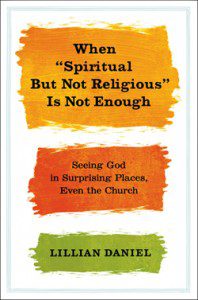

Almost two years ago Lillian Daniel, the Senior Minister of First Congregational Church of Glen Ellyn, Illinois, wrote a short blog  for the Huffington Post — a mere 374 words — titled, “Spiritual But Not Religious? Please Stop Boring Me.” For whatever confluence of reasons, that blog post went viral and was expanded into a book she published this past year titled When “Spiritual but Not Religious” Is Not Enough: Seeing God in Surprising Places, Even the Church.

for the Huffington Post — a mere 374 words — titled, “Spiritual But Not Religious? Please Stop Boring Me.” For whatever confluence of reasons, that blog post went viral and was expanded into a book she published this past year titled When “Spiritual but Not Religious” Is Not Enough: Seeing God in Surprising Places, Even the Church.

This past summer, the Unitarian Universalist Minister’s Association invited Daniel to be a keynote speaker at this year’s Ministry Days, which is a two-day conference for UU ministers held immediately before each year’s UU General Assembly. There were hundreds of UU ministers registered for this conference. (Food for thought: if you had the power to put one speaker in front of a captive audience of hundreds of UU Ministers whom would you choose?)

While I don’t know that Lillian Daniel has “the answer” for what Unitarian Universalism needs to fully bloom in the coming years and decades, I do think that she has wisdom to share. As you read through this excerpt from her viral blog post, what parts resonate with you, either positively or negatively?

On airplanes, I dread the conversation with the person who finds out I am a minister and wants to use the flight time to explain to me that he is “spiritual but not religious.” Such a person will always share this as if it is some kind of daring insight, unique to him, bold in its rebellion against the religious status quo.

Next thing you know, he’s telling me that he finds God in the sunsets. These people always find God in the sunsets….. Being privately spiritual but not religious just doesn’t interest me. There is nothing challenging about having deep thoughts all by oneself. What is interesting is doing this work in community, where other people might call you on stuff, or heaven forbid, disagree with you. Where life with God gets rich and provocative is when you dig deeply into a tradition that you did not invent all for yourself.

Thank you for sharing, spiritual-but-not-religious sunset person. You are now comfortably in the norm for self-centered American culture, right smack in the bland majority of people who find ancient religions dull but find themselves uniquely fascinating. Can I switch seats now and sit next to someone who has been shaped by a mighty cloud of witnesses instead? Can I spend my time talking to someone brave enough to encounter God in a real human community? Because when this flight gets choppy, that’s who I want by my side, holding my hand, saying a prayer and simply putting up with me, just like we try to do in church.

You can’t make this stuff up. There are limits to self-made religion.

You may recall that the subtitle to this online rant is “Please Stop Boring Me.” In her book Daniel elaborates that:

When I meet a teacher, I don’t feel the need to tell him that I always hated math. When I meet a chef, I don’t need to tell her that I can’t cook. When I meet a clown, I don’t need [to] tell him that I think clowns are all scary…. But everybody loves to tell a minister what’s wrong with the church, and it’s usually some church that bears no relation to the one I am proud to serve. (3)

One reviewer of her book continued in this vein about ministers like Daniel, who have become exasperated with yet one more person describing themselves as “Spiritual But Not Religious”:

One could imagine how a doctor would feel if he heard ninety-eight people say, “I don’t really go to doctors anymore. I just consult a website.” Or how a politics or history professor would feel after ninety-nine people say, “Universities are really outdated now that we have Cable News and talk radio.”

“Please stop boring me” indeed.

But setting aside the sarcastic tone, here’s my takeaway from Daniel’s provocative post. I think her final sentence is right: “There are limits to self-made religion.” Daniel is snarky in her critique of the “Spiritual But Not Religious,” but underneath the snark is a prophetic call to community.

That being said, there is an important reason that the First Principle of Unitarian Universalism is “The inherent worth and dignity of every person.” And that First Source of Unitarian Universalism is “Direct experience….” The choice to prioritize individual worth and individual experience is understandable since our religious freedom was hard won by previous generations who courageously questioned the legitimacy of entrenched religious authorities, risking their freedom and sometimes their lives to do so. But what I hear Lillian Daniel trying to do is invite us to consider if we have moved too far in the other direction.

While she does mock people who “find God in the sunsets,” she later confesses in her book that, of course, she too finds deep meaning and beauty in connecting to nature (6). But her frustration is that so much more is possible beyond the bounds of isolated, individualistic religious experience. As important as firsthand religious experience is, community is even more often a catalyst for personal growth. In Daniel’s words: “What is interesting is doing this work in community, where other people might call you on stuff.”

She continues, “Where life with God gets rich and provocative is when you dig deeply into a tradition that you did not invent all for yourself.” And even though the consolidated religion of Unitarian Universalism dates back only to 1961 (although its component parts of Unitarianism and Universalism date back centuries), no one person “invented” Unitarian Universalism; individuals are merely part of this larger movement. And to take the UU congregation where I minister as an example, we have active and prominent affiliate groups that include Atheist/Humanist/Agnostics, UU Buddhists, UU Christians, and UU Pagans — and we’re in the initial stages of starting a group for UU Jews. As opposed to being spiritual in isolation, how much more vital and challenging is it to work out who you are, what you believe, and what your place is in the universe amidst such a wide-ranging hubbub of worldviews? And I’m always fascinated to see how much overlap there is between those groups and how many members of my congregation regularly attend two of more of those diverse groups because they find multiple ones of these paths to be meaningful and mutually formative.

But I know there are also times when various members of UU congregations wish that their congregation had more Atheism and Humanism or less Christianity and Paganism — or vice-versa. But as Daniel says, “What is interesting is doing this work in community, where other people might call you on stuff.” Being part of a Unitarian Universalist congregation that draws explicitly on six sources helps keep individuals honest, challenges biases, and helps prevent the tribalistic myopia that can descend when you spend too much time around people that think the same way you do.

Daniel clarifies in her book that at the root of her frustration is those in the “Spiritual But Not Religious” set, who think their rejection of religion in favor of personal spirituality makes them radical — whereas in the twenty-first century West, doubt and individualism doesn’t make you radical; it just makes you a standard-fare, middle-of-the-road Protestant (4), which actually was radical back in the sixteenth-century. In contrast, I invite you to consider that being “Spiritual And Religious” is a more radical and more needed in our age than being “Spiritual But Not Religious.”

When I was in seminary and we would occasionally sleep in and skip a Sunday morning service, we would sometimes joke that we had attended “The Church of the Holy Comforter” or “The Church of The New York Times.” Along these lines Wendell Berry famously published a book titled A Timbered Choir of poems inspired by long Sunday morning walks through the woods that he had taken instead of attending a religious service. And there have been times in my life when I needed to sleep in, go running, read The New York Times, or enjoy a leisurely brunch at the end of a long week instead of going to a religious service. But in our increasingly individualized world of computer screens and smart phones, the most radical choice is not individualized doubt, but choosing the hard work of being in diverse community.

To return briefly to Lillian Daniel’s sarcastic tone, she has said in an interview that,

Any idiot can find God alone in the sunset. It takes a certain maturity to find God in the person sitting next to you who not only voted for the wrong political party but has a baby who is crying while you’re trying to listen to the sermon. Community is where the religious rubber meets the road. People challenge us, ask hard questions, disagree, need things from us, require our forgiveness. It’s where we get to practice all the things we preach.

What is radical today is the move from dependence on our birth community through the struggle of individuation and independence to a mature freely chosen interdependence that often only authentically comes on the far side of independence. In our time, that third step of moving from independence to interdependence is the radical part. As the late UU minister Forrest Church summarized, “In developmental theory, the progression goes as follows: dependence, independence, interdependence.”

And to reflect some on how being both spiritual and religious relates to this move toward interdependence, the word religion comes from adding the Latin prefix re– (meaning “again”) to the root ligare (meaning “bind or connect”). So the etymological root of the word religion means to “bind together again” or “to re-connect.” But if you are transitioning from the dependent stage of your life to an independent stage, then religion — especially certain forms of religion — can feel like a constricting attempt to bind you back into a role of dependence that you are doing your best to escape. From that place of longing for freedom and independence, you may find yourself declaring authentically that you are “spiritual, but not religious,” at least not religious in this earlier, dependent sense. Because being “religious but not spiritual” — blindly supporting institutionalized religion — is arguably far worse than being “spiritual, but not religious.”

But if you stay too long in that middle stage of “spiritual, but not religious,” your self-made spirituality can devolve into an unhealthy narcissism of entitlement and self-involvement. Even more importantly, a prolonged fixation on independence can block you from being involved with the hard work of building community. And it is not isolated, independent individuals, but communities of people working together across diverse differences who most often transform this world for the better. Along these lines, many people think of Buddhism as religion of isolated individuals meditating alone on their cushions. But a mature Buddhism also has at its core the practice sangha, which is the Sanskrit word for a community of Buddhist practitioners.

At the same time, surveys keep being released with increasing numbers of people identifying their religion as “None” or “spiritual, but not religious.” But in our individualistic age, community really matters. And I believe that Unitarian Universalism offers a way of choosing a mature interdependence on the other side of independence — of being spiritual and religious. And I think it is significant that surveys also show that overall membership in the Unitarian Universalist Association has increased by 1.9% a time when many major American denominations have seen shocking drops in membership:

the Presbyterian Church USA, was down 27.3% from 2004–2012, the United Church of Christ (down 25.8%), the Episcopal Church (down 19.6%), the Evangelical Lutheran Church (down 17.9%), and the American Baptist Church USA (down 13.5%”).

The better news, for UUs, would be if the UUA were seeing a sharper increase, but I’ll take a relatively steady flatline over a decline any day. [There is unfortunately not room in this post to drill down into all the different reasons for the respective declines in the above denominations, although some of them relate to more conservative congregations leaving as these more progressive groups have moved toward in a greater inclusion of women and LGBT Christians at all levels.]

I would also be remiss in this post if I did not mention a paradigm-shifting, historic example of the power of being spiritual and religious. This Wednesday, August 28 is the 50th Anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. And the Civil Rights Movement in this country is a strong example of the power of beloved community: the transformative community that can be found at the intersection of prophetic spirituality, social justice, and diverse community. As Cornel West has said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.”

But seeking interdependence on the other side of independence, being spiritual and religious, and seeking both love and justice is rarely easy. And as one commentator has written, we must be wary of falsely sentimentalizing the memory of Dr. King:

When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. took the podium on August 28, 1963, the Department of Justice was watching. Fearing that someone might hijack the microphone to make inflammatory statements, the Kennedy DOJ came up with a plan to silence the speaker, just in case. In such an eventuality, an official was seated next to the sound system, holding a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” which he planned to play to placate the crowd…. Relatively few people know or recall that the Kennedy administration tried to get organizers to call it off; that the FBI tried to dissuade people from coming; that racist senators tried to discredit the leaders; that twice as many Americans had an unfavorable view of the march as a favorable one…. Before his death, King was well on the way to being a pariah. In 1966, twice as many Americans had an unfavorable opinion of him as a favorable one. [In 1967,] Life magazine branded his anti–Vietnam War speech at Riverside Church “demagogic slander” and “a script for Radio Hanoi.

Relatedly, to quote Cornel West again about his reticence about plans for the 50th Anniversary celebration for the March on Washington:

we really don’t like to admit the degree to which Martin Luther King, Jr. was as much anti-war and anti-empire as he was anti-racist…. You’ll hear a whole lot of talk [around the 50th anniversary] about the gutting of the Voting Rights bill. There’s nothing wrong with talking about the gutting of the Voting Rights bill but that’s not all of Martin, you’re truncating Martin if you limit it to that.

Indeed, in his 1967 book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? — his fourth and last book published before his assassination — Dr. King wrote about the interrelated “triple evils” of poverty, racism, and militarism.

And if we are going to continue to turn Dr. King’s dream into deeds, we need each other. Isolated individuals cannot overcome those triple evils of poverty, racism, and militarism. A self-made, individualized religion of sunsets, sleeping in, and long walks won’t suffice; it will barely get us started. But together, we are do more than any of us are capable of alone.

“Let freedom ring.”

Each of us must move through the fires of independence.

“Let freedom ring.”

But freedom and independence is not the end of the story. As Dr. King said, “the end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the Beloved Community.”

Notes

1 For my blog post about Lillian Daniel’s keynote address to the UU Minister’s Association, see “Spiritual and Religious: Highlights from Lillian Daniel among the UUs,” available at http://www.patheos.com/blogs/carlgregg/2013/06/spiritual-and-religious-highlights-from-lillian-daniel-among-the-uus/.

2 When the late sociologist of religion Robert Bellah spoke before the UU General Assembly in 1998, he challenged Unitarian Universalists to reverse the order of our first and seventh principles: “give up ontological individualism and affirm that human nature is fundamentally social. That would mean making ‘the interdependent web of all existence’ the first of your principles and not the last.’” See, “Unitarian Universalism in Societal Perspective,” available at http://www.robertbellah.com/lectures_7.htm.

3 “In developmental theory” — Forrest Church, The Cathedral of the World: A Universalist Theology, 134. In general, I highly recommend the entire book, but in regard to this post, see especially the essay from which the quote is drawn, “Emerson’s Shadow,” pages 132-139.

4 “A Pew Research Center survey in 2012 found that the number of people who are not affiliated with a religion had increased 5 percent since 2007. That same survey found 18 percent of Americans identified themselves as spiritual but not religious, while 59 percent identified as both, and just 5 percent said they were religious but not spiritual.”

For more, a free webinar is available on “Growth 110: Growth 110: Living in a Spiritual But Not Religious World” at http://www.cerguua.org/moodle/.

5 The fuller quote from Cornel West is “Just as justice is what love looks like in public and tenderness is what love feels like in private, deep democratic revolution is what justice looks like in practice,” available at http://occupiedmedia.us/2011/11/a-love-supreme/.

6 be wary of falsely sentimentalizing the memory of Dr. King — Gary Younge, The Nation, “The Misremembering of ‘I Have a Dream,’” available at http://www.thenation.com/article/175764/misremembering-i-have-dream#axzz2ctXmT4BE.

7 “King, Jr. was as much anti-war and anti-empire as he was anti-racist” — Cornel West from a transcript of Tavis Smiley and Cornel West, “The Oratorical Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” available at https://soundcloud.com/smileyandwestshow/the-oratorical-legacy-of.

8 “triple evils” — A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., “Facing the Challenge of a New Age” (1957), 250.

9 “the end is Beloved Community” — A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., “Facing the Challenge of a New Age” (1957), 140.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles