process of interplay and feedback, which has left such a mark on so many congregations within the US itself. But that migration also had other far-reaching consequences.

As Central America came to be so prominent in public debate in the early 1980s, attention focused to the many displaced people from those parts who sought to migrate to the United States. Between 1980 and 1991, around half a million Central Americans took this route, although in the great majority of cases, those migrations were illegal. Religious activists, drawn both from Protestant mainline churches and Catholic activists, sought to assist the people concerned to evade controls. These campaigns explicitly drew on religious language and rhetoric, so that the interfaith groups pledged to resist immigration laws coalesced under the title of the Sanctuary movement. Some five hundred churches were involved, from across the denominational spectrum. (Doonesbury‘s fictional Rev Scot was a very active member, leading undocumented migrants to safety)

Liberals and progressives borrowed the sanctuary terminology to argue for laws that limited the ability of law enforcement agencies to inquire into the immigration status of individuals. San Francisco passed the first such measure in 1985, and it was widely copied. Such communities proclaimed themselves Sanctuary Cities, or Cities of Refuge (an Old Testament term more congenial to Jews). In 1986, the US government prosecuted some key activists, who in their defense cited the principles of civil disobedience, and harked back to the Underground Railroad. They also quoted Biblical verses such as Leviticus 19:34 and Isaiah 14:32.

The Sanctuary movement has been very significant in shaping the flow of migrants to cities, and establishing the idea of non-cooperation with federal officials, which has been such a controversial part of current immigration debates. With mass deportations at least a prospect in coming months, the principles of Sanctuary will undoubtedly be heard once again. (There is by the way a sizable scholarly literature in the Sanctuary movement, Sanctuary jurisdictions, and the whole legal debate they inspire).

The ghosts of the 1980s might yet be among us again.

I have already mentioned some cinematic treatments of the crisis and its impact. Other very well-regarded contributions include El Norte (1983) about two Guatemalan refugees to the US. The 2019 film La Llorona is a treasure, a supernatural folk-horror film based on the same Guatemalan massacres of the 1980s, and the supernatural revenge against the military perpetrators.