A man died. The people who knew him gathered to share memories. Finally, a portrait was commissioned. But as generations passed, the painting did not seem fine enough. The heirs of the portrait, who had become wealthy, created a new golden frame, immense, carved with motifs from the portrait and encrusted with jewels. People began to feel that the old portrait of that dark fellow with the haunting eyes pulled the effect down. As it began to peel from age, they extended the frame inward. One day the frame covered the whole canvas.

—Catherine Keller, On the Mystery: Discerning Divinity in Process, 133

This post is the third in a four-part series on “A Journey with Four Spiritual Guides: Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, and Ramakrishna.” One of the central points I made in the previous post was that the term Buddha is a title meaning “Awakened One.” And 2,500 years ago, the intention of the first Buddha, a human named Siddhartha Gautama, was not to make Buddhists, but to make more Buddhas — more “Awakened Ones,” who would experience, as he had, that there is a way of gaining liberation from suffering through what he called the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path. Keep that word path in mind because a similar dynamic happened with the historical Jesus, who did not intend to create Christians, a term that wasn’t coined until after Jesus’ death (Acts 11:26). Instead, the earliest followers of Jesus were called followers of “The Way” (Acts 9:2). The invitation of “Jesus as spiritual guide” is not about worshiping Jesus. Instead, it is about living in the world in a similar way to how he live: a way of generous, transformative, risky love. As in the opening “Parable about Jesus,” religious traditions over time can become ossified, self-interested institutions. But keep those words path and way in mind. They can help lead us back to the dynamic, beating heart of religious experience that helped found our various world religious traditions in the first place — inviting us to test and experience in the crucible of our own firsthand experience what Jesus, Buddha taught was possible to experience about ourselves, this world, and one another. Looking at the historical Jesus in particular, one complication of following the “Way” of Jesus is that if you try to get specific about who Jesus was, the competing narratives quickly become complex. Indeed, one of my favorite historical Jesus scholars, John Dominic Crossan has confessed that, “historical Jesus research is becoming something of a scholarly bad joke…[because of] the number of competent and even eminent scholars producing pictures of Jesus at wide variance with one another” (xxvii). Or as I saw on Twitter last week: “Somewhere between ‘The Passion of the Christ’ and ‘Life of Brian’ is the truth” of who Jesus actually was. The Southern Baptist Christianity of my childhood leaned more to The Passion of the Christ side of the equation: the importance of believing that Jesus’ violent death was a necessary sacrifice for the forgiveness of humanity’s sins. This perspective has been criticized as Vampire Christianity: only wanting Jesus for his blood. All joking aside, I could not be more serious that there is a strong argument on the side of the contemporary theologians who argue that the idea of God accepting the violent death of God’s son as necessary for the salvation of humanity would be the equivalent of divine child abuse. And at the risk of oversimplification, I have come to appreciate the distinction some scholars make between “The Death Tradition” and “The Life Tradition” in Christianity. Both of these frameworks have been active and competing in Christianity for the past two thousand year. The Death Tradition emphasizes the need to believe in the saving power of Jesus’ violent death to determine whether one will end up in heaven or hell in the afterlife. The focus is more on Jesus’ death than his life and more on the next world instead of this world. A consummate example of “The Death Tradition” is the Nicene Creed, written three centuries after Jesus’ life, which asks Christians to confess their belief that Jesus: “came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again…..” Notice what is missing from that creed: Jesus’ life and teachings! It skips straight from his birth to his crucifixion. In essence, as I’ve heard it sometimes said, the entire Life Tradition is squeezed into a comma in the Nicene Creed! Turning our attention to the “Life Tradition,” this paradigm emphasizes the perennial wisdom in Jesus’ teachings and the radical risks he took during his life to defy corrupt religious authorities, challenge antiquated religious traditions, and be in solidarity with the marginalized. In my religious tradition, the Universalist half my Unitarian Universalist heritage grew out of the “Life Tradition” of Christianity. It began with rejecting the idea that anyone could be damed to hell for all eternity. Overtime, the emphasis shifted from teaching universal salvation in the next world to working for universal salvation for all people in this world. The bumper sticker version of contemporary Universalism is “Love the hell out of this world.” And given the prominence of the Death Tradition in Christian history, it is often important to emphasize that the Life Tradition has been present from the beginning. In the first chapter of Mark, the earliest canonical Gospel, verse fourteen says, “After John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God,and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.’” Jesus is not proclaiming the good news of his impending crucifixion so that his death may be an atoning sacrifice for humanity’s sins. Instead, at the beginning of the earliest recorded Gospel, Jesus is proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God — a way of building a diverse community across traditional boundaries that Martin Luther King, Jr. called the “Beloved Community.” The Life Tradition emphasizes that Jesus did not want to die, but he was willing to live in such a “Way” that risked him being killed because he believed so passionately in working for greater social and economic justice. John Mabry, a theologian in the Life Tradition says it this way:

importance of believing that Jesus’ violent death was a necessary sacrifice for the forgiveness of humanity’s sins. This perspective has been criticized as Vampire Christianity: only wanting Jesus for his blood. All joking aside, I could not be more serious that there is a strong argument on the side of the contemporary theologians who argue that the idea of God accepting the violent death of God’s son as necessary for the salvation of humanity would be the equivalent of divine child abuse. And at the risk of oversimplification, I have come to appreciate the distinction some scholars make between “The Death Tradition” and “The Life Tradition” in Christianity. Both of these frameworks have been active and competing in Christianity for the past two thousand year. The Death Tradition emphasizes the need to believe in the saving power of Jesus’ violent death to determine whether one will end up in heaven or hell in the afterlife. The focus is more on Jesus’ death than his life and more on the next world instead of this world. A consummate example of “The Death Tradition” is the Nicene Creed, written three centuries after Jesus’ life, which asks Christians to confess their belief that Jesus: “came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again…..” Notice what is missing from that creed: Jesus’ life and teachings! It skips straight from his birth to his crucifixion. In essence, as I’ve heard it sometimes said, the entire Life Tradition is squeezed into a comma in the Nicene Creed! Turning our attention to the “Life Tradition,” this paradigm emphasizes the perennial wisdom in Jesus’ teachings and the radical risks he took during his life to defy corrupt religious authorities, challenge antiquated religious traditions, and be in solidarity with the marginalized. In my religious tradition, the Universalist half my Unitarian Universalist heritage grew out of the “Life Tradition” of Christianity. It began with rejecting the idea that anyone could be damed to hell for all eternity. Overtime, the emphasis shifted from teaching universal salvation in the next world to working for universal salvation for all people in this world. The bumper sticker version of contemporary Universalism is “Love the hell out of this world.” And given the prominence of the Death Tradition in Christian history, it is often important to emphasize that the Life Tradition has been present from the beginning. In the first chapter of Mark, the earliest canonical Gospel, verse fourteen says, “After John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God,and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.’” Jesus is not proclaiming the good news of his impending crucifixion so that his death may be an atoning sacrifice for humanity’s sins. Instead, at the beginning of the earliest recorded Gospel, Jesus is proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God — a way of building a diverse community across traditional boundaries that Martin Luther King, Jr. called the “Beloved Community.” The Life Tradition emphasizes that Jesus did not want to die, but he was willing to live in such a “Way” that risked him being killed because he believed so passionately in working for greater social and economic justice. John Mabry, a theologian in the Life Tradition says it this way:

Rosa Parks is an imitator of Christ, not because she suffered for taking her stand (or keeping her seat, in her case), but because she had the courage to believe in her own dignity and fought for it in spite of the conflict that resulted. Nelson Mandela is an imitator of Christ, not because he suffered in prison, but because he held out for peace and justice, and led a nation to resurrection. In each case it is not the suffering that is redemptive, but the courage to pursue justice in the face of pain and evil. (129)

In contrast, the Death Tradition has often taught that Jesus not only had to die, but also had to suffer horribly to satisfy God’s wrath. To use an old Buddhist saying, “Don’t Mistake the Finger Pointing at the Moon for the Moon.” And the Death Tradition in Christianity has too often fixated on the person of Jesus and missed that the historical Jesus was always pointing beyond himself toward the one he called “God” and toward a subversive way of building community based on generosity, compassion, and justice instead of the Roman Empire’s model of hierarchy, dominance, and violence. Jesus’ life and teaching were pointing not to him as a single, male figure to be worshipped (a highly problematic notion in many ways!); he was pointing beyond himself to a way of building the Beloved Community. But that vision of building the Beloved Community is not easily realized then or now. One of the primary tools in following the way of Jesus (in doing what he did) is building community across socio-economic boundaries through eating meals with anyone: friends, enemies, or strangers. (A practice that came to be called the Lord’s Supper, Communion or Eucharist.) To give you a taste of what it might mean to following Jesus as a spiritual guide today, Crossan says:

Think, for a moment if beggars came to your door, of the difference between giving them some food to go, of inviting them into your kitchen for a meal, of bringing them into the dining room to eat in the evening with your family, or of having them come back on Saturday night for supper with a group of your friends. Think, again, if you were a large company’s CEO, of the difference between a cocktail party in the office for all the employees, a restaurant lunch for all the middle managers, or a private dinner party for your vice presidents in your own home. Those events are not just ones of eating together, of simple table fellowship, but are…a map of economic discrimination, social hierarchy, and political differentiation. (61)

And when you start transgressing those socio-economic norms, you risk getting into trouble. In Jesus’ case, his transgressions against the unjust status quo of his day eventually got him executed by the Roman powers that be. Likewise, individuals and groups who want to maintain the unjust status quo in our own day contributed to the deaths of contemporary Jesus-like figures from Gandhi to Oscar Romero to Martin Luther King, Jr. At the same time in talking about the “Way” of Jesus as spiritual guide, it is important to remember that neither Jesus, nor any of those figures I just mentioned were perfect. Despite all their wisdom, courage, and renown, they get it wrong sometimes too, like the rest of us humans. Most famously, there’s the story in Mark 7 in which Jesus refuses to heal the daughter of a Syrophoenician woman because she was Gentile instead of Jewish. Jesus’ heart is initially hardened toward her, and he says, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” (If you are wondering, yes, some commentators have said that Jesus is calling the woman a “bitch,” a female dog.) Fascinatingly, this Gentile woman rebukes Jesus, saying, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” Jesus, moved by her boldness, heals her daughter. In the words of theologian Letty Russell, this episode is an example of Jesus getting “Caught with his compassion down” (162). Looking beyond the life of the historical Jesus, one of the many powerful examples of the Life Tradition in Christian history is St. Francis of Assisi, who in many ways was a thirteenth-century parallel of Jesus’ life in the first century — a life characterized by solidarity with the poor, generosity, and compassion. (And, yes, Francis was part of the Crusade; like Jesus, Francis too was not perfect.) And both fascinatingly and disturbingly, Francis’ legacy was corrupted in a way that parallels the development of the Death Tradition in the wake of Jesus’ death. As Kelly Johnson explores in her powerful book The Fear of Beggars: Stewardship and Poverty in Christian Ethics,

Francis’s Testament, circulated after his death, included a strongly worded call to the friars to remain poor and lowly, never to seek protection or privileges from the church hierarchy. Meanwhile Brother Elias was constructing in Assisi a basilica in Francis’s honor. Francis’s friend Hugolino, now Pope Gregory IX, intervened to clarify the Rule and to set the conscience of the order at ease with regard to the goods they used. (59)

And so began the series of compromises that allowed future generations to believe that neither Jesus nor Francis expected others to live as radically as these original founders had lived. When the opposite was the case. Both Jesus and Francis demonstrated with their lives the power of radical love and solidarity with the poor, and called others to do the same. And I wish I had time to elaborate on even the prominent times throughout the past two millennia of Christian history in which the Life Tradition has reasserted itself — and individuals and groups have radically followed the Way of Jesus in their own time and place. But, for now, to list a few examples in name only, we see the Life Tradition strongly in the fourth century with the desert Mothers and Fathers and the early monastic communities; in the Middle Ages with Waldensians, the Beguines, and the Franciscans; and today with the New Monastic Communities such as the Simple Way in Philadelphia, Church of the Sojourners in San Francisco, Rutba House in Durham, North Carolina, and the Open Door Community in Atlanta — as well as the L’Arche Communities founded by Jean Vanier, the Catholic Worker Houses founded by Dorothy Day, and the Christian Peacemaker Teams from the Mennonite Tradition. Of course, to the world’s surprise, we have seen strong themes of the Life Tradition most recently with Jorge Mario Bergoglio, beginning with his choice of the name Pope Francis. There have been 87 Roman Catholic pontiffs since Francis of Assisi’s death and canonization as a saint. And although Pope Francis I is, for the most part, towing the party line toward women and LGBT Christians, he is also standing much more strongly in the Life Tradition of Jesus and Francis in regard to the poor than many of his papal predecessors. To quote only a few brief passages from his recent 244-page apostolic exhortation, Francis has called the growing gap between the richest 1% and the rest of us a “new tyranny”:

- The worship of the ancient golden calf (cf. Ex 32:1-35) has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose.

- It is vital that government leaders and financial leaders take heed and broaden their horizons, working to ensure that all citizens have dignified work, education and healthcare. [Sounds like John Fugelsang’s line that, “Obama is not a brown-skinned, anti-war, socialist who gives away free healthcare. You’re thinking of Jesus.”]

- Just as the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say “thou shalt not” to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills. How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?

- I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.

There are so many ways that the Jesus tradition has been manipulated, used, and abused. But Pope Francis is only the latest example on the world stage of how the “Way” of Jesus continues to be a source of wisdom, compassion, and life — of transformed life in this world through building a Beloved Community that loves the hell out of this world.

Notes

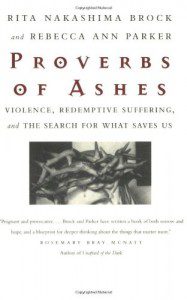

- “divine child abuse” — Rebecca Ann Parker and Rita Nakashima Brock, Proverbs of Ashes : Violence, Redemptive Suffering, and the Search for What Saves Us, 5.

- “Death Tradition” and “Life Tradition” — John Dominic Crossan, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately after the Execution of Jesus, 415, 572-3.

For Further Reading

- Rebecca Ann Parker and Rita Nakashima Brock, Proverbs of Ashes : Violence, Redemptive Suffering, and the Search for What Saves Us and Saving Paradise: How Christianity Traded Love of This World for Crucifixion and Empire.

- Marcus Borg, The Heart of Christianity: Rediscovering a Life of Faith.

- John Dominic Crossan, God and Empire: Jesus Against Rome, Then and Now.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles