Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on The Spirituality of Children. Read other perspectives here.

"You guys do know that you're in the Danger Zone, right?"

I could see those with wandering attentions in my audience zoom right back in.

"You are all in the age range at greatest risk of starting to become 'rather stupider,' like Curdie did." The entire Gr 6 – Gr 12 group was now fully attentive. Who wants to succumb in the Danger Zone and become "stupider"??

Moments earlier I had read to them one of my favorite passages in literature:

As Curdie grew, he grew at this time faster in body than in mind — with the usual consequence, that he was getting rather stupid — one of the chief signs of which was that he believed less and less in things he had never seen. […] He took less and less notice of bees and butterflies, moths and dragonflies, the flowers and the brooks and the clouds. He was gradually changing into a commonplace man.

The need to maintain, to cling to (and try to never let go of) childlike delight — childlikeness itself — is rarely considered these days. We are so busy preparing children for the "adult world" that we usher (push) out of them the very state that will help them to deal with and carry on through Life. Mistaking childlikeness for childishness, we "grow them up" — unaware of how doing so may actually impede healthy maturation. Often those adults most interested in the spiritual welfare of their children are the quickest to push.

My husband and I have a lot of children in and out of our home — children from a wide variety of backgrounds: various religions (and conservative, liberal, or "cultural-only" expressions of those religions), as well as those who are anti-religious altogether or unsure of what "religion" (let alone "spirituality") even means. These kids come from quite a spectrum in familial stability as well, ranging from those for whom the phrase "my home" epitomizes love and safety, to those for whom it does the exact opposite; kids who are incredibly innocent of the cruelties, inequities, and hypocrisies of this world, and kids who have seen little else.

Yet for all of their differences, they are similar in this: once they feel sufficiently safe to start letting down defenses, they all absolutely delight in being childlike — in laughing, in playing games, in enjoying the outdoors; in building snowforts and hayforts; in splashing in puddles, hunting wild strawberries, and walking barefoot; in baking brownies and decorating cookies; in feeding chickens and hunting for eggs; in coddling horses or cuddling cats and dogs; in listening to stories read aloud; in having birds, animals, flowers, and insects pointed out and named; in marveling at the Milky Way and the fireflies and the sunset and the noisiness of the evening frogs. Be they toddler or teen. But what we've discovered is that whilst some of the children independently know how to enjoy doing these things — certainly those under, say six or seven — a surprising number (even from "safe" homes) don't. They have forgotten how, or are too fearful, or have succumbed to the cultural expectation that only little kids do these things. I have always delighted in helping adults remember/rediscover what it means to be childlike, but more and more frequently I meet children who just as desperately need help and/or permission. And they need it from an adult.

:::page break:::

|

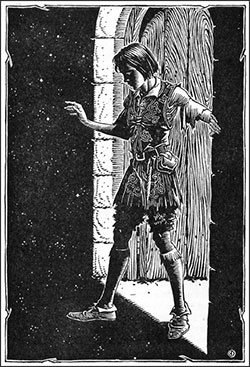

| Charles Folkard (1878-1963), from his 1949 edition of The Princess and Curdie, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. |

One of the most astute and beautiful writers upon the importance, indeed the holiness, of childlikeness (as C.S. Lewis repeatedly points out) is George MacDonald. MacDonald regularly explores the concept in tales such as The Back of the North Wind and Sir Gibbie. But the very first chapter of his Unspoken Sermons I discusses childlikeness with clear theological urgency, as he exegetes the moment when Christ takes a child into his arms, turns to the disciples (who'd just been disputing over which of them was greatest) and says: "unless you become as little children, you shall not enter the Kingdom of Heaven" (Matthew 18:3).

It had to have been rather an abrupt blow … one moment wrangling over who's the smartest, most worthy, most dedicated, most effective, most holy/religious/spiritual … and then: "unless you become as little children, you shall not enter the Kingdom of Heaven." Suddenly the need to understand "childlikeness" becomes pivotal; the fact that we might be confusing — or worse, obscuring from our children — the difference between childlikeness and childishness, becomes deeply concerning.