“What is the character of your God?” At a certain point of spiritual development, deconstruction (saying what you reject, what you doubt, and what you disbelieve) is easier than construction (saying what you affirm, what you have faith in, and what you believe). So my challenge to myself and to you is to “live the (hardest) questions.” Some people speak of this practice as leaning into your “growing edge.” And this image of leaning into your growing edge resonates with the image/character of God I feel called to explore: an evolving, mysterious, and relational ‘God-in-process.’ Or perhaps God is prompting you to reflect on something completely different. As you look within yourself and reflect on the state of our world, how is God prompting you to live that question that is, for you, the hardest question?

Living the (Hardest) Questions:

What If God Is Not “Fully and Unambiguously Good?”

A Process Theology Sermon

God presides in divine council,

in the midst of the gods God holds judgement:

How long will you judge unjustly and show partiality to the wicked?

Give justice to the weak and the orphan;

Maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute.

Rescue the weak and the needy,

Deliver them from the hand of the wicked.

They have neither knowledge nor understanding,

they walk around in darkness;

I say,

You are gods, children of the Most High, all of you;

nevertheless, you shall die like mortals, and fall like any prince.

Rise up, O God, judge the earth; for all the nations belong to you!

Psalm 82

For last Sunday I skipped the final section of my sermon outline because the sermon was running long. As a brief reminder, our focus last week was the Parable of the Wedding Feast, which is particularly violent and disturbing in the Gospel of Matthew’s rendering. I invited you to consider the possibility that this parable was originally not a kingdom of God parable glorifying divine retribution, but instead a cautionary tale about kings such as Pharaoh, Herod, or Gaddafi, who are often vindictive, cruel tyrants. However, I did not have time to offer an image of God in contrast to the violent figure presented by Matthew’s Jesus.

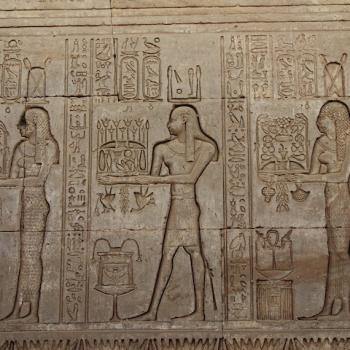

To begin to explore to a healthier image of God, biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan has called Psalm 82,

the single most important text in the entire Christian Bible…. It imagines a mythological scene in which God sits among the gods and goddesses in divine council. Those pagan gods and goddesses are dethroned not just because they are pagan, not because they other, nor because they are competition. They are dethroned for injustice, for divine malpractice, for transcendental malfeasance in office. They are rejected because they do not demand and effect justice among the peoples of the earth. And that justice is spelled out as protecting the poor from the rich, protecting the systemically weak from the systemically powerfully. Such injustice creates darkness over the earth and shakes the very foundations of the world.

With this perspective in mind, I invite you to hear again to the first part of this Psalm:

God presides in divine council,

in the midst of the gods God holds judgement:

How long will you judge unjustly and show partiality to the wicked?

Give justice to the weak and the orphan;

Maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute.

Rescue the weak and the needy,

Deliver them from the hand of the wicked.

Crossan highlights this Psalm as his response to the question, “What is the character of your God?” And the difference between how I understand the character of God and the way the character of the king is depicted in the Parable of the Wedding Feast is what made me think that last week’s parable was originally an anti-king parable that was co-opted as a “kingdom of God” parable through the vagaries of the oral tradition.

I first stumbled onto this idea through a blog called [TheHardestQuestion], which challenges pastors to ask — you guessed it — the hardest question they can think of about the scripture for the week. And, at least for me, the ‘hardest question’ regarding last week’s parable was not whether this story was originally an anti-king parable. That question is important (and, hence, why I structured last week’s sermon around it), but it is not the hardest question for me. Form Criticism and Empire Criticism are vital tools for interpreting scripture in the twenty-first century, but these methodologies are fairly comfortable for me after spending so much time with them in graduate school. The hardest question for me comes in the wake of rejecting the vengeful God of Matthew’s parable: “What is the character of your God?”

At a certain point of spiritual development, deconstruction (saying what you reject, what you doubt, and what you disbelieve) is easier than construction (saying what you affirm, what you have faith in, and what you believe). At this stage of faith development, the poet Rainer Marie Rilke advice is helpful:

have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

So my challenge to myself and to you this morning is to live the (hardest) questions. Some people speak of this practice as leaning into your “growing edge.”

And this image of leaning into your growing edge resonates with the image of God I feel called to explore: an evolving, mysterious, and relational ‘God-in-process.’ In this spirit, many of you will recall our Lenten study of Bruce Epperly’s book, Holy Adventure, which was an attempt to use a field of study called Process Theology to offer a progressive alternative to evangelical mega-church pastor Rick Warren’s bestselling book The Purpose Driven Life. Epperly writes that,

Warren charts a road map in which God chooses the most important events and encounters of our lives before we are born and without our input. Our personal calling, according to Warren’s vision, is to discover and live out God’s eternal purposes in our daily lives. We can find our true purpose only when we follow the directions and color inside the lines that God has already planned for us…. [In contrast,] I believe God’s holy adventure calls us to be creative and innovative right now as we listen for divine inspiration, and then to respond by coloring outside the lines and giving God something new as a result of our own personal artistry…. God calls us to become creative companions in God’s new and surprising creation. (21)

Instead of fear-based, anxiety-inducing theology, Epperly invites us to embrace our free will with creativity and imagination. Rather than conforming to a narrow, preordained path, his perspective calls us to a holy adventure in partnership with God.

Since the conclusion of our Lenten study, Epperly has released a new book called Process Theology: A Guide for the Perplexed, which is appropriate since much of the writing in this field of study is unfortunately difficult and technical reading.

As I read this latest volume, one passage stood out to me in particular regarding one of Epperly’s own teachers Bernard Loomer (1912-1985). Epperly writes that,

Rather than being fully and unambiguously good, as most process theologians assert, Loomer’s God is the ambiguous energy of creation, seeking the fullness of life, yet embracing both the creative and destructive aspects of the universe. According to Loomer, a fully concrete God of sufficient stature must be identified with the whole of life and not just the positive and life-supportive aspects of creation (14-15).

At the end of each week’s sermon, we pause for contemplative silence, and then enter into a time of conversation about what has resonated with you, excited you, or disturbed you in this week’s worship. And this passage stuck with me because it both excited and disturbed me.

We often rightly affirm with 1 John 4:16 that, “God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” Mystics from all ages and all religions have affirmed that love is at the beating heart of the universe. But process theologians are insistent that we affirm some form of panentheism, a theology that says God is ‘within, with, and beyond everything.’ This panentheistic approach is in contrast to dualistic theologies that depict God as ‘transcendent, above, and separate from the world.’ I think the Process perspective is right that God is not removed from the world, but is, in some sense, simultaneously ‘within, with, and beyond’ the world. But, if this claim is the case, how do we explain all the ‘evil’ in nature. If God with ‘within, with, and beyond’ everything in the universe, is God in destructive forces such as earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis?

On one hand, theologians remind us that there is much good and beautiful in the world, which can lead us to hypothesize a loving God at the helm of the universe. As we survey the world, at least from our twenty-first century, First World vantage point, we see that, “Most illnesses are curable. Most airplanes land safely. Most of the time, our children come home safely.”

But evolutionary biologists challenges us to consider the troubling aspects of seeing an ‘intelligent design’ behind natural processes: “an animal with webbed feet living on dry land…a bee that dies after stinging its prey, its stinger serrated in a way that prevents extraction after insertion…a cat apparently torturing a mouse before killing it” — in addition to the painful existence of death, injuries, and disease more generally.

Returning to the question of how we can understand God-in-everything, while also feeling resistance to the idea that God is in the destructive forces of natural disasters, death, and disease, theologian John Caputo wrote the following in the devastating aftermath of the 2004 Christmas Day tsunami in South Asia:

Predictably, many religious leaders have been rushing to the nearest microphone or camera to explain that, while these are all innocent victims, we cannot hope to explain the mystery of God’s ways — implying that this natural disaster is something God foresaw but for deeper reasons known only to the divine mind chose not to forestall. Others are telling us that God has taken this terrible occasion to remind us that we are all sinners and to dish out some much-needed and justifiable punishment to the human race.

Tell that to the father who lost his grip on this three-year-old daughter and watched in horror as she was carried out to sea.

Those are blasphemous images of God for me, clear examples of the bankruptcy of thinking of God as a strong force with the power to intervene upon natural processes like the shifting movements of the crustal plates around the Pacific rim as our planet slowly cools — the decision depending upon what suits the divine plan.

As a way of entering back into that moment, let us pause this sermon briefly to sing together Carolyn Winfrey Gillette moving hymn, written in the wake of that terrible storm:

O God, that Great Tsunami

Caputo’s book The Weakness of God: The Theology of the Event is his attempt to offer a constructive image of God that accounts for ‘natural evil’ such as devastating natural disasters, death, and disease. He writes that, in his understanding,

The power of God is not pagan violence, brute power, or vulgar magic; it is the power of powerlessness, the power of the call, the power of protest that rises up from innocent suffering and calls out against it, the power that says no to unjust suffering, and finally, the power to suffer-with…innocent suffering, which is perhaps the central Christian symbol.

Accordingly, a central word for process theologians is “lure.” God prompts us, lures us, and tries to persuade us, but, in this understanding, God does not have the power to coerce either us or nature.

Some may respond, “What good is such a ‘God?’” You may recall that in last week’s sermon we saw a pastoral theologian lead a woman through the process of naming that she was, in a sense, “morally superior” to a ‘God’ who would torture someone in hell for eternity (an infinite amount of time) for a finite sin. The point was that perhaps the image of God this woman had been taught at her church was not the actual God of the Universe, but instead a result of humans projecting their violent desires onto their image of God. And, in defense of the God of process theology, this theologian wrote these song lyrics,

So if what you’re looking for is a powerful God

who scatters his foes and bathes in their blood,

I’m afraid I’m not going to be much good to you.

But if what you need is somebody close by,

who suffers when you suffer,

and cries when you cry,

who cheers at your victories,

and hold you when you die,

then I’m there for you….

I find this image of God moving. Indeed, far from rejecting traditional Christian notions, many Christians find Process Theology compelling precisely because it helps them reconcile all those places in the Bible where God partners with humans, is effected by what humans do, and “changes God’s mind.”

At the risk of moving too far afield, Bernard Loomer’s conception of God as not “fully and unambiguously good,” but instead as “embracing both the creative and destructive aspects of the universe” is also highly consonant with some strains of Hinduism — such as the ‘Hindu Trinity’ of Brahma (“the creator”), Vishnu (“the sustainer”) and Shiva (“the destroyer/transformer”).

Through this lens we could perhaps begin to have “eyes to see” and “ears to hear” a more expansive vision of the Christian Trinity: God (“the co-creator”), Christ (“the redeemer”), and Spirit (“the transformer”), with implications of Spirit-led transformations that we — at least from our finite, human perspective — see as both ‘good’ and ‘evil.’ To name only one biblical precedent, we read in 1 Samuel 16:14 that, “the spirit of the Lord departed from Saul, and an evil spirit from the Lord tormented him.”

However, I have barely begun to work out the possible implications of such a view. But that’s the hardest question for me: “What is the character of your God?” Said differently, how do we understanding God in the twenty-first century in a way that does justice to the size of universe in which even our mind-bogglingly huge Milky Way galaxy is merely one among more than 100 billion other galaxies in the universe? How do we understanding God in way that, “embrac[es] both the creative and destructive aspects of the universe?”

I think in some ways this ‘hardest question’ has been one among many ‘hard questions’ that I have been living into for more than a decade. In early 1998, I was a college sophomore double majoring in religion and philosophy. I was learning to ask hard questions and enter into the global conversation of theologians and philosophers down through the ages. And while on a retreat with a popular evangelical campus religious group, I found myself confessing, in one of those late night campfire conversations, some of my emerging doubts.

I remember saying, “I’m not so sure about the lyrics of one of those songs we sang earlier. The chorus said about God, ‘For You are good / For You are good / For You are good to me.’ But these days I can’t say if I can affirm that whole line, ‘For You are good to me.’ I sometimes think that I can only say about God, ‘For You are.’”

Stunningly, the thirty-something-year-old leader of the group harshly responded to me that, “If I believed that I’d throw myself off a cliff.” Fortunately, I wasn’t suicidal. And looking back I think that her cruel tone resulted less from my particular words and more from me touching a nerve with some doubts she was repressing and feared hearing articulated. That episode was the beginning of the end of my involvement with that particular group. And my friends and I went on to found a more inclusive, open-minded group the next year called the Ecumenical Student Partnership. (And, yes, the tongue-in-cheek abbreviation E.S.P. is intentional!)

In the contemplative silence to follow, I invite you to consider, not only what you doubt about God, but also what you believe about God. Sure, God is love, and God is good. But could God also be in both the creativity and the destruction? As the Franciscan monk Richard Rohr has written: “At this point, God becomes more a verb than a noun, more a process than a conclusion, more an experience than a dogma, more a personal relationship than an idea. There is Someone dancing with you now, and you are not afraid of making mistakes.” Or perhaps God is prompting you to reflect on something completely different. In the silence, as you look within yourself and reflect on the state of our world, how is God prompting you to live that question that is, for you, the hardest question?

For Further Reading

- Carl Gregg, “A Performance of Those Things Which Were Told” (Luke 1:39-45). An excerpt:

There seems to be, among other things, an overall trajectory in the direction of increasing complexity [in the universe]. For example, Roman Catholic theologian John F. Haught offers a brief summary of the major evolutionary emergences in eight stages: “pre-atomic, atomic, molecular, unicellular, multi-cellular, vertebrate, primate, and human.”This directionality of increasing complexity points us toward a divine dance of the universe that is grounded in the rhythms of life, birth, and hope.

Available at broadviewchurch.net/2010/12/sermon-a-performance-of-those-things-which-were-told-luke-139-45/.

- Jesus, Jazz, and Buddhism: http://www.jesusjazzbuddhism.org/. This website posts articles that are at the intersection of East-West dialogue.

- If you are especially interested in continuing the conversation begun with this sermon, consider attending the Emergent Village Theological Conversation 2012 in Los Angeles, California at the end of January, the focus of which will be Process Theology. For more, visit http://www.processtheology.org/sample-page/.

Notes

1 “last week’s sermon” — see “Happy Halloween Homily: A Spooky-Scary, Empire-Critical Reading of the Parable of the Wedding Feast: How an Anti-King Parable Was Co-opted as a Kingdom of God Parable.” Available at http://www.patheos.com/community/carlgregg/2011/10/31/how-an-anti-king-parable-was-co-opted-as-a-kingdom-of-god-parable-occupywallst/

2 “Matthew’s Jesus” — a common formulation used as a reminder that there is often a difference between the ‘historical Jesus’ and the way Jesus is presented in Matthew’s Gospel (or any other narrative), which, in Matthew’s case, was compiled more than fifty years after the life of the historical Jesus.

3 “vagaries of the oral tradition” — see “Part II: Memory and Orality” in John Dominic Crossan, The Birth of Christianity : Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus. A few excerpts:

- “The overwhelming probability is that most of what Jesus said, he said not twice but two hundred times with (of course) a myriad of local variations” (N.T. Wright, qtd in 49).

- “First, memory is creatively reproductive rather than accurately recollective. Second, orality is structural rather than syntactical. Apart from short items that are retained magically, ritually, or metrically verbatim, it remembers gist, outline, and interaction of elements, rather than detail, particular, and precision of sequence” (55).

- “In studies of eyewitness testimony, the most favorable estimates of the correlation between confidence and accuracy are about .40” (Experiment, qtd in 68).

- “The assumption that nonliterate cultures encourage lengthy verbatim recall is the mistaken projection by literates of text-dependent frames of reference” (Hunter, qtd in 69).

4 “The Hardest Question” — for a more detailed description, see the blog’s self-description at http://thehardestquestion.org/about-2/.

5 “spiritual development” — on the “Stages of Faith Development,” see my sermon “Everything Is Holy Now” at http://broadviewchurch.net/2011/09/new-sermon-everything-is-holy-now/.

6 “live the questions” — see Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (1903).

7 “growing edge” — for interview with spiritual teachers leaning into their growing edge, see Sounds True’s podcast Insights at the Edge at http://www.soundstrue.com/podcast.

8 Process Theology — for more on the benefits of a Process perspective, see Bruce Epperly’s post, “Ponderings on a Faith Journey: Why Progressive Christianity Needs Process Theology.” Available at http://pastorbobcornwall.blogspot.com/2011/10/why-progressive-christianity-needs.html. For a video interview, with Epperly, see http://www.emergentvillage.com/weblog/process-theology. See also Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki’s free, short e-book What Is Process Theology? A Conversation with Marjorie. Available at http://processandfaith.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/What_Is_Process_Theology.pdf?t=1319911881.

9 “Loomer’s theology” — see The Size of God: The Theology of Bernard Loomer in Context, edited by William Dean and Larry Axel.

10 “God is love” — see Karen Armstrong, “Charter for Compassion.” An excerpt: “The Charter for Compassion is a document that transcends religious, ideological, and national difference. Supported by leading thinkers from many traditions, the Charter activates the Golden Rule around the world.” Available at http://charterforcompassion.org/.

11 “The Problem of Evil” — The traditional theological word for this dilemma is theodicy. For a succinct overview of this problem, see “Stephen Law on The Problem of Evil.” Available at http://philosophybites.libsyn.com/stephen_law_on_the_problem_of_evil.

12 “there is much good in the world” — Harold Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, 152.

13 “evolutionary biologists” — see Karl Giberson, Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution, 32.

14 “tsunami” — see John Caputo, The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event (Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Religion), 2009:xi. For a more accessible Caputo book, see What Would Jesus Deconstruct?: The Good News of Postmodernism for the Church (The Church and Postmodern Culture).

15 “The power of God is not pagan violence” — see Caputo (2009), 43.

16 “infinite amount of time) for a finite sin” — The philosopher Bertrand Russell famous made a similar argument in his essay “Why I Am Not a Christian,” 13.

17 “Mabry sings” — see John Mabry, The Monster God: Coming to Terms with the Dark Side of Divinity, 160.

18 “changes God’s mind” — see Lewis Ford, Lure of God: A Biblical Background for Process Theism. See also my letter to the editor, “God Does Change.” Available at http://www.patheos.com/community/carlgregg/2011/08/25/letter-to-the-editor-god-does-change/. Process Theology is philosophical in its origins, and there is a related perspective in evangelical theology called “Open Theism” that emerged precisely because of the many biblical passages in which God is starkly different from the removed, transcendent, judge of some theological camps. Many of these theologians think that Christian theology allowed itself to be infected by the surrounding Greco-Roman theology that praised the static perfection of Plato’s forms or viewed God, in Aristotle’s terms, as the “Unmoved Mover.” In contrast, evangelical theologian Clark Pinnock says that God is instead the “Most Moved Mover” — see Most Moved Mover: A Theology of God’s Openness (Didsbury Lectures).

19 Hinduism — Process thought may be even more in synch with Taoism. Consider how this opening passage could lend us insight into the Mystery of God (or the Godhead):

The tao that can be told

is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal Name.

The unnamable is the eternally real.

Naming is the origin

of all particular things.

Free from desire, you realize the mystery.

Caught in desire, you see only the manifestations.

Yet mystery and manifestations

arise from the same source.

This source is called darkness.

Darkness within darkness.

The gateway to all understanding.

Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching: A New English Version, Stephen Mitchell (translator). See also John Mabry, God As Nature Sees God: A Christian Reading of the Tao Te Ching.

In addition, Carrie Newcomer’s song “I Do Not Know Its Name” gestures toward a way to understand God through the lens of Taoism. She writes about the song that, “The opening lines of the Tao Te Ching are translated as ‘The Tao that can be expressed is not the Everlasting Tao. . .The Name that can be named is not the Everlasting Name.’ This song is a little hymn to mystery and the mysterious.” Notice in the following excerpt that she, in essence, responds to the question “What is the character of your God” through multiples senses:

I do not know its name / ‘though it’s ever intertwining, / and I believe it must look like an old man shining…. / I do not know its name / no matter how I try / But I think it must taste like peaches eaten by the roadside…. / I do not know its name / Elusive and subtle, / But I believe it must sound like that man singing in the shuttle. / Standing in the river barefoot in the current, / I hear a birdcall and try to learn it. The water is a wonder, it’s cold and fast and deep…. / I do not know its name, / Swimmer or watcher. / But I believe that there is always something, / Moving beneath the water…. / If holy is a sphere that cannot be rendered, / There is no middle place because all of it is center / I do not know its name / I do not know its name / I do not know its name.

The full lyrics are available at

http://www.carrienewcomer.com/lyrics/Newcomer_Before_and_After_Lyrics.pdf.

You can listen to the song at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=umD1pZi7JAE.

20 see as both ‘good’ and ‘evil.’ — see Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality (translated by Maudemarie Clark and Alan J. Swensen). For an appreciative and constructive critique of Nietzsche, see Merold Westphal, Suspicion and Faith: The Religious Uses of Modern Atheism.

21 “more than 100 billion other galaxies” — Carl Sagan, Billions & Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium, 56.

22 “For you are good” — the song in question is Craig Musseau, “Good To Me.” The full lyrics are available at http://www.worship.co.za/ww/ww-0108.asp. You can listen to the song at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mpi4s2kvqnU.

23 “doubts she was repressing and was fearful of hearing articulated” — see Carl Jung on the “shadow.” Anthony Stevens, Jung: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions).

24 “There is Someone dancing with you now, and you are not afraid of making mistakes.” — Richard Rohr, The Naked Now: Learning to See as the Mystics See, 23. Thus, perhaps in an ‘adult religion’ in the twenty-first century, God is less to be ‘worshipped’ and God is more Someone with whom to partner in co-creating the world and the future. For more, I highly recommend Ken Wilber’s audio recording, The One Two Three of God. For those who appreciate this quote, I also highly recommend Richard Rohr’s daily e-mail meditations, available at: http://www.cacradicalgrace.org/richard-rohr/dailymeditations.

The Rev. Carl Gregg is the pastor of Broadview Church in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook(facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

I welcome your feedback in the comments section.