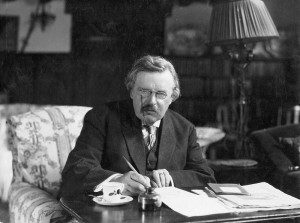

G.K. Chesterton

He was a joyful man. Everybody felt so. Simply to look upon him was to experience the oft-forgotten word: Mirth. British journalist and author, G.K. Chesterton’s exuberance, wit and charm were as large as his three hundred pound frame. He wrote puckish poems and humorous essays. He drank with the gruff (yet hilarious) Hilaire Belloc and exchanged clever poetry with his wife, Frances. Chesterton was the epitome of mirth. But he was also deadly serious. He argued (without quarreling) with intellectual giants like George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Clarence Darrow on matters of deep and lasting import. And while he could disarm his opponent with self-effacement and geniality, he would subsequently strike at the heart of the argument with uncanny precision and devastating effect. His weapon of choice? The endurance of Truth, the dignity of man, and the stubborn relevance of common sense.

“People do not know what they are doing because they do not know what they are undoing.”

– G.K. Chesterton

——————-

Evelyn Waugh

The British novelist Evelyn Waugh could be intimidating – to say the least. At times warm and at others sardonic, Waugh suffered few (if any) fools. His writing was a broadly appealing blend of the beautiful, the waggish and the wise. Before long, he rose like a rocket in the British literary world. As one work succeeded another, his wit and insight were indisputable. But as the modern world crowded around and crowned him with its laurels, Waugh’s unease would grow. The modern world’s judgment on matters great and small, he felt, was suspect. In time, his literary peers would be shocked. Evelyn Waugh would become a Catholic. And he would observe,

“Civilization – and by this I do not mean talking cinemas and tinned food, nor even surgery and hygienic houses, but the whole moral and artistic organization of Europe – has not in itself the power of survival. It came into being through Christianity, and without it has no significance or power to command allegiance…It seems to me that in the present phase of European history the essential issue is no longer between Catholicism, on one side, and Protestantism, on the other, but between Christianity and Chaos.”

——————-

T.S. Eliot

American expatriate/British author T.S. Eliot had the appearance of a prim, bookish businessman. Well-educated and well connected, he travelled in widely respected literary circles. After all, at the tender age of twenty-seven Eliot published a poem which broke conventions of style and substance and was highly regarded (and sponsored) by famed poet Ezra Pound. Shortly thereafter, Eliot made his name with his masterpiece, The Wasteland. The Wasteland is a poem that walks the reader from one scene of nihilism to the next, but unconventionally ends with a door cracked open to hope and meaning in its finals stanzas. And yet this embrace of hope in the midst of hopelessness did not emerge from a poet whiling away his hours in idyllic meadows and elitist salons. Rather, T.S. Eliot scraped daily as a subterranean London bank employee and nightly returned home to an ill and failing marriage. His poem was born of moments of joy punctuating days of nervous exhaustion. His life would be one of great success and raw pain. Years after T.S. Eliot would convert to Christianity (as a member of the Anglican Church), he would reflect on the Christian tradition of hope and its impact on a culture of nihilism,

“I do not believe that the culture of Europe could survive the complete disappearance of the Christian Faith. And I am convinced of that, not merely because I am a Christian myself, but as a student of social biology. If Christianity goes, the whole of our culture goes. Then you must start painfully again, and you cannot put on a new culture ready made. You must wait for the grass to grow to feed the sheep to give the wool out of which your new coat will be made. You must pass through many centuries of barbarism. We should not live to see the new culture, nor would our great-great-great-grandchildren; and if we did, not one of us would be happy in it.”

———————-

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers was not a likable sort. Bloated, disheveled and awkward, he testified about his unsavory background (as a former Communist) to an unpopular committee (House Committee on UnAmerican Activities) about an unpopular accusation (that the talented and dashing State Department official Alger Hiss was a Communist). Ultimately, Hiss would be convicted of perjury and later evidence, despite Hiss maintaining his innocence, would point to his guilt. Regardless, Chambers would walk away with his life forever changed and reputation tarnished. But regardless of the upending of his life and the fragmenting of the world he hoped for, Chambers observed,

“It is idle to talk about preventing the wreck of Western civilization. It is already a wreck from within. That is why we can hope to do little more now than snatch a fingernail of a saint from the rack or a handful of ashes from the [embers], and bury them secretly in a flowerpot against the day, ages hence, when a few men begin again to dare to believe that there was once something else, that something else is thinkable, and need some evidence of what it was, and the fortifying knowledge that there were those who, at the great nightfall, took loving thought to preserve the tokens of hope and truth.”

What did Chesterton, Waugh, Eliot and Chambers have in common? They believed, to their core, that the modern world isn’t right simply because it is modern. To believe otherwise would be bald chronological snobbery, or as Chesterton would incisively note,

“An imbecile habit has arisen in modern controversy of saying that such and such a creed can be held in one age but cannot be held in another. Some dogma, we are told, was credible in the twelfth century, but is not credible in the twentieth. You might as well say that a certain philosophy can be believed on Mondays, but cannot be believed on Tuesdays.”

In fact, the modern world is charged with remaining humble in the face of millennia of, as Russell Kirk would say, custom, convention and continuity. It is not the modern world’s place to casually sniff at what has come before and dismiss it with a wave of the hand and an upcurled lip. It is not for the modern world to carelessly declare prior judgments and practices parochial, narrow or even bigoted. Too often the modern world is impatient, impetuous and disinterested in honestly understanding what has come before. It is not for the Past to prove itself to the Present, but rather, the charge rests heavy on the shoulders of the Present (the modern world) to make their case (if any) against the Past, to intelligently and thoughtfully explain to previous generations of thinkers, writers, prophets and priests why they were so wrong. Often, once considered thoughtfully, modernity may find great virtues to be found in the Past, in tradition – that, in fact, there is a wise reason that tradition became tradition.

Without doubt the Present anticipates the Future. It is eager, with almost childlike enthusiasm, to see the wonders that will unfold. And that is as it should be. But the Present is also deeply rooted in and edified (and at times, appropriately chastened) by the Past. And that is as it should be. Chesterton observed that our modern democracy shouldn’t be so haughty as to disregard the vote of our ancestors – that, indeed, wisdom from the democracy of the dead can yet again come to assist the democracy of the living.

G.K. Chesterton’s greatest insight on this matter is as simple as an old fence.

“There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

That is the difference between a thoughtful reformer and a dangerous one. Consideration – deep consideration – of the wisdom of the past before acting on behalf of the future.

Perhaps as we move boldly into the future and gleefully celebrate what we are doing, we should pause and look back to consider what we may be undoing. As we shake off perceived shackles of confining civilization, we should be wary of unforeseen chaos. As we celebrate the fetters we leave behind, we should plunge our hands deep in our pockets to reclaim the fingernail or ashes of the civilizing saint we sorely need for the journey ahead. And perhaps as we prepare to clear away the unnecessary fence, we pause and think of why it is there at all.

Yes.

Perhaps.

——————————————-

Image Credits:

G.K. Chesterton – Wikimedia Commons

Evelyn Waugh – Wikimedia Commons

T.S. Eliot – Wikimedia Commons

Whittaker Chambers – Wikimedia Commons

Old Fence – Wikimedia Commons